| |

2015 |

|

| Browse our

|

Don Quixote

Moses Elias Levy By Jerry Klinger

There are no photographs, no paintings, no drawings of what Moses Elias Levy looked like. He could have had one made if he wished to self-aggrandize his own memory. Levy was against that sort of vanity. He had wanted his legacy to be his epitaph. A friend described him, when he was already an elderly man of 70, as being 5'6" tall, rotund with a friendly demeanor. Two years later, he died. He was buried, a Jew in a Virginia Episcopalian farmer's private cemetery. Levy was estranged from his two sons, distant from his daughters and sister in St. Thomas. He died, not amongst his people. If there was a headstone, it has been lost to time. His extraordinary dreams, his hopes, his efforts for a safe home for his people, the Jewish people, were long lost. They were lost in the ruins of his plantation, burned by the Seminole Indians, amidst the huge tract of swamp and mixed scrub land he owned in North Central Florida. His leadership role was quickly forgotten by British Jewry struggling for emancipation. Contradictorily, he was an abolitionist, unknown among the slaves he never freed. Yet he was championed by the British Evangelical Christians who feted the Jew who hated slavery. They too forgot him… ironically …fortunately. He was quickly forgotten by everyone except for his money. Once his estate was settled, he became a footnote to his son. Levy' son, David Levy Yulee, is well remembered. Yulee is honored by the State of Florida. The son became the first United States Congressman and later Senator of Jewish heritage in American history. He was also buried in a Christian cemetery but as a Christian. Moses Elias Levy was born July 10, 1782 in Mogador, Morocco. His father was Eliahu Ha'Levi ibn Yuli a Shab as-Sultan (a court Jew) to Mohammed ben Abdallah, Sultan Sidi Muhammed III. A thousand years before Levy was born, recently converted Berber Muslim raiders crossed the narrow Straits of Gibraltar from Morocco. The Berber raiders came, as they had historically for hundreds of years, to plunder the weakening Christian Visigoth kingdom on the Peninsula. In an astonishing victory, they defeated King Roderic in 711. Recognizing weakness and opportunity, reinforcements from North Africa rushed over. Two thirds of Iberia was quickly conquered. The Emirate of Cordoba was established over time and eroded over time.

The Capitulation of Granada by F. Padilla: Muhammad XII before Ferdinand and Isabella

Moros y Cristianos For 781 years the Christians slowly retook Iberia from the Muslims. They called it the "Reconquista"2. January 2, 1492, Granada, the last Muslim Emirate, fell. The struggle to drive out the Muslim invaders is celebrated annually in Spain, Moros y Cristianos.3,4 Jews lived on the Iberian Peninsula since Roman times. Compared to life in the Christian world, they were mostly tolerated in the Muslim territories. Some Jews rose to positions of great influence as "court" advisors, physicians, merchants. Jewish life in Muslim Spain, with distinct limitations and periodic, horrific oppressions, flourished. It became known as the "Golden Age" of Spain.5 It was a "Golden Age" unknown again until the "Golden Door" of America opened to Jews centuries later.6,7 The re-conquest of Granada united Spain under one Catholic ruler. The Muslims were granted toleration in the peace treaty. Toleration for Muslims was quickly abandoned. Toleration for Jews was never a consideration. Within six months, Jews were ordered, as they had been throughout the Reconquista, to convert, leave or die. July 31, 1492 the Alhambra Decree went into effect.8 Three days later, August 3, 1492, Christopher Columbus left on his first Voyage of Discovery. Moses Elias Levy's family left for Morocco. Spanish Jews were considered by the Moroccan Sultans superior in education, ability and reliability than the native Berber Jews and Jewish tribes of the interior of Morocco. Jews had been part of Morocco since Carthaginian times. Biblical legends identify Jewish life in Morocco even earlier, to the fifth century B.C.E. Jewish missionaries reached out into the interior of Morocco and the Maghreb converting numerous Berber tribes to Judaism. Many held on to their Jewish identity well into the 12th century against Islam because of their intense warlike characters.9 By the time the Levy family found refuge in Morocco, the "Golden Age" of Jewish Morocco had long gone. Jewish life swayed between tolerant and intolerant Muslim rulers, who were generally contemptuous of Jews. Perversely, they viewed foreign Jews also as Dhimmis,10 a protected inferior People of the Book, but superior to Jews who were native. Foreign Jews, like the Levy family, were outsiders to Moroccan Jews. They were homeless and depended more upon the good will of the Sultans for their security than they could on the Moroccan Jews. The Sultans knew this and exploited the Spanish Jewish insecurity to their advantage and personal loyalty. The Levy family rose to a position of influence over the years.

Mohammed Ben Addullah Eliahu Ha'Levi ibn Yuli, Moses' father, was a Jewish advisor to Mohammed Ben Abdallah,11 Sultan Sidi Muhammad III, the governor of Marrakech. Yuli discovered a court plot by Abdallah's son to dethrone the aging monarch. He revealed the plot, saving Abdallah's life but making his own very insecure. The aged monarch would die eventually. He did in 1790. Abdallhah's successor remembered the role of the Jews and the role of Yuli in the court plot. Violent anti-Jewish riots were fermented to assuage the Arab street in the transition. Yuli recognized his life and his family's lives were in danger. As his family had done three centuries earlier to escape death, he re-crossed the Straits of Gibraltar seeking refuge, but not in Spain. He could not go to Spain because he was a Jew. The Inquisition was there.

Sha'ar Hashamayim Synagogue – Gibraltar The Yuli family found refuge on the "Rock" of British Gibraltar.12 A large Jewish exiled community of Spanish Jews had been living there for many years.13 The British had negotiated a treaty with the Sultan of Morocco in 1749 that granted Moroccan Jews the right to live on the "Rock". The first synagogue on Gibraltar was founded by Rabbi Isaac Nieto, Sha'ar Hashamayim, 1724. When the Yuli family arrived in 1790, there were three synagogues on the "Rock". Young Moses Levy, his name being Anglicized for convention, merged into the Jewish community. His education was traditional, religiously centered, following the Sephardic Minhag (custom). Jewish life on Gibraltar was not an isolated ghetto existence. Gibraltar depended for life upon international commerce. Many currents of thought and religious views filtered across Gibraltar, Protestant, Catholic, Muslim and Jewish. Cultural ideas and social ideals blended into the intellectual fabric of Gibraltar. Revolutionary ideas, emanating from France and the Americas, impacted deeply. Gibraltar is tiny. The many different peoples on the "Rock" had to find universal ways of living together in toleration and peace. It was no small wonder that one of the first Lodges of the Freemason movement was founded on Gibraltar, Lodge of St. John # 51 founded 1727.14 The first Jewish Lodge was founded on Gibraltar 1774, Hiram's Lodge #490 E.C.15 Masonry is a fraternal association of Utopian idealism centered on the brotherhood of all men. A fundamental requirement for membership is belief in a Universal Creator. No religion is singled out as correct. Masonry recognizes there are many paths to God and requires toleration of differing personal journeys to God. Being a secretive fraternal organization with private rites and rituals, conspiracy theorists abound with false, subversive, evil world domination theories about Freemasonry. Extremists have invented a mythology that Freemasonry is a cooperative effort with the Jews to worship the Devil, take over the world and crush Christianity. It is none of those things. Many prominent men were Freemasons, from George Washington to Franklin Roosevelt, Rudyard Kipling to Will Rogers to Franz Liszt.16 George Washington, the first President of the United States said described the values of Freemasonry. "Being persuaded that a just application of the principles, on which the Masonic Fraternity is founded, must be promote of private virtue and public prosperity, I shall always be happy to advance the interests of the Society, and to be considered by them as a deserving brother." 17 To succeed in the mercantile world of Gibraltar, Moses Levy needed social and economic contacts. He most likely was introduced to and became a Mason on Gibraltar.18 Masonic philosophy melded into his developing Jewish religious identity. Masonic values, though clearly not always universally applied, filled an idealistic need in the young man. He had had a personal crisis of faith on Gibraltar. Levy could not accept the absolutes of Jewish life that emanated from Rabbinic and Talmudic Judaism. Blending his Masonic Utopian ideals of universal brotherhood under God, Levy evolved his personal Jewish faith to only accept the written word of the Old Testament as the word of God. Levy's life on Gibraltar was cut short. His father died in 1800 when he was eighteen. The Levy family moved yet again, the real life epitome of wandering Jews. They moved to the Danish Caribbean Island of St. Thomas where they had "family" and economic possibility. Elias Sarquy had been the Levy family bondservant in Morocco. After the family's escape to Gibraltar, Levy's father released Sarquy from his service to the family in appreciation for all he had done to help them. Sarquy moved to St. Thomas in 1793. He quickly, and very successfully, established himself as a leading merchant in the developing Island's and Caribbean economy.19 He assisted the Levy family wherever possible. Interpersonal relationships were key to economic success in the "frontier" environment of the Caribbean. Moses Levy's Freemason connections stood him in good stead more than once. His Jewish connections and easy interchange within the interlaced Spanish/Portuguese Jewish world of the Caribbean helped also. Levy spoke fluent Spanish. The first Jew to set foot in the New World had was a Converso - Luis de Torres, a crew member of Columbus' first voyage.20 He was the interpreter for the mission. De Torres was given a simple option on the docks before Columbus left, convert and join the mission or consider a choice that would not have added very much longer to his life. De Torres was the first man Columbus sent ashore to communicate with the Indians. De Torres chose to remain behind with a small contingent of Columbus' crew when Columbus had to return to Spain. Legend says he married an Indian princess on Hispaniola. Outside of legend, de Torres vanished from history. New Christians, Conversos, were Jews who had converted to Christianity when Ferdinand and Isabella put the choices before them. Many secretly remained Jewish. Many moved to the New World to escape the reach of the Inquisition. When Brazil reverted from Dutch to Portuguese control after the fall of Recife in 1654, the previously hidden Jews chose to flee to the Islands. From Suriname on the coast of South America to the farthest reaches of the Antilles, small Jewish communities, primarily sugar, vanilla and cocoa growers, developed. Never having been accepted as citizens of any country, the Spanish/ Portuguese Jews saw themselves as part of the far flung Jewish people in exile. They called themselves the Nation. They thought of themselves as a Nation awaiting the Messiah to bring them home to Palestine. Levy traveled frequently between the various Islands, interacting with Jews and Masons, developing business connections and economic ties. He became more and more successful. Early on he established a business partnership with Philip Benjamin on St. Thomas. Philip Benjamin would take his son, Judah, born on nearby St. Croix, to the United States to live. Judah Benjamin became the Secretary of State of the Confederate States of American during the American Civil War. When he was 22, Levy married Hannah Abendanone. She was a girl from a well to do St. Thomas family. Like Levy, her family had been refugees. In 1781, the Abendanone family were merchants on a very tiny Dutch Island, St. Eustatius. They sold military and non-military supplies to the American Revolutionary forces. St. Eustatius was known as the armory of the American Revolution. British Admiral George Brydges Rodney attacked St. Eustatius to stop the illicit trade. Learning that many of the Jews on St. Eustatius had been involved in the trade and support of the Americans, Rodney singled them out for special attention. The heads of the families were rounded up and summarily banished. The wealth and possessions of the Jews was stolen for personal gain by Rodney. The magnificent synagogue on the Island was ruined. The Abendanone family resettled on St. Thomas. Rodney's personal greed and anti-Semitic animus sealed the course of the American Revolution and the inevitable defeat of General Cornwallis at Yorktown, October, 1781.21 Moses and Hannah had four children living on St. Thomas, two boys and two girls. One son, David, born 1810, would one day become the first United States Congressman and eventually Senator in American history to have been of Jewish heritage. Moses' business continued requiring extensive travel. The marriage foundered acrimoniously, ending in divorce in 1816. Levy left St. Thomas not long afterwards, never to live there again. Levy recognized economic opportunity where he could. He saw potential in Puerto-Rico and began developing his associations on the Island. It was a curious choice for a Jew to focus on Spanish Puerto Rico. The Inquisition was there. It was not as curious as it would seem at first. Jews were citizens of virtually no-where. Jewish emancipation, full Jewish legal equality, was unknown in the world outside of the United States. It was a process of gradualism, even in France which had begun the process of European Jewish emancipation and toleration during the French Revolution. Toleration and emancipation of Jews were ideas that took most of the 19th and well into the 20th century to become part of European life. Toleration and emancipation may have become State policies but anti-Semitism never was expunged from Europe. By the time Levy left for economic opportunity in Puerto Rico in 1816, Jews had been "emancipated "in France - 1791, the Batavian Republic - 1796, the Grand Duchy of Hesse - 1808, Westphalia - 1808, the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt - 1811, Mecklenburg - 1812, and Prussia - 1812. Most of Modern Europe would not emancipate Jews until the second half of the 19th century. Not even Denmark, and the Danish Island that Levy and his family had moved to, would not emancipate Jews until 1849. Jews were useful. From the Middle Ages on Jews were useful to Kings and Christian communities because they could do thing that Christians could not, such as money lending. Jews were generally kept close to the King, as property, for their exploitative, economic value to the Crown. Once that economic value had been fully extracted, Jewish expulsion was common. The Caribbean was no different. Jews had been central to the creation of the sugar, vanilla and cocoa industries. In Martinique, Jews were first welcomed because they brought industry, economy, development and settlement to Martinique. After the sugar industry was established and capable Christians had moved in to supplant the Jews, the Jewish welcome quickly ended. The Catholic Church demanded the Governor banish the Jews. The Jews had become a religious liability for the Governor and Martinique. The cycle of Jewish development, exploitation and banishment, again became another page in history. It has repeated in so many places over the centuries. Levy's going to Puerto Rico was not as curious as it first seemed. Puerto Rico was a Spanish island, isolated, underdeveloped and poorly equipped to compete in the dynamic world of the Caribbean where different European interests lay side by side, on islands just miles apart. Levy's was multi-lingual. He was fluent in Spanish. He was amicable, politically and socially adroit. He had multi-national, Caribbean wide economic connections. He had Masonic economic ties that could open doors. He had Jewish economic links. Levy's ability to cross national boundaries made an energetic, imaginative, man of his sort very useful. In Puerto-Rico, Levy astutely made friends with the Intendant – Don Alejandro Ramirez.22 Ramirez was five years older. He was a man with a New World vision not blinkered by European religious bigotry. He measured people on whom and what they were. What could they bring to the community he was struggling to develop? What their religion was, was secondary to what they could do to help him. Levy admired Ramirez and Ramirez admired Levy. Their relationship proved very successful for each other and for Puerto-Rico. Ramirez's success on Puerto-Rico was recognized in Spain. He was promoted to a more important position on Cuba. He relocated to the bigger island in the second half of 1816. Ramirez became the Supervisor of Finances of the Crown - the virtual Governor of Cuba.23 Levy joined Ramirez but with a special provision. Ramirez obtained a very unusual dispensation from the Inquisition for Levy, a Jew, to live on Cuba. Jews would generally not be permitted to live on Cuba until the 20th century and then not until after the Spanish-American War. The first Cuban synagogue was established in 1906, a Reform community, the United Hebrew Congregation.

The Levy –Ramirez association became even more successful than it had been on Puerto-Rico. Cuba benefited enormously by the economic reforms instituted by Ramirez. Even more remarkable, Levy was given permission to own land. He established a residence in Havana, purchased land, opened a sugar mill, and invested heavily. Levy prospered. He was accepted by his fellow Catholic Cuban plantation owners as an equal. Levy became a slave owner. Slavery, for Levy, was an acknowledgement of an economic and political, pragmatic reality. Slavery was biblically permitted, within limitations. It was a human, historical fact for thousands of years. Slavery was legal throughout most of the world in 1818. The last country to make slavery illegal was Mauritania, 2003. Levy saw the evils of slavery. He reviled it. As a child in Morocco, he first saw slavery. He saw Black African slavery in Morocco. He saw white Christians enslaved there as well. Morocco did not legally abolish slavery until 1922. Denmark banned the transatlantic slave trade in 1792 but permitted it in Danish colonies until 1848. The British Anti-Slavery Society was not formed until 1823. Britain outlawed slavery ten years later, 1833. In the United States, a horrific Civil War was fought, in part, to eradicate American slavery. Over 500,000 lives were lost in that conflict. Human sexual trafficking exists around the world today. Forced human labor, slavery, still exists in large parts of the "third world".24 As a Jew, Levy was painfully reminded every Passover that Jews had been slaves in Egypt. "They (the Egyptians) embittered their lives with hard work, with mortar and with bricks, and with every labor of the field: all their labors that they performed with them were with crushing harshness." Exodus, 1:14. Levy's melded Masonic – Jewish humanitarian idealism was deeply conflicted, disturbed. Levy struggled to come up with a reasoned response to slavery. Yet, he remained part of the system. Revolutionary tensions within the Spanish Caribbean and Spanish Latin America were exceptionally profitable for Levy. As a principle supplier of military goods to the Spanish army in the Caribbean, thanks to his association with Ramirez, he saw from the inside Spain's declining fortunes. He also clearly saw the rise of American fortunes. The future, his future, would be with America. A major Spanish land holding was Florida. Levy knew it was only going to be a matter of time before the Spanish need for capital, their interest in Florida, the ability to supply and defend Florida, would fail. The simplest and most logical solution for Spain was to "sell" Florida to the United States. Alejandro Ramirez, as reward for his service, was given hundreds of thousands of acres in Florida land grants. Ramirez never saw Florida. Levy purchased 53,000 acres from Ramirez, in 1819, of his vaguely identified land located in North Central, Florida, near present day Gainesville. He paid him pennies an acre. Each man thought they had done well. Eventually, Levy's land holdings in Florida would swell to more than 100,000 acres.

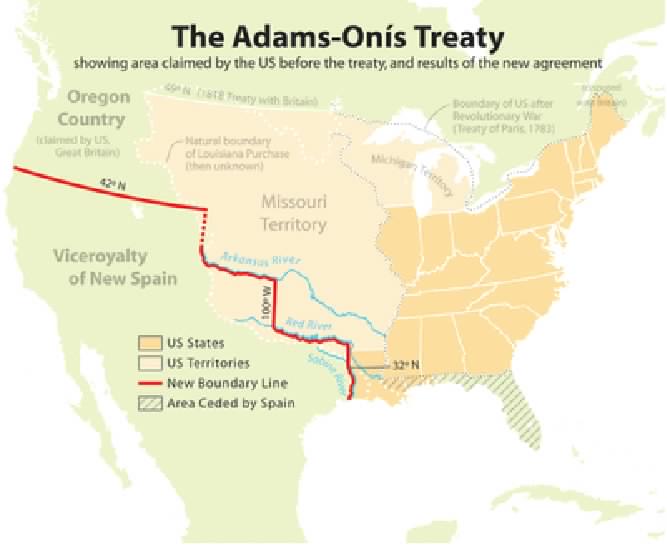

While the ink dried on the sale between Ramirez and Levy, negotiations continued between Spain and the United States to "purchase" all of Florida. Secretary of State, John Adams, successfully concluded the Adams-Onis treaty of 1819.25 The United States agreed to pay claims against Spain up to $5,000,000. The treaty defined the Mexican border along the Sabine River. The treaty ended, or so it was thought, the long standing southern border dispute with Spain. Florida was a minor concern for Spain compared to the vast, rich American Southwest. Spain did not have the resources to defend Florida after the devastation of the Napoleonic wars. Spain could not control Florida's Seminole Indians or Florida being used as a haven for runaway slaves from the United States. Seminole Indians had been bloodily raiding the Georgia frontier from East Florida for years. 1817-1818, after the First Seminole War, East Florida had been invaded and effectively held by the American military under General Andrew Jackson. The United States Senate ratified the treaty Adams Onis Treaty in 1821. Any person living within Florida when the United States took possession became American citizens. That is everybody except Indians and slaves. Levy timed his arrival in Florida to coincide with the effective date of the treaty to become an American citizen. To his dismay, his boat was becalmed, within sight of land. Levy physically set foot on Florida a few days after the transfer from Spain. For years, until it was legally settled, Levy's enemies challenged his and his sons' citizenships. The argument turned on intent vs. what actually happened. Intent vs. actual became a metaphor for the balance of Levy's life as an American citizen. The key to the future and fortune was America, people and dreams. Why not for Jews too, he reasoned? America was different. Levy, like Jews since the beginning of the Diaspora, knew a return to Palestine would have to wait for the Messiah. America was the New Jerusalem. Levy was a good businessman. It was obvious to him that American ownership of Florida would multiply Florida land values. Though under-populated, Florida would prosper with proper development. Levy was 39 years when he left Cuba for Florida. He was a very wealthy man. He had prestige, respect and connections. He was divorced. He lived a life apart from his family, pretty much rootless. It is not often in an individual's life, certainly not at only 39 years of age, that a person is free to evaluate their life, to think in terms of dreams beyond just the self. That is exactly what Levy did. Levy saw and lived the Jewish condition for years, from many different physical, religious, and social vantages. Homelessness, theistic atrophy, anti-Semitism, ignorance, isolation from modern life, narrowness of opportunity and educational skills, the inability to defend themselves, were all parts of the Jewish tapestry that Levy brooded over. Levy was not the first and certainly not the last to wonder what he could do to help his people. Money gave him the luxury of contemplation. Masonic/Jewish ideals of service to his fellow man filled his soul. Levy's life was said to be consistent with the Judaic principles of Tikkun Olam, repairing the world, preparing the way for the Messianic era by good acts encompassing all of humanity and nature. Tikkun Olam, before 1950, after which the concept for Jews evolved into universalism, was more personal, individually, spiritually redemptive. Repair of the world, in Levy's time, preparing it for the Messianic era, was more Masonic than Jewish. Levy could have remained contemplative, perhaps written a book. He was too energetic a man to be sedentary. He was an activist. He put, not just his money, but himself into where and what he believed. It obviously was very successful in business. Why not in a new life for the Jewish people, he reasoned? Years later, Levy wrote about his life decision. "When I acquired money, Levy recalled, I might have collected my children, perhaps (re)married & have followed in the same footsteps of my fellow debased people – eat fat turkies, drink good wines, keep a carriage, be lofty & arrogant, get husbands for my daughters who will do the same &c. To follow such a direction would have been most wretched, debased & wicked." 26 Spending the rest of his life focused on himself would be an empty, selfish epitaph. He was not looking for self-aggrandizement. He was not looking for immortality. Levy wanted to live a "Godly Life" as the Rabbis of his youth and the Evangelical Christians he later came into contact with put it. A fire burned inside him. He could not save the world, he could, perhaps, help save the Jews from the world and from themselves. A reflective Evangelical guilt built up in Levy as his fortunes grew while living in the Caribbean.27 The purchase of the Florida lands from Ramirez permitted Levy to do two things simultaneously. Florida and America would permit Levy to put his ideals into real action. He could do more than talk about a better world for Jews; he could do something about it. Florida land development would also multiply his personal wealth, if he were successful. Doing good did not mean self-impoverishment. Levy enjoyed what creature comforts his wealth brought him. He savored the influence and good his wealth enabled him to do. Levy thought long and hard about his new land in Florida. Wide spread Anti-Semitism in Europe, especially in Germany and Russia, was becoming virulent. He visited his son Elias and his daughters Rahma and Rachel in 1816, being educated in England. He was dismayed and disgusted. Elias attended a Jewish led school that measured financial success as an affirmation of success in life. His daughters attended a non-Jewish school in Brighton. They had to assume non-Jewish names to avoid the anti-Semitism. Levy chose to educate his son David in the United States instead. He asked a friend, Moses Myers to look after the boy. David was sent to a Unitarian school, with Levy's consent, where he would be educated and imbued with humanitarian values. At the Unitarian school, David was neither given a Christian or Jewish education. David's lack of a Jewish foundation would have disastrous consequences later. "In Paris Levy observed that secular-looking Jews were often evicted from their homes after their religious identity was revealed to the landlord. On the city streets he spent time in discussions with poor Jewish peddlers. If these men acquired a trade, as many of them did after Napoleon awarded them citizenship, they were compelled to work on Saturdays and were shunned by their Christian co-workers, most of whom would never condescend to speak to them. Rather than break the Sabbath and endure social ostracism, a meager peddler's life appeared to be the only option left for them."28 The experience did little to assuage Levy's personal dark misgivings about a Jew's future in a Gentile world. The Florida land purchased changed Levy's ideas to practical application. Levy envisioned a safe haven, a colony of refuge for his oppressed brethren in Europe. There were many practical problems. The land was raw, unsettled, undeveloped. European Jews had little experience as farmers, little less with plantation life and sugar planting. They may have been well trained in Talmud and Rabbinic Judaism but they were poorly trained in contemporary science, culture and economics or even animal husbandry. They had little knowledge of or training in self-defense, a very necessary skill on the frontier. His colony, by necessity, would have to teach Jews how to live in the world outside of Rabbinic/Talmudic Judaism. Educating the Jewish immigrants was very important. Levy became a champion of liberal American Jewish education. Levy's focus on education for the Jews, lead to his belief in universal, free public education. In Florida, he became a charter member of the Florida Education Society.29 Levy believed education included education for emancipated slaves. How to get the Jews to come to his safe haven for them in Florida? Without question Levy understood he had to invest his personal fortune into the colony. He needed to make basic capital improvements, housing, land development, roads,30 buildings, sugar processing equipment, etc. Moving from the frying pan to the fire of the raw frontier, facing privations, Indians, malarial swamps, unknowns, was not enough to attract Jews. They were not returning to the Holy Land. They were not Halutzim. They were being asked to come to a new, new land. The Jews had to be sold on coming. Levy had made the acquaintance of a young man, Frederick Warburg, while on his commercial trip to London in 1816. He shared with him his dream of a Jewish home in America. The idea appealed to Warburg. When Levy tried presenting the idea to the French Jews in 1816, they were far from receptive. Years later, Levy engaged Warburg to market his colony to the Jews when he began to implement his dream.

Beginning in 1822, Levy plotted out, cleared and began development of his sugar plantation- Jewish colony two miles north of Micanopy, Florida. Named after a Seminole Chief, Micanopy was little more than a collection of huts in the sparsely populated lands poorly located for general agriculture. Micanopy was far from anywhere. By 1825, the Levy Plantation Levy encompassed 2,000 acres. He named it Pilgrimage Plantation. It was far from prosperous. Pilgrimage operated like a modern Israeli Moshav – communal labor, private ownership. Some lands were set aside for private development for each Jewish family. Between the slaves and the Jewish settlers, the Plantation operated communally. It is not known if Levy's ideas of modern Jewish education and Jewish communal rearing of children were implemented. Levy had invested most of his monies in the project with little to show for it. His capital running dangerously low and the entire operation facing economic implosion, Levy went to London to raise more funds. Immediately in London, Levy set to work promoting his Colony to Jews. Eventually he was placing advertisements in the European press promoting his Colony. Levy appealed to Jewish financiers and leaders. In a characteristic letter framed with Jewish duty, obligation, responsibility and guilt he wrote to Goldsmid:31 "I call on you as a religious Person… for in helping the fallen house of Israel (you are) really and truly assisting the human race at large." 32 Wherever he could he used his status as a wealthy, successful Jew from the Caribbean to project himself into British Jewish society, make connections and to become actively involved in Jewish interests. It was not the first time he interjected himself as the outside arbitrator of Jewish internal concerns. In Curacao, 1809, he became involved in the schism of the Jewish community that erupted over the pronunciation of Hageffen or Hagaffen by the Cantor over the blessing of wine. Levy was asked to intermediate by the Jews and the totally baffled, frustrated Dutch Governor of Curacao. Superficially, the schism within the synagogue community was over trifling matters. The actual struggle was for power, control, influence and change between Ashkenazic and Sephardic traditions. Jews have a long history of near physical violence when Ashkenazim and Sephardim clash over religious ritual. In the Caribbean, the St. Eustatius Dutch Governor threatened to expel the Jews from the Island unless their infighting would end. The British Governor of Colonial Georgia threatened to bring out the militia to put down the Jewish infighting. Levy was beyond frustrated with the Jews in Curacao. The community split with multiple synagogues reflecting different traditions. Tensions remained wherever Ashkenazim and Sephardim butted heads in the Caribbean and elsewhere. Marriage between the two communities was considered worse than marrying a Christian. In London, Levy promptly interjected himself into a seething struggle. The struggle was for Jewish emancipation. Within a matter of months, Levy, the outsider, could move between the Jewish warring groups. He moved easily between Jews who feared rocking the boat and Jews who wanted to rock the boat to gain what they believed were their rights as British Jews. Both sides were bitterly at odds. Levy was an outside activist. He became an outside "agitator". He did what had never been done before. He injected himself into the nascent British Jewish emancipation movement as a public advocate. He spoke to large audiences, he wrote letters to newspapers. Within months, Levy the outsider, was a leader of the Jewish emancipation struggle. Levy naturally sought out allies. He was used to interacting with the Christian community. Recognizing a confluence of interests between the emerging Evangelical communities, liberal British Christian Philo-Semitic supporters of Jewish emancipation and his own deep personal animus to slavery, Levy acted. Levy did something that was not traditionally done in Jewish – Christian relations, he again went public. He reached across the aisle to Christians. Jews historically tried to keep low profiles. They feared creating situations that might endanger their quasi-tolerant host countries or their status in those countries. They preferred to work invisibly behind the scenes. They certainly did not reach out to Christians as equals. Levy did. He was the first Jew to publically speak against slavery before crowds that grew to thousands of Christians and Jews together. He wrote letters to the newspapers. He openly forged links with the British abolitionist movement. He shocked and frightened conservative, establishment Jews who feared interjecting themselves into British politics. They especially dreaded any involvement in controversial politics with Christian Fundamentalists. The driving forces behind the newly created British Anti-Slavery Society (1823) were Evangelicals. Levy's Jewish identity and his Masonic background were not threatened by Evangelicals. Levy; on the one hand saw an opportunity to publically speak out as a Jew against slavery. On the other hand, he understood the British would see Jews standing up for human rights, even slave rights. Jewish rights would also become the issue. Early in 1828, after three years in Britain, Levy wrote and published a very dangerous tract for an American Southern Slave Planter. He knew he risked his fortune, possibly even his life, with the pamphlet that would be considered seditious in the American South. Levy published, anonymously, his solution to solving the Slave problem, A Plan for the Abolition of Slavery.33 In some ways, Levy's plan was radical, as were other of his non-conventional ideas about Jewish life on his Colony in Florida. In other aspects, his ideas were not original or even radically original. What was original and very, very radical was that they were proposed by a Jewish- American Plantation, slave owner who abhorred slavery. It had never been done before. Levy called for the gradual abolition of slavery. The idea was not new. It had been proposed by many idealists before him. He proposed that the children of slave "marriages" would not be inheritable property but free. Black children should be communally raised and educated. Free men needed education to live as free men. It was an idea that flowed fluidly from his rejection of Rabbinic/Talmudic education for Jews at Pilgrimage Plantation. To ameliorate what he saw as the inherent racial animus created by the slave system, between whites and blacks, miscegenation was the logical solution. He was not the first to think of mixed marriages as solutions. Black and white marriage was not that unusual in the Caribbean and even in the Southern American Society, though not as common. It was quite common in Cuba where Levy had first been involved in slavery. He felt that the best racial characteristics of both Whites and Blacks, mixed together, brought out the best and ameliorated the worst in each through the children. A Plan for the Abolition of Slavery, answered the midnight imaginations of slave holders reaching for their guns at every bump in the dark fearing a slave insurrection. Violent, bloody, slave revolts were very real in slave holder's thinking. Twenty years earlier, drenched in blood, the slaves of Haiti rose and defeated the Whites and an army sent by Napoleon. One half of the Caribbean Island of Hispaniola, the Black half, won their independence in 1804. The other half of the same Island remained slave under the Spanish. Levy recognized, gradual abolition of slavery, by natural attrition, was not fair. It was not fair that slaves should remain slaves and their children should be free. It was unfair and fair for Levy and many other abolitionists. It was the price to avoid bloodshed. It was the price of peace. Levy's finances in the United States continued to deteriorate. He had to return. The British Jewish emancipation movement, that he been a leader of, collapsed a few years after his departure. The British anti-slave movement did not need the novelty of a Jew speaking for it. It continued successfully without Levy. Fortunately for Levy, no one in the United States, certainly among the Southern Planters class, realized that Levy, though considered eccentric, was the author of A Plan for the Abolition of Slavery. Returning to Pilgrimage, Levy had been unsuccessful in attracting a single new investor to help with his dream. The Jewish population at Pilgrimage was about 21 souls, men, women and children. Not enough even for a minyan. Levy knew his Jewish colony ideal was a failure. He did what he had to. The colony, his plantation, his lands were opened to anyone who would be willing to come and settle. Pilgrimage Plantation limped on for the next seven years, slowly, painfully developing. It ended violently one day in 1835. The Plantation was destroyed, burned to the ground during the Second Seminole War. Levy found shelter in St. Augustine, Fl. Many of the settlers retreated to Micanopy. The bloody Indian war ended Levy's dreams. He was financially crushed. To compound his problems, his investors sued for their money. Title to his land was clouded by the impreciseness of his Spanish land grants. He could not sell a single acre of land to pay his bills or for funds to live on until the title was cleared. It would take years of expensive litigation. Levy was 53 years old. He was impoverished. He subsisted on $14 a month, selling what little possessions he could to pay his legal fees. Fourteen long years of court fighting by his attorney George R. Fairbanks, would go by before Levy's titles were cleared. He sold some of his property in 1849, paid his debts and had sufficient funds to live the life of a Planter gentleman again. The freeing of his lands again made Levy one of the wealthiest people in Florida. His extensive holding had appreciated significantly as Florida developed. He was 67 years old. His health had been compromised. Levy lived his life pretty much separated from the Jewish community though he did maintain an active corresponding relationship with prominent American Jews. He never did remarry. Like many Americans, he was caught up in the Messianic expectations of the 1840's. The Messiah did not arrive. Levy delved into non-Jewish mysticism seeking answers that never came. He did not turn to his own Jewish faith for answers. Levy picked and chose what he believed in and what he did not. He tried very hard to observe the peace of the Sabbath and abstained from eating pork. He clearly ignored the Jewish laws re: slavery. It is expressly forbidden to sell slaves to non-Jews. Desperate for funds, he did what he did. David Levy, Moses' youngest son and his father had always been at odds. He was a troublesome, even rebellious child. David did not go to college as his father had wished. He returned to work on Pilgrimage Plantation instead. After the destruction of Pilgrimage Plantation, David went to St. Augustine to study and practice law.

David Levy Yulee Ruins of Yulee sugar Plantation David Levy entered Florida politics and was elected the Florida territorial representative to the United States House of Representatives in 1841. He spent four years in the House working for Florida's admission to the Union as a State and for the expansion of slavery. Florida was admitted to the Union as a State in 1845. Levy was elected to the United States Senate. He was the first Jew in American history to be elected to the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. Levy, more than once had to defend his Jewish heritage when confronted by blatant anti-Semitic derision on the floors of the House and the Senate. A year later, in 1846, Levy controversially changed his name from Levy to his less Jewish sounding family name of Yulee. He married a devout Presbyterian, Nancy Christian Wickliffe, the daughter of the former governor of Kentucky, Charles A. Wickliffe. David and his brother Elias had been estranged from their father for many years. A condition of marriage of Nancy Wickliffe's was that David and his father must reconcile. The animosity rankled her Christian sensibilities that a father and son should be apart. It was a bitter pill for Levy. Years earlier Moses had written, "Every Jew who contributes knowingly to the …amalgamation of the house of Israel is an enemy to his nation, to his religion, and consequently, to the world at large."34 Moses Levy blinked. Levy somewhat reconciled, a formal but not cordial relationship with David ensued. David and Nancy were Church wed. Elias followed his younger brother and changed his name to Yulee as well. Moses never forgot. The two brothers were included in Moses' will but were left only $100 each. Levy named executors of his will men who were bitter political enemies of David Yulee. He left the bulk of his significant estate to be split between his two daughters and his sister in St. Thomas. The sons sued. Years of bitter, expensive litigation was fought for the money. In the end, the estate was settled out of court. The money was divided five ways. Levy was determined to be of unsound mind when the will was written. Senator David Yulee was crowned the "Florida Fire Eater" for his pro-Slavery and pro-Southern views. After the Civil War, David Yulee became a major railroad developer in Florida. David Levy Yulee is an honored son of Florida today. A County, a town, streets are named in his honor, Levy County and the town of Yulee. His sugar plantation, near Homosassa, is a Florida historic site.

David Yulee died in New York, (1886). He was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, Washington, D.C., next to his wife Nancy, as a Christian. As became his custom, Levy traveled in the summer of 1854, to the cooler summer resort of Greenbrier, in the hills of western Virginia. Many Southern aristocratic planters vacationed there regularly. There was a spa in Greenbrier. The waters were said to have remarkable rehabilitative effect. Levy died quietly September 7, 1854 at Greenbrier, despite the curative effects of the water. His Christian Planter friends buried him, a Jew in a local Episcopalian farmer's family cemetery. If there was a headstone, it has been lost to time. His epitaph was his life and that was largely unknown, eclipsed by his famous son, David. Pilgrimage Plantation has been reclaimed by nature. Even the developed sites that were burned out are gone. The Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, in coordination with the town of Micanopy and local community support, is engaged in placing a Florida State Historic interpretive roadside marker in Micanopy in Moses Elias Levy's honor. It has been two hundred years since Levy wanted, tried and failed to create a safe haven for European Jews in America. He wanted them to come, to escape deadly European anti-Semitism. Ironically, today, two centuries later, once again calls are going out to European Jewry, from the United States and Israel. Each of those lands is calling on Jews to escape deadly, resurgent European anti-Semitism.

Jerry Klinger is President of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation www.JASHP.org Jashp1@msn.com

1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RfHnzYEHAow 2 http://www.spanish-fiestas.com/history/reconquest/ 3 http://www.festesdelcampello.es/ 4 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moros_y_cristianos 5 http://www.sephardicstudies.org/islam.html

6 http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6359435 7 Emma Lazarus coined the term, "Golden Door" in her poem, the New Colossus. The poem is affixed to the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor. Lazarus was a descendent of Spanish Jews and an ardent supporter of Zionism. 8 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alhambra_Decree 9 http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/Morocco.html 10 http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/anti-semitism/Jews_in_Arab_lands_%28gen%29.html 11 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohammed_ben_Abdallah 12 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Gibraltar 13 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_Gibraltar 14 http://inhabitants153.com/A%20short%20history%20of%20Freemasonry%20in%20Gibraltar.htm 15 http://inhabitants153.com/Hiram%27s%20Lodge%20No.490.htm 16 http://famousmasons.com/masons/ 17 http://www.themasonictrowel.com/masonic_talk/stb/stbs/32-02.htm 18 Levy lived on St. Thomas from 1800-1817. The second Masonic Lodge on St. Thomas was a Jewish Lodge, founded October, 19, 1818, Harmonic Lodge # 356 E.C. It was not recognized by the Danish Governor until 1819. Jews were not welcome in the Island's existing Danish Freemason Lodge. Harmonic Lodge was established to accommodate the Jewish community and the Free Black community. (Grand Master John Woods – St. Thomas Harmonic Lodge -Thank you for your inquiry. I can send you some information on Harmonic Lodge No. 356 EC, but it is likely that you would have to find out about membership in the 19th century through England. Harmonic Lodge, as its name implies, was started by Isaac Lindo, a Sephardic Jew, to accommodate local Jews and "Free Colored" that were not allowed to join the local Danish Lodge. The first Master, Samuel Hoheb, and many of the succeeding Masters, were Jewish. The Lodge was founded in October 19, 1818.)

It is not probable that Levy may have become a Freemason on St. Thomas for two reasons. First, given his frequent travels away from St. Thomas, he would not have had enough time to become a Mason. Ritual initiation requirements are time intensive and consuming. A second reason he may not have become a Mason on St. Thomas was confirmed by Peter Aitkenhead, the assistant librarian of the Museum of Freemasonry in England, who was asked to research Levy's possible membership. "I regret to say that we have not been successful in tracing the name of Moses Elias Levy in the membership lists of the Harmonic Lodge (now) No. 356. There were no other English Constitution Lodges meeting in St. Thomas at that time."

Levy used his Masonic connections with the Dutch Governor of Curacao to help mediate a Jewish community schism on the Island in 1819. The schism centered on an inability of Sephardic and Ashkenazic Jews to coexist. It was frustratingly reprehensible and incomprehensible to Levy that Jews with different minhagim (customs) could not find a way to live together. Ashkenazic – Sephardic conflicts became so acrimonious that Christian governors in Curacao, Colonial Georgia and St. Eustatius threatened militia action to keep the Jews from inflicting bloodshed on each other. 19 Through the Sands of Time, A History of the Jewish Community of St. Thomas, U.S.Virgin Islands, Judah Cohen, Brandeis University Press, 2004, Hanover, London/ 20 http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/Marranos.html 21 http://www.jewish-american-society-for-historic-preservation.org/images/Golden_Rock_to_Golden_Door_-3a.pdf 22 http://www.encaribe.org/es/article/alejandro-ramirez-blanco 23 http://www.ecured.cu/index.php/Alejandro_Ram%C3%ADrez 24 http://www.endcrowd.com/human-trafficking-facts-and-statistics/?gclid=CjwKEAiAx4anBRDz6JLYjMDxoQYSJAA4loRmnLFGv404iH6-aJATx-MRRVQfDPrJgt492LwR-OxKXRoCQt7w_wcB 25 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adams%E2%80%93On%C3%ADs_Treaty 26 Levy to Henriques, 1 September 1853, box 40 Yulee papers, cited in Moses Levy of Florida, by Chris Monaco, LSU Press, 2005, pg. 40. 27 He was becoming what he despised, "a mere money-making animal." Monaco, pg. 39, M.E. Levy to the editor, World (London), June 1828. 28 Op cit, Monaco, pg. 46. 29 Thomas E. Cochran, History of Public Education in Florida, Lancaster State, Dept. of Ed. Bulletin, 1921 #1.1

30 Levy, in a joint venture with the New York Florida Land association, improved upon an Indian trail making it wagon passable from his Plantation and the town of Micanopy to the St. John's River. 31 http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/6765-goldsmid 32 Letter from Levy to Isaac Goldsmid, Nov. 25, 1825, cited in Jewish Life in Florida, MOSAIC, A Documentary Exhibt from 1763 to the Present, Green and Zerivitz, 1991, Jewish Museum of Florida, Miami Beach, Fl. 33 Dr. Chris Monaco rediscovered the long lost anonymous tract in the 1990's. He identified Levy as the author and republished the tract as a book in 1999, under Wacahoota Press, Micanopy, Fl. 34 Monaco, Moses Levy of Florida, page 50

from the 2015 Editions of the Jewish Magazine Material and Opinions in all Jewish Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish Magazine accepts no liability for material used. |

|

| All opinions expressed in all Jewish Magazine articles are those of the authors. The author accepts responsible for all copyright infrigments. |