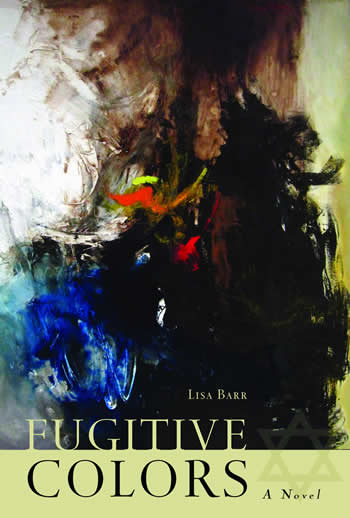

Fugitive Colors

By Lisa Barr

(an Excerpt published by Arcade Publishing, an Imprint of Skyhorse Publishing)

Prologue

Chicago, 1926

Yakov Klein slowly ran his finger over the cover of the art book he was about to steal from the library, as a burglar would a precious jewel just snatched from a glass case. Pressing the book to his face, he inhaled the familiar dusty scent of his latest prize: Gustav Klimt. It was a delicious moment, but one he would have to savor later, in the secrecy of his bedroom once the lights were out and his parents were sleeping. Right now, he had to get out of the library without getting caught.

Shoving the thick book inside his overcoat, Yakov quickly made a beeline from the art collection toward the exit, one floor down, and across the long vaulted hallway. The linoleum floor squeaked loudly as he neared the sole librarian bent over a bottom shelve next to a pile of just-returned books. He paused briefly and stared at the librarian's large buttocks straining too tightly against the cheap material of her royal blue skirt. If only he could paint her like that-compromised, determined to get the book alphabetized and in its place-but he kept walking. Thirty-two more steps until he was safely out the door.

From the corner of his eye, Yakov saw a little girl, no more than five, holding her mother's hand and watching him. He knew what she saw-what everyone saw when they looked at him-the long black wool coat, the tall black silk hat that was still too big, and the payis-long sidelocks-that Jewish custom had required him to grow his whole life. It was a uniform borne of a different century. Yakov, son of Benjamin, raised as an Orthodox Jew, wore some version of the same clothing every day-black and white, a wardrobe devoid of color or change-and he hated it.

That's why he stole the art book. If truth were told, that was why he had been stealing art books since the week after his bar mitzvah, nine months earlier. He desperately needed color. This desire was apparent at age seven when he discovered his mother's special pale pink lipstick stashed in the skinny wooden drawer in the nightstand by her bed. It was the same color as the covering for the challah on the Sabbath table. It was also the same color as the fancy napkins his mother put out on Rosh Hashanah. Yakov took the lipstick. He knew it was wrong, but he had to have it. Pink, he thought with excitement, was also the color of the forbidden pig-that un-kosher swine his father always ranted on about.

Yakov thought a lot about pigs, perhaps because he wasn't supposed to think about them. At first he felt guilty as he began to draw, but once the lipstick met the paper he could not stop until he was finished. Holding the paper to the light, Yakov felt an indescribable thrill-the plump curly-tailed treif animal was now his. He hid the drawing inside his bedroom closet. And it was on that day that he discovered the joy of art, and when the lying began.

In time, Yakov became more sophisticated in his art. Using a pencil, he drew everything around him from memory: his mother, his father, books, food, Shabbos candles-everything he'd see would soon find its way onto paper and then into the secret box hidden in his closet. No one knew. Just him and God. And that was more than enough. One day, after Yakov's father left early for the synagogue, his mother came into his bedroom, closed the door, and gestured Yakov to join her on the bed. They faced each other in silence, the kind of stern crossarmed quiet that meant he'd done something wrong. He waited.

"Yakov, I know."

She knew.

Yakov, ten years old, was his mother's only child, in a world where only children simply did not exist, unless there were problems. And there were definitely problems. Yakov would hear his mother cry at night through his bedroom wall, telling his father that she was half a woman because she could not have more children. She would go on about her sister Channa with six kids and pregnant with the seventh, and why was it God's way that she should only have one? And all the babies she lost before and after Yakov. Five, she would cry, five. At dinner, Yakov would see the disappointment unveiled in his father's eyes when he'd look at his wife across the table, and then Yakov would see his mother's fallen face. But right now, his mother, angry and sad with five dead pregnancies, knew.

"Are you going to tell him, Mama?" Yakov asked quietly. He was not scared of his father, just terrified of losing his collection of artwork.

"No," she whispered, gently wiping away a wisp of light brown hair from his forehead. Her green eyes welled up. Yakov thought, if only he could draw her like that: the loose hair falling out of her bun, her head tilted just so, her beautiful wet green eyes that were the same color as the sofa.

"I'm afraid for you, Yakov."

"Don't be," he said, sitting up straight, knowing she hated when he slouched. "I'm not afraid."

"But your father . . . and the rabbi. It is forbidden. The drawings. You need to study your Torah." His mother's tone was stern but her gaze was milky and far away. "You are too young to understand. But passion, dreams of something else, something better-can destroy." Silent, slow-moving tears began to fall lightly against her cheeks.

Are you still talking about me, Mama? Yakov wanted to ask, but knew better. Instead, he reached for his mother's trembling hand and held it tightly, protectively, inside his own.

"I won't tell him," she promised through her tears. "But you must stop. You must . . . " Her voice trailed away.

That day, his art and his lies became hers; an umbilical cord of shared but necessary silence.

What Yakov's mother did not know was that the pencil and paper were not enough. Yakov knew that only he could answer the voice nagging deep inside him: More.

More began with stolen crayons and paints from a nearby hardware store. More led Yakov to the Chicago Public Library, with its treasure trove of art books on painters, paintings, technique, and even lessons. He could not just borrow those books. That would leave a record. His father would somehow find out. At first Yakov thought that one book on Michelangelo would be enough, but it simply whet his appetite. Soon, one book became two; two became five; five turned into ten. Today's book marked eighteen-the most significant of all biblical numbers, he thought. Eighteen was chai-life.

These books give me life. Surely God understands, Yakov rationalized as he closed the heavy library door behind him.

Holding the book close to his chest, he ran the eight blocks from the library to the cheder-the dank, windowless classroom where he studied six days a week with the rabbi and other boys from his community. If only the rabbi could know that Yakov cared nothing about Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob-except to paint them. If only he could paint the sacrifice of Isaac in Abraham's hands. If only he could paint the beautiful Rachel with her long, thick, black hair and those full breasts that tempted Jacob, making him work seven years, day and night, like an ox, just to "know" her. How many times did Yakov paint that scene in his head at night, or daydream in the classroom while the rabbi droned on? If only he could paint all of his favorite biblical stories, but it was as forbidden as worshiping the Golden Calf. The images were allowed only in his head, and in his heart. His hands were bound and restrained. Painting was breathing, and Yakov was suffocating. But one day, he knew, things would be different.

Yakov told no one about the art books. He had friends, boys he grew up with, but none could be trusted not to tell the rabbi that he broke the Eighth Commandment eighteen times. Nineteen, if you counted the pig. He patted the treasured book inside his coat as he nervously opened the classroom door, knowing before he crossed the threshold exactly what was waiting for him.

"Yakov Klein, you are late again!" the rabbi shouted when he entered the room, six minutes after the other boys.

"I'm sorry." Yakov kept his gaze glued to the scratched-up wood floor.

"You're always sorry."

"I'm really not sorry," Yakov muttered under his breath.

"What?"

"Nothing."

As Yakov walked over to his desk, a leg stuck out into the aisle and tripped him on purpose. Yakov went flying, and so did Gustav Klimt. The boys laughed until they saw the rabbi bend over and pick up the stolen book, then there was dead silence. Yakov Klein, the class troublemaker, was in big trouble.

"What is this?" the rabbi demanded, his eyes blazing as he held up the book. "And where did you get it?"

Yakov knew better than to speak.

"Answer me!"

Yakov stared up at the rabbi, who was tugging angrily on his long, scraggly beard, waiting. He stole a glance at the boys around him, who were half worried for him and half thinking, better him than me.

"It's a book," he said slowly.

"Don't tell me what I already see. Tell me what I don't."

Yakov paused, long enough to muster his courage. "It's a book about art."

"It doesn't belong here!" The rabbi wagged an angry finger, the same angry finger he used whether he was discussing Commentary or Torah or doling out discipline. That finger was loaded.

Eyeing the finger, Yakov whispered, "I don't belong here, Rabbi."

"Don't belong here?" mocked the rabbi who was nearing eighty or ninety-no one knew for sure. He opened and quickly slammed shut the book on Klimt, the loud clap echoing throughout the musty room. His dark eyes behind thick glasses blazed as he wagged that finger in double-time. "Barely fourteen years old. You think you know about life, but you know nothing."

Yakov quickly glanced at the other boys, his friends. No one said a word. He saw the terror in their eyes, but suddenly, strangely, he felt none inside his own body. He took a few steps forward and stood defiantly before the rabbi. "I will show you something about life."

The rabbi's eyes widened with disbelief at his insolent student. But there was something else in those black eyes that Yakov saw immediately, which the rabbi could not conceal: curiosity. The rabbi, a teacher, a father of eight and grandfather of thirty, was only a man after all.

Yakov did not wait for a response. He quickly reached inside his desk and took out the piece of paper that he had been hiding for several months. He handed it to the rabbi. "This, I drew for you."

The rabbi took the paper and held it with both hands, first at arm's length and then up into the light. Slowly, he brought the drawing close to his face. It was a picture of the rabbi, alone, praying in his study. His large white tallis-a hand-woven shawl with thick black stripes-was draped like a cape over his shoulders, his tefillin-phylacteries-were wrapped tightly around his forehead and arm. His heavy-hooded eyes bulged not with the wrath of a dissatisfied teacher but with the joy of Morning Prayer. It was an intense, intimate moment that Yakov had captured.

The rabbi tore his gaze away from the image and stared at Yakov. Known as a man who could scold like a snake and reduce a boy to tears with a mere glare, the rabbi was, for the first time, speechless, that finger hanging limply at his side. There was well over a minyan of witnesses as the rabbi stood in silent awe of his worst student's God-given talent.

That look was all Yakov needed to confirm what he already knew: He was chosen.

~~~~~~~

from the June 2013 Edition of the

Jewish Magazine

Material and Opinions in all Jewish

Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish

Magazine accepts no liability for material used.

|