|

The Influence of Ahad Ha-Am on modern Israel

By Sidney Rosenfarb

During the time of the beginning of Zionism, which was at the end of the 1800's and beginning of the 1900's, the Jews were drawn in many directions. There was the Yiddish culture advocates, who while they had no external religious expressions of their Jewishness, yet felt that as Jews, they possessed a culture far superior to that of the native culture in the lands in which they lived. To this group, the procreation and enjoyment of the Yiddish culture defined a national entity of the Jews.

Opposite of this view were the political groups of the many and various venues of thought. Amongst them were the Bolsheviks, the communists, the Socialists etc, all divided up in their many sub-categories. These Jews believed that the future of the Jew was to be found in a stable government which gave equality to all of its citizens. They had no religious leanings, but felt that the Jews, both as a group, and as individuals, had their future tied up with the form of government that could grant them their personal liberties.

The religious Jews, in their various forms, Chassidic or just traditional, were losing numbers to the various ideologies that were stirred in the winds. The leading Rabbis in most cities warned their faithful to separate from the Yiddishists, Zionists, and Socialists (in all of their various forms).

The Zionist movement was just beginning to sprout its head. It was small and unorganized. The various Zionist groups were local with out the international organization that was to come later. The draw of the East European Jew to Zion was like a magnet, like a dream. The conditions under which the Jew lived in Eastern Europe were terrible: Pogroms, discrimination and material hardship, coupled with the possibility of oppressive forced military service, Zion was more than a dream, it seemed an only choice to many. To live in our own land, to determine our own fate drew many youth to desire that this be the logical possibility.

Unfortunately, Herzl had not yet set up his Zionist congress, nor revealed his dream. Life in Israel was wrought with danger from Arabs and disease. The land needed hard work and living conditions were very trying even to the most dedicated Zionist.

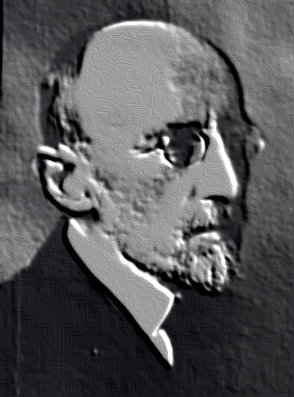

Asher Ginsberg, who became known via his pen name of Ahad Ha-am, was one of the most influential people in this important time.

Ahad Ha-am was born in Skvira, a small town near Kiev in the Ukraine in 1856. He received the traditional Jewish education from the age of three. He excelled in his talmudic studies and became familiar with the various Jewish philosophic rabbinical texts.

He was a strong willed boy who had a tremendous amount of intellectual curiosity. At the age of eight he taught himself to read Russian. By twelve, he began reading the forbidden "haskala" (Jewish Enlightenment) literature. Although he became a "free-thinker" he continued his talmudic education.

He was a fastidious, morally upright person with a strong sense of human dignity. He disliked corruption and vulgarity. He was quiet, reserved and shy and felt that only work was worth doing. He enjoyed deep conversations with friends which gave him his relaxation. Although he distanced himself from his religion, yet he maintained the Jewish dietary laws, said Kaddish when it was necessary, had a reverence for the Jewish tradition.

Although he lived among the Yiddish writers and was fluent in Yiddish, he maintained a contempt for Yiddish. Ahad Ha-am wrote only in Hebrew, and because of his respect for the tradition coupled with his solid knowledge of the Talmud and biblical sources, his writings were enriched and inseparable from Jewish values.

He married a simple and poor Jewish girl who bore him three children. Although she stood by his side through out his life, he always felt a spiritual lonliness. When one of his daughters married a Russian gentile, Ahad Ha-am refused to speak with her for many years, so strongly did he feel his Jewishness, yet he was unable to transfer it to his daughter.

At first Ahad Ha-am wanted to study the works of the "haskala" but he was disappointed in the "maskilim". The maskilim were the authors and thinkers of the haskala movement. With his disappointment in the maskilim, Ahad Ha-am went to study the various secular subjects taught in the universities. He mastered many languages.

In Odessa, he became acquainted with the Hovevei Zion movement. He joined the central committee and became embroiled in many arguments over the method of settling Eretz Israel.

At that time the Hovevei Zion movement recruited candidates to go to Israel. They provided money and support for those who went there to settle. Unfortunately, many were disillusioned in what awaited them in Israel. It was Ahad Ha-am who proposed a rigorous training program in Europe to give the agricultural skills to those who desired to emigrate along with philosophy to carry them through the difficult period of re-adjustment.

It was at that time that he published his first important article, Lo Zeh ha-Derich, (This is not the Way) which advocated dedicated and trained settlement. This controversial essay written under the pseudonym Ahad Ha-am (meaning "One of the People") propelled him into fame as an intelligent thinker and convincing writer.

He continued to write and was adopted as the spiritual leader of the "B'nei Moshe" movement. This movement lasted for about eight years, and his writings were their direct inspiration.

In 1891, Ahad Ha-am visited Eretz Israel and summed up his impressions in Emet me Eretz Yisrael, (Truth from the Land of Israel). He was strongly critical of the economic, social, and spiritual aspects of the Jewish Settlements. He visited a second time in 1893 and published similar criticisms. He planned at this time an educational encyclopedia on Jews and Judaism (Otzar ha-Yahadut) which he hoped would encourage Jewish studies and revitalize Jewish thought. The massive work was never completed, but he became the manager of an influential Jewish publishing house, and the editor of their monthly magazine, Ha-Shilo'ah.

He advocated a continuity between tradition and the emergence of the new Israeli culture. He felt that with out the traditional Jewish values, the Zionist dream would turn into a secular state devoid of inherent Jewish values.

Ahad Ha-am clashed with the other leaders of Zionism, notably Herzl and Nordau. He had no faith in the dream of Herzl to set up a Jewish state anywhere, devoid of Jewish values. Herzl and Nordau's estrangement from Jewish values and culture troubled him. He accused them of neglecting the cultural tradition which he felt were the pulse and soul of the emerging Jewish nation.

When Herzl published his book, "The Jewish State" in 1896, Ahad Ha-am wrote a scathing review of it asking what was Jewish about this proposed state and pointed out the absurdities in it. During the Sixth Zionist Congress, in 1903, Ahad Ha-am expressed his opposition to Herzl's consideration for the British proposal for an autonomous Jewish entity in Uganda.

It was the East European Zionists who insisted on Palestine and caused the rejection of the famous "Uganda Plan". It was due to this defeat that Herzl suffered his heart attack which eventually took his life. After Herzl's demise, Chaim Weizmann and others, together with Ahad Ha-am took over the World Zionist Organization.

Ahad Ha-am was considered an important contributor to the Jewish character of the modern Jewish state. He basically used his excellent mind and writing skills to outline the need for a Jewish character for the new Jewish state.

He settled in Israel in 1922 where he remained until his death in 1927. His essays were not confined to Zionism, but were philosophical analysis of ideas and concepts that affected the life of all men. A man of tremendous stature and influence in his life time, today his works are perhaps too philosophical for a generation of enjoyment seekers.

He explored the desire to live individually, and as a nation. He touched on the attributes of divine mercy and G-d's attributes. He tried to define the essence of a Jew and of the Jewish nation. He explored the consant sub-conscious of the Jew and of the Jewish nation. After the rise of the Jewish State, his ideas reached their fruition as embodied in the Jewish spirit of the Jewish State.

~~~~~~~

from the February 2004 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|