Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

European Discovery of Egypt

By Jay Levinson

Note: All photos Courtesy of Bible Lands Museum Jerusalem

While Egypt was a pivotal hub of the Moslem Middle Ages, the Christian world focused its efforts on conquest of the Holy Land. Egypt was relegated to a country in enemy territory, well-known by name from Biblical verses, but seldom visited. As the military politics of the Middle East changed, the attitude toward Egypt was slow to be revised. An exhibit, put together by Dan Kyram at the Bible Lands Museum in Jerusalem, documents what could well be called the European Discovery of Egypt.

Until the fifteenth century invention of moveable type, book-based knowledge was based on books produced by hand, essentially in single copy. Concurrent with the advent of printing was a reawakening to the world at large, which propelled what we have come to know as the Age of Discovery. Together, these two phenomena led to the drawing and distribution of maps, crude in modern terms but a cornerstone of future trade and travel. On display at the exhibit are early maps of Egypt, not at all sophisticated in terms of today's standards.

Slowly, a selected few travelers reached Egyptian (and Holy Land) shores. Not only did they not meet the 21st century stereotype of guidebook in hand and camera dangling around the next. There were no guidebooks, so personal travelogues began to emerge. Even hand-drawings of sites were forbidden, so sketches could be made only from memory, usually long after visitors departed from Egypt or based upon descriptions provided by others. A major influence was Sebastian Münster (1488-1552), a Germanic cartographer and Hebrew scholar who drew the pyramids much too square and totally out of proportion in their dimensions. But, knowledge was spreading, albeit slowly.

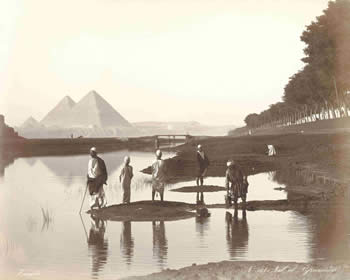

The road to the Pyramids, 1880's, Jean Pascal Sebah

A key date in the European Discovery of Egypt was the defeat and retreat of Napoleon in 1801 after his invasion of the country three years earlier. His soldiers were routed, but his withdrawal from the country was somewhat unusual. Usually a departing army leaves with all of its citizens, but not in this case. The Mamluk régime in Egypt rejected the French occupying force, but it did not turn its wrath upon all Frenchmen. Napoleon left behind some two hundred French scientists, artisans, and scholars. They soon became a link between the Middle East and Europe, and bringing knowledge of the ancient country to the modern world.

An Arab coffee shop in Cairo 1870's, Felix Bonfis

Times were changing. Ottoman rule was being weakened. Mehmet Ali (1769-1849) became the Wali of Egypt in 1805 and soon ruled the entire area, nominally under direction from Constantinople. In good part due to the short Napoleonic rule, sketching of Egyptian sites was no longer forbidden. Images of Egypt made their way back to Europe. Curiosity first centered upon known places, then later on daily life. Egypt had been discovered! An important figure was Daniel Roberts (1776-1864), whose drawings were reproduced by lithography. His mid-19th century drawings are classic, both in Egyptology and the study of Eretz Yisroel, where hee is responsible for one of the early drawings of the Western Wall.

Technology was also moving forward. 1839 marked the invention of photography, although the invention of film was to come only in 1888. It was no longer necessary to draw all sites. Use of the new process spread rapidly, and in the same year Daguerreotype process pictures began to appear. Francis Frith (1822-1898), and Englishman, became the first professional photographer to work in Egypt, and he quickly set about documenting the country's ancient sites. By the 1860s Thomas Cooke was bringing the first organized tours to Egypt.

Another step forward in technology that made photographic prints more common was he albumen silver print process, invented in 1850 by Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard. It allowed photographs to be printed on paper negative. Albumen was used to bind photographic chemicals to paper. This was the primary form of photographic positives from 1860 until 1890.

A bridal coach, 1880's, Unidentified Photographer

The 130 photographs and prints taken chosen from Kyram's collection of over 10,000 items show Egypt literally as it was being discovered --- one picture with only one of the Sphinx two feet uncovered from the sands. Extensive treatment is given to the monuments of Luxor (Thebes in former times and thought to be a primary Biblical era city). A curious "picture" is the 1890 engraving done by Jean Léon Géröme that shows Napoleon juxtaposed aside the Sphinx (69 years after he died).

Not all of the photographs in the collection are of places. After the sites of Egypt were discovered and documented, pictures of daily life in the country provide sociological insight. There are prints of a barber, a grocer, street coffee shops, and forgotten enterprises such as a harness store. In the era before motor vehicles there is even a "Bridal Carriage" mounted upon an animal. Oddly enough, an anonymous 1895 picture of a Large Tourist Group at the Great Pyramid marks the end of the era of discovery. The first Kodak film camera had been invented. Travel was easier, and groups were more common in Egypt. The country was finally open to Europe. It would only be in the early 20th century, however, that pictures of Egypt's Jewish community would become available.

This exhibit is certainly recommended. The pictures of many Biblical era Egyptian sites, before they were besieged by traffic, tourists, and litter, give better understanding to a culture so dominant in the Tanach.

The museum is open Sunday, Monday, Tuesday and Thursday 0930-1730; Wednesday 0930-2130; and Friday 0930-1400. Closed Shabbat.

~~~~~~~

from the June 2009 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|