Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

KRAKOW GHETTO1

By Rita B. Ross

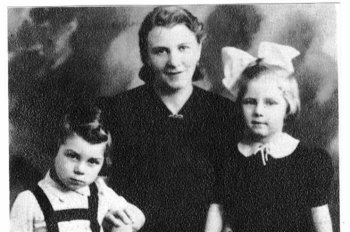

"In the winter of 1942, my mother, brother and I took refuge in the Krakow Ghetto after spending 6 months, running, hiding and posing as Polish Catholics. The following are my lasting memories of the Ghetto.''

Yisgadal ve-yiskadish sh'mei raba," An old man is running back and forth on the streets wailing the mourner's prayer, the Kaddish. His palms are open toward the heavens; his eyes are closed even though he's running. He is wearing a torn black coat and his dirty ritual fringes are slapping the backs of his legs. We have passed the Ghetto many times while we walked the freezing streets of Krakow. And now that we are inside my mother shields our eyes when we walk by. "Shhh, don't look," she says to us, afraid that we may retain some of the ghastly images. She makes us keep our eyes on the ground. No wonder. It is a glimpse into a nightmare.

The Ghetto is filled with noise and the smell of garbage and decay. We see another old man in rags as we walk along the sidewalk. He looks dazed and approaches us, grabbing my mother by her lapels, and pulling her close to him. "Have you seen my sister Chanya?" he asks in a raspy voice. "No, I haven't," she answers him patiently. He takes hold of her hands, pulls them towards his mouth and starts to kiss them. "You look just like Chanya. Didn't you see her?" My mother is gentle with him. "I'm so sorry," she tells him, pulling her hands slowly away from his grasp. "When did you last see her?" she asks. He shrugs his shoulders. He doesn't remember. He starts to cry, "Everybody is gone. Everyone in my family is gone. Only Chanya is still alive. Have you seen her?" he asks for a second time. He sinks to the sidewalk, buries his head in his knees, and weeps.

All around me people are weeping, begging for food, scratching the red sores on their infested bodies, staring vacantly into space. She stops a young man in a black jacket that appears to be some kind of uniform, but his trousers are ripped, his shoes are scuffed, and he wears no socks. He bears no resemblance to the well dressed officers I am used to seeing. "Prosze bartzo, (Please, excuse me)," she says to the young man. "Can you tell me where I can find a room?" He looks at her and laughs sarcastically. His pale face is thin, and has the unhealthy pallor of someone who hardly ever goes outdoors.

"Pani zartuye, (The lady must be joking)," he answers. "This place is so full you can't get an empty paper bag into this space. Anyway, it isn't up to me. Go knock on doors. Maybe someone died and there is room in one of the flats." My mother nods, "rozumye, (I understand)."

The Gestapo has rounded up the few able bodied Jewish young men and assigned them the job of policing their fellow inmates. It is their duty to enforce the rules imposed on their fellow Jews, to report any infractions, and to act as agents for the Gestapo. For this service, they are rewarded with a black uniform jacket and the illusion of power and control. While many of them are protective of the Ghetto dwellers, others become zealous enforcers of the rules, eager to catch the Jews transgressing: hoping to score points with the Gestapo. Life in the Ghetto is filled with suspicions and humiliation.

A cocky teen-ager, swaggering in his new uniform stops an old man and makes him empty his pockets. He squares his shoulders insolently, hikes up his pants, and speaks in Yiddish, "Just because you are old, doesn't mean you can't smuggle." The old man shakes his head in disbelief, "Such behavior from a Yiddishe bocher, (a Jewish boy). That I had to live to experience such rudeness, such chutzpah!" He shakes his head in disbelief.

We continue walking and looking around before approaching one of the buildings. My mother knocks on the door and a woman peers out cautiously. Her head is tightly swathed in a kerchief, she is gaunt, like a pencil and her threadbare housedress hangs on her like a shroud, but her eyes are on fire, and she recognizes my mother. "Freda," she exclaims, "why are you here?" She embraces my mother. It turns out that she is from Wieliczka, the rabbi's wife. "We thought you were on your way to America by now."

My mother, although frightened, seems relieved to see a familiar face. She sighs, "It feels so good to be among my own people, to know that there are still some who are alive, if you can call this being alive." She remembers the purpose of her visit and looks around the dark corridor. "Is there any room for us in your flat?"

"What do you mean 'is there any room for us?' You are us. Do you think we can't make room for one of ours? It will be an honor and a privilege to have you in our little room, although, I must warn you, it isn't what you're used to."

"What I'm used to?" my mother asks no one in particular, following her up the fetid stairs, through a narrow hallway littered with garbage and smelling of sewage. "What I'm used to is freezing in the cold with my hungry children."

"This is it," she exclaims, flinging one of the doors open. "It isn't much, but you are so very welcome." It is a tiny dark room, the little bit of light that comes in is filtered through one grimy window. The room is filled with people of all ages; so close together that it is impossible to get from one end of the room to the other without stepping over a sleeping body, or bumping into someone standing and praying. Two men, wearing black hats and tzitzis, (fringed garments), are standing, facing the wall, swaying vigorously to and fro and from side to side, their eyes tightly shut, praying to their unresponsive God. A woman lies on a cot next to the wall, coughing uncontrollably into a blood soaked handkerchief. A teenaged boy leans against a window, his hands covering his eyes, not moving. Everyone is in his own little world.

The rabbi's wife seems to be in charge. "Move over, please, we have new guests," she tells a woman who is lying on the floor, staring at the ceiling. "We have to make room." Everyone stops to look at us.

The room has two cots and several chairs. Each person sleeps for about an hour and then the next one in turn wakes the sleeping one up by gentle nudging or assertive pushing, demanding the space. No one cares that the bedding is never changed, that lice are crawling over the blankets, that the smell of the person who just got up is rank and clinging. All they want is an hour of uninterrupted sleep; an hour to escape.

I look around the squalid little room and shudder. "God, I don't belong here," I say to myself. "I am a Catholic girl, Maria Kowalsczik. I belong in church kneeling in front of the Virgin Mary. Why am I here?" I hate this room with its awful sounds and putrid smells. I hate the dying people, the coughers, the weepers, the oozing sores, and the hopeless visions. I would rather be back on the cold streets or burning up with fever and hallucinating. I want to be anywhere but here. All of us in this room are together because we are Jews. We have nothing in common yet we are all staying here in one room, together. Some have given up hope; they sit and stare into space. Others are waiting to be rescued. They are making plans, trading gloves for socks, belts for purses. The very religious pray for Moshiach, the Messiah, to come. The so-called enlightened ones are waiting for the world to come to its senses and stop these heedless killings. No one's prayers are answered.

The children almost never leave the room .We play indoors, under the table, constructing a make-believe world. My mother, because of her Aryan looks, is pressed into service by the rabbi's wife. She hands her a black wool coat, "don't ask where it comes from," she says, "just take it and wear it. The owner will never use it again." She is sent out to forage for food for the rest of the inhabitants in our little room, a trip she will make many times in the coming weeks. She removes her Star of David armband and is escorted by one of the Jewish guards to the Ghetto gate. He opens the gate for my mother and she trudges alone through the snow covered Krakow streets, bargaining with the shop keepers, for potatoes, half rotten carrots and anything else she can get for the few zlotys she has acquired from her roommates. She wants to pay for the food herself, but the rest won't hear of it. "We still have our dignity," a woman says, pressing two zlotys into her hand. My mother agrees. She may need her money for the future. She tries gathering as much food as she can. She is not particular about quality. We are many, and we are hungry, but we share everything equally.

While my mother is away, Bubbi (my younger brother) and I stay in the room, playing under the table with the other children. In that small space we feel safe and protected until evening comes and then panic assaults my heart. It is dark and she isn't back. I take up my vigil at the dirty window, waiting with her picture tucked up in a corner of the pane. I experience unimaginable terror; she has been caught, she is being tortured, mutilated. In my mind, I see her beaten and bloodied. I am preparing for the worst. Even though I am just not yet six, I have been listening to many adult conversations for a long time and know all about the things that happen to Jews who are found outside the Ghetto. I have already had first hand experience with people I love never being seen again.

It doesn't take much for my active imagination to take root and transport me to the forest of "Hansel and Gretel." My mother is gone. We are alone. What if she never returns?" I will not be able to survive. Bubbi and I are alone with no relatives to turn to. Dangerous forms lurk in every shadow, just as they do in the illustrations of the frightening stories my mother read to us before the horror of our reality set in. Now she is gone and it is difficult for me to separate my harsh world from the fairy tale. No one has the patience to comfort us. Everyone in the Ghetto is hungry and preoccupied. No one thinks about reassuring two small frightened children. I am dreadfully alone, afraid that we will never see her again. It doesn't take much imagination to see us as orphans, alone in the world with no one to take us in, a fate that so many children I know are facing.

Suddenly, she's here. She's safe and beautiful and smelling of snow. She has had an exceptional day outside the Ghetto. She comes in with a loaf of bread, three tiny potatoes, a jar of yogurt and a maggot- infested slab of meat. The kosher people won't eat the meat, but we do. "This is war," my mother tells us, "you eat whatever you can."

As long as my mother is nearby, I feel safe and protected. My mother tries to shelter us from devastating realities that are occurring all around us, but I don't buy into that. She promises that things will get much better when we get to America. "You'll see," she tells us, "we will have so much food that you are going to beg me to stop feeding you. You'll each have a beautiful room to sleep in, many toys, and a closet full of warm clothing."

"Will Papa play ball with me?" Bubbi asks hopefully.

"Everyday," she answers emphatically.

"Will we be able to go to school?" I ask, hopefully.

"Able?" she asks incredulously. "You have to go to school. In America everyone goes to school."

"Can I be Jewish in America?" Bubbi asks anxiously.

"Yes, of course you'll be Jewish. You will always be Jewish. In America, there is no anti-Semitism."

I turn to ice with apprehension. "I don't want to be Jewish. I want be able to go to church. I want to be like everyone else. I've been Jewish longer than I want to be. I want to be a Catholic," I protest. "I hate the Jews. I don't want to be Jewish, not now, not ever." I am in tears. I quickly forget the promises my mother has just made to us about the wonderful life in America. In no time, I am back to reality and the sordid life we are living only because we are Jews.

"Maidi, Maidi," my mother rocks me gently. "When we get to America none of that will be happening. You can be Jewish and live in a beautiful house, with a nice big garden. You papa will buy you anything you want, and you will never have to see people suffering because they are Jewish."

I don't believe her. I resolve that when I am free, I will become a Catholic again. I promise myself that I will never have to suffer like this. But Bubbi buys into her promises. Her stories about my father are so real for Bubbi that he thinks my father is just around the corner. Every time my mother meets a male acquaintance Bubbi tugs at her sleeve, impatiently, "Ask him," he lisps, "ask him. Maybe this is our father."

My mother begins to realize that I am aware of what is going on around me. She knows I no longer believe the stories she tells me to assuage my longings and fears. The conditions in the Ghetto are deteriorating and no amount of magic and make believe can make me deny what I am seeing around me. There is no longer enough food left to share and people are sick, starving and dying all around us. The illness, starvation and hopelessness of the Ghetto are taking a toll on the living. Those who don't starve or succumb to illness vanish. The dead lie in the streets and no one is strong enough to pick them up and bury them.

All this I see with my own eyes open wide. My mother, who likes to attribute all the unpleasant things I hear and see to my imagination has stopped trying to cheer me up. She has had enough. One night, she collapses on the cot. She covers her face with her hands and sobs quietly. The coughing woman has not awakened. She hasn't coughed or moved since early morning, and I can tell that something is terribly wrong. The rabbi's wife, though weak and starving herself, takes over. "Her body can't stay in the room with us. We have to have it removed. Let me see what we can do." Three of the Jewish guards come into our room. They are going to fetch the committee that prepares bodies for burial. I am not going to watch. I hide under the table and wait for them to take the coughing woman away. I don't ask where they are taking her. I'm afraid I might find out the truth and that it may be more frightening than not knowing.

Later on that very night, my mother quietly packs our few possessions, takes us with her and leaves the Ghetto with the men who are taking away the body of the coughing woman.

* * * * *

Rita Ross was born in Vienna, two years before the annexation of Austria, just as Hitler's troops stormed the country. She spent the war years hiding her Jewish identity and came to America in 1945.

Running from Home, Hamilton Books, can be ordered directly from www.ritabross.com.

1

Selections from Chapter 15 of Running from Home, A Memoir by Rita B. Ross, Hamilton Books. See website www.ritabross.com.

~~~~~~~

from the January 2010 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|