Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

Songs from Sinai

Jonathan L. Friedmann

Listen to L'shanah Tova mp3

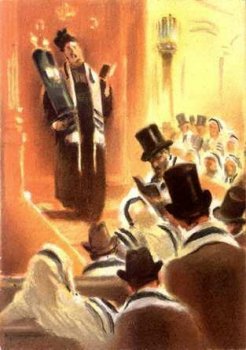

Time-honored music of the synagogue serves as a powerful reminder of the Jews' shared history and common heritage. In Ashkenazi tradition, this is perhaps best demonstrated by the widespread use of Mi-Sinai tunes: melody-types traditionally believed to have been transmitted to Moses on Sinai. In actuality, we have no definitive record of music from the days of Moses; but Mi-Sinai melodies do have a long history, developing in southern Germany and eastern France between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries C.E. These quintessential themes have come to dominate the music of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, and virtually all Ashkenazi Jews throughout the world hear these melodies during the High Holy Days. These ubiquitous sounds unite Jews who might otherwise be religiously or geographically dispersed. They are an audible ritual expression of a collective past.

Among the Mi-Sinai tunes are the High Holy Day settings of Barkhu, Ha-Melech, Avot, Aleinu, and Kol Nidre. Each of these pieces is a seamless mixture of traditional synagogue material and modified fragments of French and German folk and secular songs. Like biblical cantillation, Mi-Sinai tunes are colored by melismas—melodic passages with several notes on one vowel. And in some of these tunes can be traced a number of separate Mi-Sinai motifs. Kol Nidre, for example, is not technically a single melody, but rather an amalgam of seven or eight distinct themes.

The fixing of these songs was spurred on by the spiritual decline of European Jewish life in the fourteenth century, a period of Crusades, the Black Death, and other devastations. Rabbi Joseph Molin (the Maharil), a renowned rabbinic authority of the time, saw the unification of synagogue song as a way to preserve Jewish heritage and devotion. He traveled extensively, serving as hazzan in various locales, and, together with his disciples, established these melodies as traditional ritual. He ruled that Mi-Sinai tunes be given the same authority as if they were handed down to Moses on Sinai—that is, they should never be changed (Orah Hayyim, 619).

Without doubt, the great effort to preserve these melodies reflects the importance placed on historical continuity and group solidarity within Judaism. Eastern European Jews, for instance, gave these tunes the elevated status of skarbova, meaning "antique" or "old." More specifically, the term refers the songs' "official" status, indicating that, from the time of their genesis to the present, they are considered obligatory in the High Holy Day services; no other melodies may be substituted for them. Musicologist Macy Nulman described the lasting effect of codifying this music: "To this day, these melodies that stir the heart and infuse awe and devotion in one's prayer, are essential elements of the synagogue service and remain a unifying force in Jewish life." In a very real sense, then, Mi-Sinai tunes provide Jews a link to a shared sacred past, announcing to the community that "What we do has a history; we ourselves have a history."

Listen to L'shanah Tova mp3

Jonathan L. Friedmann is Cantor of Bet Knesset Bamidbar in Las Vegas, Nevada, and the editor of four books: Jewish Sacred Music and Jewish Identity (Paragon House, 2008); The Value of Sacred Music (McFarland, 2009); Music in Jewish Thought (McFarland, 2009); and Perspectives on Jewish Music (Lexington, 2009).

~~~~~~~

from the September 2009 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|