Book Review

By Jay Levinson

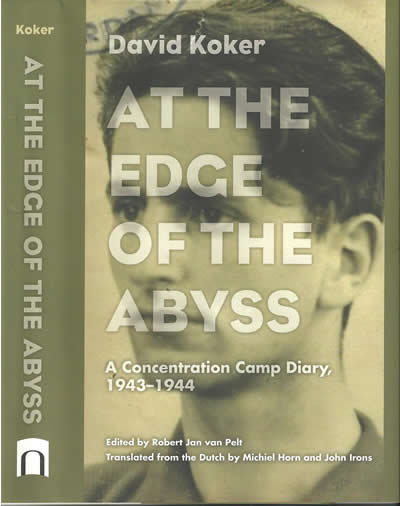

At the Edge of the Abyss: A Concentration Camp Diary, 1943-1944

by David Koke and edited by Robert Jan van Pelt

Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern

University Press (2012)

ISBN: 978-0-8101-2636-7

This

year before Passover a prominent Bnei Braq rabbi, Shmuel Markovitz

authored a booklet in which he describes at length how we must

envision Egypt as though we, too, were slaves there. He writes, for

example, "We were at the depths of denigration, totally

despairing of life." Work was the order of the day in a

pointless existence which knew no other reason than toil. Maror,

or bitter herbs, is the symbol of this feeling, but even as we taste

romaine lettuce or horseradish at the seder

it is hard for us to internalize the depravations of slavery as we

sit in the opulence and comfort of our homes.

The

diary of David Koker was written in the Vught concentration camp in

the Netherlands, and it goes a long way in describing the inner

thoughts of a prisoner who was robbed of his human identity. It is

not the Diary of Anne Frank, composed then edited in relative

tranquility while hiding. This diary contains the scrambled thoughts,

hasty notations, and inner feelings of a man who was placed in a

"reception camp." He then slowly understood the nuance of a

name change. Vught became of a "transit camp" on the way to

liquidation.

The

Nazis understood psychology very well. They instructed prisoners in

Auschwitz to write encouraging post cards, but even so word got out.

Auschwitz was a place of "Moves"

(death). It was not really just work in the East.

As

months passed Koker's possessions were confiscated, his hair was

shaven, and he was compelled to wear the striped uniform of an

inmate. His identity as an individual was taken away.

This

book is not easy to read. It is depressing. It contains jumbled

thoughts. But, it gives a true picture of the life of a slave to a

cruel master. It is "must" reading for anyone who wants to

understand the Nazi period.

Koker

experienced fleeting moments of joy, as packages from Amsterdam would

arrive, or as he would catch a glimpse of his parents, sometimes

exchanging a few words with them. The packages were eventually

stopped, and as deportations to death camps increased, he fought to

keep names off the list. Oddly enough, he developed affection for a

female prisoner, but even that natural instinct was extinguished.

Rumors

were rife as real news was withheld. Was the Eastern Front really

collapsing? Was the war about to end with a German victory, or were

the Allies about to invade? Sometimes there was hope, but usually

there was only despair.

Koker

was part of a skilled unit making communications equipment, so for

more than a year his life was spared. In the Spring 1943 the Germans

feared that the Allied invasion might come through the Netherlands,

so Vught was evacuated. Koker perished on his way to Dachau. The days

leading up to his deportation are clouded in mystery, since the last

part of the diary has been lost. Did Koker pass away on the death

train? Or awaiting reception at Dachau? We shall never know. The

secret is buried in the mass grave where Koker was interned with the

remains of more than 7600 others.

As we

read this book it is not enough to decry the cruelty of the Nazis ---

those who were rabid anti-Semites and those whom Koker describes as

"only following orders." World War II is a period that is

close to us, and most of us have heard first-hand accounts from

survivors. The stains of history are still relatively fresh. This

book, however, can serve yet another purpose. It can give us good

insight into the sufferings of the Jews in Egypt and help us

empathize with the reality of their slavery and their longing for

redemption. In that way we can uphold the challenge of understanding

the Biblical slavery from which we, too, were redeemed.

~~~~~~~

from the June 2012 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

Material and Opinions in all Jewish Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish Magazine accepts no liability for material used.

|