Their words still give me cause to pause and sigh. They reawaken in me knowledge of the harsh realities of past suffering and violence borne out of indifference and hatred.

As I translated each of this cemetery's inscriptions, I read of the character and qualities of the Bialystoker Jews, of "perfect and upright men" and "modest and God-fearing women". On their tombstones are also words of praise for great rabbis, scholars, and charitable women. Old age is recorded as a triumph, especially in the case of an Abraham son of Israel who lived to be 102 years old. What history Abraham must have seen and experienced from 1830 to 1932, the century and more of his life! (Image 2) Occasionally, the lesser qualities of the deceased are remembered, as one father wrote of his daughter: "Her mouth ceased from (its) evil tongue" – she gossiped! (Image 3)

(Image 2 Abraham "a son of 102 years")

(Image 3 Fragment of the tombstone of a daughter of R. Israel "whose mouth ceased from (its) evil tongue"

These inscriptions also hold details that were sadly normal to life in a world a century ago in Bialystok, Poland. Inscriptions remember women who died in childbirth, especially in the cold winter months, women who died before they could marry, and a man who barely experienced the joy of fatherhood before his untimely death. And then there are the tombstones of children. Perhaps the most heart wrenching inscription is that of three sons – Chaim Lejb, Shalom Shechna and Israel Abraham, aged eight, six and four, who died in a fire in March of 1908! How did their father, Asher, and their mother endure this loss? Such deaths, though sad, are not unique to Bialystok; they were part of life without the comforts of the contemporary world. (Images 4, 5)

image 4

image 5

(Images 4,5. Left: "Here lie children burnt by fire. They are indeed Chaim Lejb, 8 years old, Shalom Shechna, 6 years old, and Israel Abraham, 4 years old, sons of R. Asher Topolski." Right: "They were burnt on Wednesday 15 Adar II year 5668 [18 March 1908]. May their souls be bound in the bond of everlasting life.")

Yet in 27 of the 100 sections of this cemetery, from sections near its entrance to those distant sections adjacent to the nearby Catholic cemetery, I also encountered the inscriptions of Jews who died not from natural causes or death due to the harshness of life in the early 20th century, but from death brought on by "the bloodshed of his or her days". These inscriptions evoke remembrance of the violence of anti-Semitic acts or pogroms that assailed the Jewish community in Bialystok in July 1905, October 1905, June 1906, April 1907, May 1908, March and July of 1911, and in nearly every year from 1918 through 1936, with one inscription recalling such bloodshed in June 1943. The persecutors were the Tsarist Russians, the Poles, the Nazis and the Soviet Russians.

Each time I encountered such an inscription, I would be reminded of this harsh time for the Jewish community; however, on four particular occasions I encountered inscriptions that would forever be etched in my mind and engraved on my heart. One such inscription in Section 76 told of the violent death of Dabe, the nine year old daughter of Reb Chaim Kaplaski. Dabe was killed on 19 August 1920 in Bialystok, amidst the violence that assailed the Jewish community as the Red Army entered Bialystok in late July, just three days before the Polish army recaptured the city.3 Her inscription begins with a poem: "A blossom is fresh, a flower is tender. Before it fully ripened, it was plucked, it was killed." This beautiful first stanza, likening this precious daughter to a fresh blossom and a tender flower, is ever so quickly shattered by the imagery which follows. This little girl, Dabe, had not yet 'ripened'. She had barely experienced a decade of life before she was killed. Dabe was denied life. Not only the stark imagery of this poetry stays vividly with me but also a coincidence – if there is such a thing as coincidence! The day that the image of Dabe's tombstone was captured, a red (artificial) blossom fully in bloom lay beside it. I do not know how many people come to visit Dabe's grave or if they even know Hebrew to recognize how beautifully eerie it was to find a red blossom beside these words that remember a young girl, not yet a blossom, killed in the violence of August 1920. (Images 6, 7)

image 6

image 7

(Images 6,7 Red blossom beside the base of "the girl Dabe daughter of Chaim Hacohen Kaplaski")

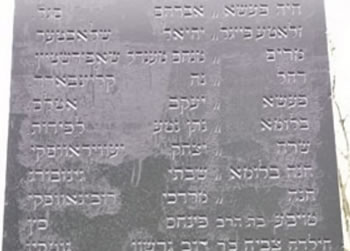

I thought that the feelings I had experienced after reading Dabe's inscription (and seeing the red blossom) would not be matched until I came to the inscriptions in Section 26, the last inscriptions to be translated in this entire cemetery. I had already encountered 35 inscriptions with phrases bespeaking violence in 26 other sections in this cemetery. But as I translated the last inscriptions from Section 26, I encountered 13 such inscriptions, one after another. Eleven remembered victims of the June 1906 Pogrom, one a woman victim of the July 1905 slaying, and the last, another woman killed in April 1907. Why were so many inscriptions placed in this section? Quite simply, because beside this section is the black pillar that remembers the Pogrom of 1906 (Image 8). The inscription at the top of the pillar's first façade reads:

A Memorial of sorrow for us, inhabitants of Bialystok and for all the house of Israel, this pillar is a witness for us and for our sons that on the 21st, 22nd, 23rd, 24th, 25th to the month of Sivan year 5666 (1-5 June, 1906 [OC])4 the inhabitants of this city fell upon our brothers, the sons of Israel, plundering at noontime and plundering houses and possessions and they murdered about 80 men and women and children. (Image 9)

(Image 8 Memorial Pillar to Pogrom of 1906)

(Image 9 Opening Words on Memorial Pillar)

Until I translated these 13 inscriptions, I thought that this pillar was the only memorial to the victims of the 1906 Pogrom, yet now I realize that Section 26 also serves this purpose. Most of the names on the tombstones are also found on this black pillar. Yet this black pillar – just like this cemetery – does not only remember the Pogrom of 1906, it also remembers those who died in the months preceding this pogrom, as anti-Tsarist forces within Bialystok struggled with the Polish and Russian armies.5 Thus, on the pillar are also the names of the 42 Jews slain on 30 July 1905, and the five Jews slain on 31 October 1905. For each of these attacks, men are listed first, followed by boys, then women and finally, girls.

As I compared the names on the tombstones with those on the pillar once again I was reminded that these are not only names I seek and words I translate. These names also belong to people who once walked the streets of Bialystok, of young people with dreams for the future, of parents with love and hopes for their children, and children for whom this should have simply been a time to play.

I matched the names on the tombstones with those on the black pillar. The ages of those murdered, however, are not engraved on either tombstone or pillar; they are recorded in the Bialystoker Memorial Book.6 On one tombstone I read the lament for the bride-groom Awrom Izchok, 18 years old. (Image 10) On the pillar, however, just the name Awrom Izchok son of Jonah Hacohen Lewartowski appears. The Memorial Pillar does not tell us Awrom was never allowed to marry. His inscription offers this detail, compelling us to ask: What must Awrom's future bride have felt at the loss of the man who would be her spouse, the man who would become the father of her children?

(Image 10 "the martyr, a God-fearing bride-groom, the honorable teacher Awrom Izchok son of our teacher the Rabbi Jonah Hacohen Lewartowski. He was killed by the hand of murderers on Friday the eve of the Holy Sabbath 22nd Sivan 5666 [15 June 1906] as the abbreviated era. May his soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life."

On another tombstone, "the praiseworthy, Ms. Blume daughter of Nathan Nata Lapidus" was remembered as having been killed on 14 June 1906. She was 20 years old. (Image 11) On the black pillar her name appeared after men and boys killed in the 1906 Pogrom. (Image 12) On another broken tombstone were the words: "the important young man Aron Mojsze son of our teacher Nathan Nata Lapidus".7 Aron Mojsze was also slain on 14 June 1906. (Images 13,14) No doubt Aron was the brother of Blume. He was 19 years old. As I searched for Aron's name upon the black pillar, I found it in the men's list. Just above his name was that of another son of Nathan Nata Lapidus! His name was Mordechaj; he was 21 years old. (Image 15) On which day in June was Mordechaj slain? No tombstone remains to provide this detail. To read these three names upon their tombstones (when extant) and the Memorial Pillar evoked the powerfully personal nature of these words. Blume and Aron Mojsze Lapidus, daughter and son of Nathan Nata Lapidus, and also Mordechaj Lapidus, another son, died in the Pogrom of June 1906. Three children killed perhaps on the same day – what must their father Nathan Nata have endured? What of the anguish of their mother who carried, bore and nurtured these children now young adults? This pogrom devastated the entire Lapidus family. Those slain are no more, but a new suffering no doubt emerged at that time for those who did survive, for fathers like Nathan Nata, for wives and mothers, and for their community.

(Image 11 Fragment of tombstone of Blume Lapidus: "the praiseworthy, Ms. Bluma daughter of Nathan Nata Lapidot. She was born 17 Tamuz 5644 [10 July 1884]; She was killed by the hand of murderers Thursday 21 Sivan 5666 [14 June 1906] as the abbreviated era. May her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life.")

(Image 12 Blume's name on Memorial Pillar, sixth name from top)

(Images 13, 14 The only two extant fragments of the tombstone of Aron Mojsze Lapidus. At left: "the important young [man Aro]n Mojsze son of our teacher [Nathan Nata] Lapidus." At right, "[He was born] Adar 5646 [February 1886]. [He was killed by] the hand of murders. [2]1st Sivan year [5666] [= 14 June 1906]. May his soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life.")

(Image 15 The names of the two brothers Aron Mojsze and Mordechaj, sons of Nathan Nata Lapidus,

on the Memorial Pillar, second and third entries from bottom)

Two other tombstones, remembering those slain in the violence preceding the June 1906 Pogrom, also reveal the traumatic yet personal side of this devastation. In Section 16, an Esther is remembered as a victim of the slaying in late June of 1905, ironically on the day called the Sabbath Nahamu "the Sabbath of Consolation".8