|

Lachish

by Jacqueline Schaalje

Forty kilometers south of Jerusalem, Lachish almost disappears into the fertile hills of the Sh'phelah, (land area along the sea coast) but once on top of the tel one gets a magnificent view to Bet Guvrin in the north and the Hebron hills in the east. This strategic stronghold ended its formal history in the second century BCE, when all occupation of the site ended. Long before that, Lachish experienced its famous siege by the Assyrians.

Lachish's earliest history begins with the Canaanites who lived on the tel since the fourth millennium BCE, under their own city-kings. They built one of the mightiest cities in the south of Israel, surrounded by a wall and a ramp, with a moat at its foot. It was the seat of the Egyptian governor who oversaw southern Canaan, as becomes clear from the Egyptian Amarna letters dating to the 14th century BCE.

The Bible describes how Lachish was subsequently conquered by the Israelite warrior-ruler Joshua (Joshua 10:1-32), who had already pacified nearby Gibeon, which had become friendly with the Israelites. In order to ward off the foreign danger, the Amorite king of Jerusalem, Adonizedek, suggested to four other Canaanite rulers in Judea to enter upon a pact. Among these was the king of Lachish, Japhia. The kings consented. The five first marched with their armies to Gibeon and besieged it.

The Gibeonites, worried, dispatched a message to the army camp of Joshua in Gilgal, with a plea to come to their rescue. Joshua answered them, and with the help of G-d, who amongst other feats threw big hailstones upon the enemy that instantly killed them, victory over the Amorites was inevitable. After slaughtering every one of them, Joshua returned to Gilgal.

The five Amorite kings alone had escaped the ambush, and hid in a cave near Makkedah. When Joshua found out about this he ordered his men to roll large boulders in front of the entrance. Afterwards, they were executed. After a daylong exposure of their corpses on poles, they were thrown back into the cave where they had hid, and there they still remain to the present day - or so the story goes.

Immediately following Joshua embarked upon an admirable display of superior military power. On the second day he overcame Lachish and when the king of Gezer, Horam, came to Lachish' assistance, their army was defeated too. After that, Joshua became unstoppable. In reality his conquering and slaying of "Kadesh-Barnea till Gaza, and the whole land from Goshen to Gibeon (Joshua 10:41)" probably took much longer or was less complete. An alternate theory says that Lachish was destroyed by the Philistines.

The defeat of the large Canaanite city by the then still primitive Israelites may sound somewhat overboard, were it not for the archaeological discovery that Lachish was not surrounded by a wall at the time of the conquest, 1200 BCE, and that a destruction did really take place. The Israelites did not inhabit their new prize-city at first. Only in later centuries king Rehobeam of Judah did just that. He built a city wall to protect it against the Philistine enemy and a palace-fort (II Chronicles 11:5-11).

Israelite palace at Lachish

In later generations, Lachish became more important, maybe the second most important city in Judah after Jerusalem. King Amaziah fled there when a rebellion broke out in Jerusalem (II Kings 14:19), but his pursuers found him and killed him.

In 760 BCE there was an earthquake, after which the city partly had to be rebuilt (Amos 1:1, Zachary 14:5).

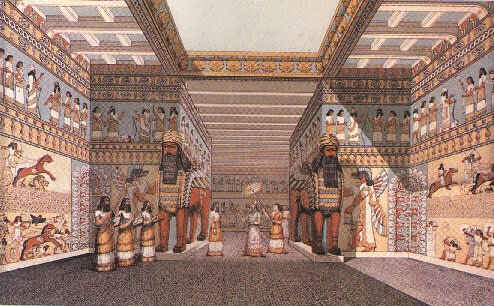

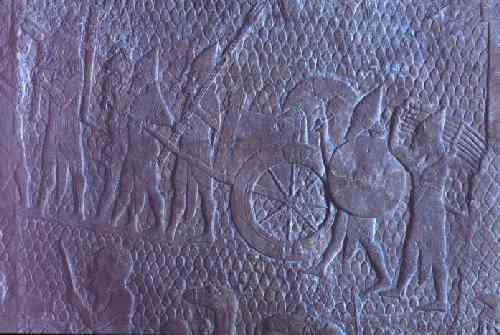

The next important event was the Assyrian invasion of Judah in 701 BCE, which is also described in the Bible. Their emperor Sennacherib was keen to conquer Lachish. How important the city was for his strategic purposes, is shown by the carved reliefs that were made of the siege and ensuing battle, that were installed in the central room of his new palace in the Assyrian capital of Nineveh. They were discovered in the 19th century when excavations in Nineveh first opened and several palaces of the sumptuous culture of the Assyrians appeared. The reliefs are remarkably detailed and realistic. They show a developed war-machinery on the part of the Assyrians. Upon a ramp that they had built to facilitate the siege, the Assyrian soldiers approach the city walls in neat orders of archers, flanked by infantry, who in their turn defend carts which were used to pound the walls. Supplies were carried by camels. On the bulwarks and towers were the defenders: archers and slingers of stones.

Interior of Sennacherib's palace in Nineveh

After the walls breached, there ensued a terrific fray of flying stones and constructions, which is also portrayed on the battle reliefs. The Assyrians set the city on fire (in some place the archaeologists found 50 centimetres of ashes). Many inhabitants were exiled to Assyria to become slaves and servants. In the Nineveh relief, whole families are carried off, their goods looted; men are tortured and the Judean governor is seen kneeling for Sennacherib. Many people also died in the battle, as is witnessed by a mass grave which was later found by archaeologists, with 1500 human skeletons, mainly of women and children, mixed with pottery from the year 701 BCE.

relief from invasion of Lachis

After their Judean campaign, the Assyrians did not live in Lachish, but gave it and the other conquered cities in Judah to divide between the Philistine kings of Ashdod, Ekron and Gaza.

relief from invasion of Lachish

But apparently some Jewish inhabitants must have come back, because later the city was again in Jewish hands. From the next siege, this time by the Babylonians in 587 BCE, eighteen Hebrew ostraca (pottery shards) were recovered. They are now known as the Lachish letters.

One of these has a moving message; it was sent from a Judean outpost to the city of Lachish, in warning of the impending Babylonian destruction. It reads: "Let my lord know that we are watching over the beacon of Lachish, according to the signals which my lord gave, for Azekah is not seen." Lachish and Azekah were the last two Judean cities before the conquest of Jerusalem in the same year, says the prophet Jeremiah (Jer. 34:7). This pottery inscription is now in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

After the exile in Babylon, Jews returned to Lachish (Nehemia 11:30). A Persian governor lived in a new residence which was built in the place of the Israelite palace-fort. After the Hellenistic period occupation suddenly ceased.

Visit

The actual visit to Lachish is somewhat less exciting compared to the stories and legends about it. The site has been last excavated in the eighties, and as it has not been turned into a national park, it is rather overgrown; helpful signs or explanations are absent.

To reach Lachish: take the Bet Shemesh road south in the direction of Kiryat Gat. Turn south onto route 3415 till reaching the parking lot.

From the parking lot up there are some loose stones. These belonged to the Assyrian siege ramp. The fierceness of the battle is attested to by the thousands of slingstones and iron arrowheads that were found in this area. The access road is the Israelite entrance road leading to the city's gate. The road was ingeniously built to ward off intruders, as the shield was carried on the left arm, so the right side was exposed to attacks from the city's defenders on the wall.

If the city wall is followed north, one can look into the Canaanite moat; here there stood an ancient temple, from which cult vessels and imported Egyptian artefacts were extracted.

Back up the slope there are remains of the Israelite outer and inner walls (there was a double wall); they can also be seen in the Assyrian reliefs. There were also an outer and inner gate. The outer gate was through a huge tower. The inner gate consisted of three pairs of chambers, and is the largest ancient gatehouse known in Israel. Although the outer, western wall of the inner gatehouse was brought down by Sennacherib's battering rams, it was reconstructed by archaeologists; the cement line indicates the restorations.

The returning Jews after the exile also rebuilt the outer gate, although they left the inner destroyed gate as it was. The ostraca with the famous inscription was found in the new outer gate guardroom, which since has also been restored.

relief from invasion of Lachis

Right behind the gate is the palace area. It was built on a huge platform, which is still seen. It was built in stages and further extended. Next to the palace were storehouses and stables. The first set-up was by king Rehoboam, who built a square platform. This is excavated, but an older, underlying Canaanite temple that used to have a cedar roof, painted walls and - still visible - stone steps, cuts through the square. A successor king extended the palace to the south. Later it was extended even more to the north and east. The remaining Israelite ruins were cleared for the Persian residence that was built on the same platform; the two columns and a door-sill remain of this. In the space between the palace and the western city wall houses of the Israelite period were dug out.

In the city itself, there is a sacred area in the middle towards the east wall, dated to the Israelite period. It consists of a small room with a low bench. In the western corner there was a raised altar, dating from the time of king Rehoboam (10th century BCE). Later it was covered by a terrace. On top of it came a second century BCE temple, which uses the basic plan of the Israelite temple, but with a courtyard and two rooms. It is not clear whether this temple was used for Jewish worship.

Further to the south, there is an overgrown ruin which could also have been an ancient temple. Also there is a deep square shaft in the city. It has been suggested that it was used as a water system or alternatively as a quarry. The precise knowledge of this will be left to later explorations.

~~~~~~~

from the June 2002 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|