Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

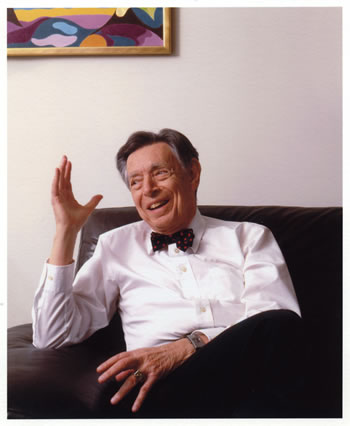

Robert O. Fisch, M.D.

By Phil Bolsta

Fisch, a retired University of Minnesota professor of pediatrics and an international expert on the metabolic disease PKU (phenylketonuria), survived the two most oppressive totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century. A Holocaust survivor, he has been knighted in Hungary for his role in the 1956 revolution against communism. Fisch is also an accomplished artist. Each segment of his first book, "Light from the Yellow Star: A Lesson of Love from the Holocaust," is illustrated with one of his paintings and introduced by one of the biblical quotes carved on the walls of the Jewish Memorial Cemetery for the Martyrs in Budapest, Hungary. The book is distributed at no cost to interested schools through the Yellow Star Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping

educate

young people about the Holocaust. Fisch's subsequent books include, "The Metamorphosis to Freedom," and "Dear Dr. Fisch: Children's Letters to a Holocaust Survivor." For more information, visit www.yellowstarfoundation.org.

My childhood in Budapest was very happy. My

parents

worked very hard. I had nice clothes, good food, many friends, and much love. A devout Catholic nurse with a

nursing degree

named Anna Tatrai lived with us and helped raise me. I was taught to respect others' beliefs and ways of life. I attended Friday service in the synagogue and also Sunday Mass. Just as bridges over the Danube River connect the two parts of my city, Buda and Pest, so it was in my home. Different religions were linked by love and understanding.

On March 19, 1944, nine months after I graduated

high school,

the Nazis invaded and occupied Hungary because the Hungarian government, which was on the side of Germany, tried to make a separate peace. From that point on, every Hungarian Jew had to wear a four-inch yellow Star of David on their clothing.

I volunteered at the Jewish Counsel, an organization that served as a liaison between the Jews and the German commandant. One day, a very excited man came in and asked to speak to whoever was in charge of the Country Division, where I was working. I brought him to the head of the division's office, but instead of leaving I stayed inside the door to listen to what he had to say.

The man described how, in the countryside, all the Jews had been taken to a ghetto. And that one day, unexpectedly, everybody from infants to pregnant women to dying cancer patients were taken to the railroad station, crammed into a cattle car without food and water, and sent off to an unknown destination. When I heard this I realized that it was not just a matter of the Nazis not liking us, it was a matter of they were going to kill us.

Until then, I had been very much afraid of the air raids that were going on. But now I recognized there were only two possibilities — the Germans would either lose the war first, or they would kill me first. From then on, I was happy whenever a bomb fell on the city, because I would rather see the Germans' destruction than my own.

On June 3, 1944, I was sent to a work camp with 280 men from 18 to 48 years old. They fed us well, but were very cruel. When we first arrived, the guards confiscated all our possessions and ripped up our photographs of loved ones. We were told, "You don't need these pictures anymore because you will never see your family again." During air raids, we had to stay next to the stored explosives because they said if we were hit, at least the ammunition would not be wasted.

On January 17, 1945, in the dead of winter, thousands of us started to walk on a death march. In one village on the Hungarian border, we were forced to stay for two nights in an oval brick burner building. It was basically a large furnace room where other Jews were also being held. Many of the prisoners were so weak that the room was filled with "crawling skeletons." The smell of decomposing bodies and human excrement was overpowering. Millions of lice crawled all over us in the dark, and our fingers were soon exhausted from endless scratching.

Two weeks later, an epidemic of typhoid fever, a disease transmitted by lice, broke out. We were in a German village, digging ditches to guard against approaching Russian tanks. I was the first to have a high fever. One by one, prisoners started collapsing around me. At first, the guards started to kick the sick people because they thought we were just pretending to be sick. But it quickly became obvious that it was an epidemic, so they put the sick people in a room in a nearby school building. They provided them with everything possible — medication, good food, and even chocolate, an unheard-of luxury.

Soon, two trucks came to pick up the sick prisoners. The doctor told me that thirty people could go in the truck to the hospital and there were only twenty-nine people in the sick room. He asked if I wanted to go because I was the sickest of everyone. I said, "No, I would rather work, even with the fever." I did not trust them. It was obvious to me that the Germans didn't want to cure us in a hospital. That was baloney. They wanted to kill us. The doctor told me I was crazy not to go and that he never wanted to hear me complaining again. Many prisoners who were well volunteered to go in my place but only one "lucky" one was chosen to be number thirty. All were shot at the edge of the village.

The Nazis were very brutal, but sometimes some of the SS soldiers, even the worst ones, showed us compassion when they were apart from their comrades. I was assigned one day to go to work with the cruelest SS soldier. As soon as we got away from the others and nobody saw him, he told us not to do any work. He even gave us the food he had with him. But as soon as we got back, he started to beat us again.

There were other examples. Once during the march, a guard secretly handed out sandwiches. Another time, solders "mistakenly" gave us more food than the ration permitted. It was a rare glimpse of humanity. It was as if vegetation had miraculously appeared on a rock.

We walked from dawn to sunset every day, often without any food or water for days at a time. Anyone who couldn't walk, who had to sit down, was shot in the head. As we walked through villages, some people gave us food and water, even though it was dangerous for them. One day, in a small village, an Austrian peasant brought a bag of apples to the edge of a fence and started to throw them to us. The reaction of the prisoners was wild. The peasant was immediately shot and killed.

* * * * *

For continuation, go to Page Two

* * * * *

For more articles on the Holocaust, see our Holocaust Archives

~~~~~~~

from the February 2008 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|