Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

Esther of Bialystok

By Heidi M. Szpek, Ph.D.

She was important, upright, modest, and extraordinary in the performance of good deeds. She was kindhearted, pleasant, precious,

and God-fearing. She was a girl, a young woman, not yet a mother, a mother, and an elderly woman. She was a martyr, a Rabbi's wife,

the descendant of a prominent rabbinic lineage, the crown of her children's head, and an Eshet Hayil – a "woman of valor". Such

are the virtues and character of not one Esther but of the 38 women named Esther as remembered in the extant Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian

and Polish inscriptions on the Jewish tombstones in the Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery in Bialystok, Poland.1 Of the over 2000 extant inscriptions, nearly half remember women (including

girls). Among these women, the name Esther is rivaled only by that of Chayya and Sarah. Each time I translate the inscription of an

Esther I contemplate whether Bialystok's Esthers emulate their namesake, the biblical Esther, or the rich legends of Esther preserved

in rabbinic literature.2

Many of the virtues accorded Bialystok's Esthers are shared with the Sarahs, Hannahs, Rachels, Rebekahs, Leahs, Feigas, indeed

with all the women who once walked the cobblestone streets of Bialystok's marketplace (Image 1). These virtues, as we will see,

offer us a window into the character and role of Jewish women in the late 19th to early 20th century in

Bialystok, Poland, where women were especially extolled as wives and mothers. Thus, the death of a daughter still a child was

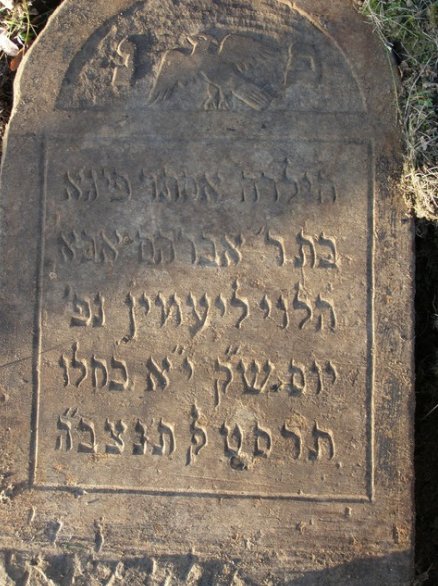

grieved not only as tragic, but also because of her unrealized potential. Such was the sad fate of the 'yaldah' young girl,

Esther Feiga, who died on the Holy Sabbath 11th Kislev 5669 [5 December 1908], never having the opportunity to light the Sabbath

candles.3

Image 2 Inscription of the girl, Esther Feiga

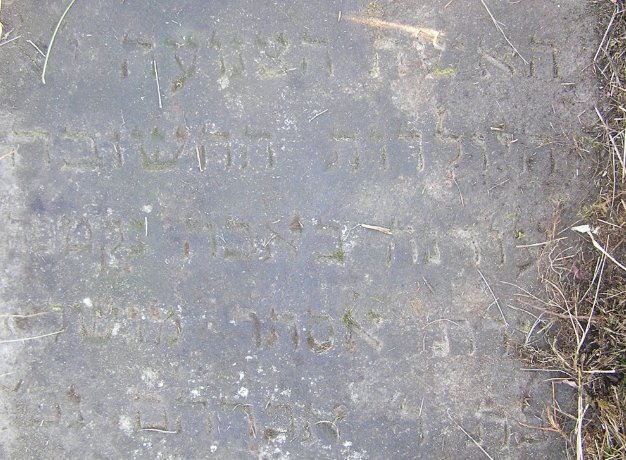

The inscription of another Esther, the daughter of R. Chaim, who passed away before marriage, mourns the loss of this unmarried

(literally "virgin) young woman (Image 3). This Esther is one of 34 young women whose life was abruptly 'broken' as depicted by the

broken tree upon many of their tombstones (Image 4). Childbearing, especially in the cold winter months, took its toll on Esther

Moszka who died in childbirth in the harsh winter of 1896 (Image 5), one of eight women remembered as losing their life in the

bringing forth of new life in the years 1896 to 1910. As for Esther Feiga, a daughter, a wife and a mother, her inscription remembers

the centrality of motherhood to the household and the grief of her untimely passing: "Our eyes shed tears because our mother was

taken from us, the crown of our head, the important and modest woman, the married Esther Feiga daughter of R. Shabbatai Hacohen

Kaplan" (Image 6). Such tragedies were sadly inherent in this time period, giving cause for celebration to women (and men) who

reached old age.4

Image 3 The precious unmarried Esther daughter of R. Chaim

Image 4 Bird atop broken tree of "the precious unmarried Liba"

Image 5 Detail of inscription of "Esther Moszka" who died in childbirth

Image 6 "Our eyes shed tears because our mother

– Esther Feiga – was taken from us"

Yet women's roles were not limited to that of wife and mother. Women were also nurses, social workers, administrators for

Linas Hatzedek, which gave aid to the poor and sick, and for the Bialystok Relief Society. Women were students and

teachers; they served in the administration of the Bialystoker Youth Society, one organized and served as 'mother' of the

Bialystoker Orphans. Women were youth athletes, founders of the Maccabi Sport Club, and actresses in the Habimah

Players. Women were needleworkers at the "Ort" workshops in Bialystok, active Zionists in Poale Zion and embraced the

socialist ideals of the Bundists. They sat on strike committees as early as 1901, and continued to march against unfair labor

practices in the 1930s. Women managed their late husbands' estates, served as leaders in the Bund, even dying in the tragic

Sabbath Nahamu in July 1905 when the Tsarist Army rose up against the protesting Jewish Bundist workers.5 Though a woman's tombstone inscription may offer such 'simple' epithets as

"important" or "modest", a glance through the photographs preserved in the Bialystok Photo Album visually demonstrates that

such seemingly basic terms humbly hold within them the rich legacy of Bialystok's women, including each Esther of Bialystok. Perhaps

in the humbleness of these simple epithets we can glean a resemblance to the Biblical Esther, a woman who humbly accepted the

important role of queen to the Persian King Ahasuerus as a means to eventually save her people.

Extant inscriptions of Bialystok's Esthers do not explicitly link these women to their biblical namesake Esther as compared to

several such inscriptions from the Ukraine, in which verses from the book of Esther are incorporated into an Esther's

inscription.6 However, in three extended epitaphs of an Esther in

Bialystok, two crafted as exquisite acrostic poems, connection of the deceased with the Biblical Esther is subtly suggested. In the

first of these inscriptions Esther daughter of Zwi is remembered by key virtues of modesty, uprightness, generosity, and

kindheartedness. Esther, the daughter of R. Zwi and the wife of Becalel Nowik, died on the eve of the Holy Sabbath 19th Elul 5663

[1903], a moment when traditionally she should have been lighting the Sabbath candles. Esther is then extolled by an acrostic poem

arranged both vertically and horizontally to spell out her name and lineage – Esther daughter of Zwi (Image 7):

Image 7 Esther daughter of Zwi

[E] A compassionate mother you were to your sons;

[S] a treasure to the husband of your youth;

[T] you were always honest;

[R] many righteous deeds [B] in secrecy you performed [T);

[Zwi] the splendor in your paths is a desirable thing.

Just near the gravesite of Esther daughter of Zwi is a tree-shaped monument whose inscription is crafted so as to resemble

a plaque affixed by a rope to a tree (Images 8, 9). On this plaque another Esther is remembered:

Image 8 Esther daughter of R. Aperdik

Image 9 Inscription of Esther daughter of R. Aperdik

"Here lies a proper, God-fearing and upright woman, [in] secrecy she performed her many righteous deeds. Our beloved and

precious mother, Esther daughter of R. Aperdik. She died Tuesday 11th Tishri 5669. May her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting

life. [In Russian] Estera Wolkomirskaya.. She died 24 October 1908."

In these two inscriptions alone – both of Esthers of Bialystok – is the character trait of 'secrecy' in

performing righteous actions recalled, bringing subtle allusion to the biblical Esther whose name means 'one who conceals'7 and whose character was distinguished by her ability to patiently conceal her

identity until the moment was propitious to save her people (Esther 2:10; 7:3).

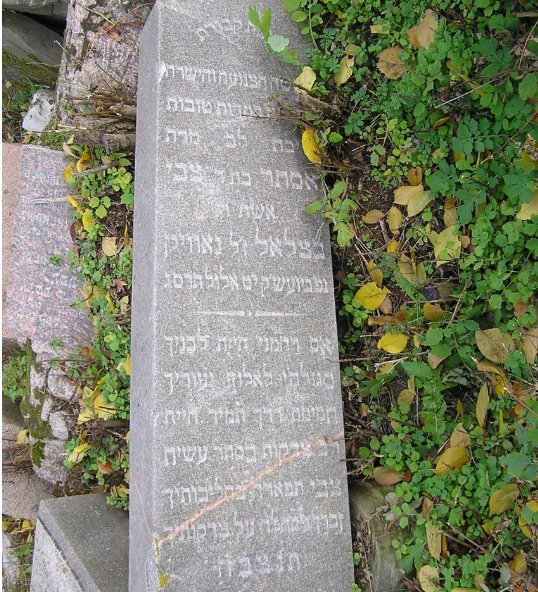

Lastly, in this same section of the Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery one final Esther, Esther Golda, is remembered through a mosaic of

biblical allusions that evoke the character of the biblical Esther (Image 10):

Image 10 Esther Golda

"Here rests the modest, precious woman, a woman of valor, a hospitable woman who educated a Jewish generation and a Jewish

home; all her toil was to teach her sons in accordance with the testimonies of the Torah and Jewish religion; she reaches out her

hands to the poor, the married Esther Golda daughter of R. Jakob Isaiah belonging to the house [family] of Rozenthal. May her soul be

bound in the bond of everlasting life. She died Sunday 19th Cheshvan 5658 [14 November 1897]."

The modest, precious Esther Golda is specifically called an Eshet Hayil, a "woman of valor", whose charitable acts

toward the poor are remembered by a direct quote from Proverb 31:20 "she reaches out her hands to the poor", the biblical proverb

which describes a woman of valor. However, the intervening details of her inscription provide implicit reference to connect Esther

Golda with the Jewish tradition of the biblical Esther. Esther Golda's energies were focused on sustaining Jewish customs for her

immediate time and on transmitting this knowledge to her sons, the next generation, in accordance with the teachings of the Torah and

Jewish religion.8 In this emphasis on preserving the heritage of

Judaism, Esther Golda parallels the desire and efforts of her biblical namesake.

Rabbinic tradition emphasizes that Queen Esther maintained her devotion to Jewish ritual law. Her seven maidens were Jewish, each

with a name bestowed on the maiden to ensure that Esther would be reminded to keep the Sabbath. Esther likewise maintained a

kosher diet, eating only vegetables as had Daniel and his three friends in Nebuchadnezzar's time.9 The biblical tradition records that Esther was a woman of courage, a

beautiful and wise a woman who followed the guidance of her uncle Mordechai, who challenged court etiquette to approach King

Ahasuerus though not summoned, with a strategy that brought about the due punishment of the wicked Haman and the survival of her

people. However, the biblical tradition also emphasizes that Esther approached the king a second time (9:25). This second daring

approach by Esther resulted not only in the punishment of Haman but also in the official recognition of the days of Purim in order to

remember what "they [the Jews] had faced in these days and what had happened" (9:26). Queen Esther gave full written authority that

"these days should be remembered and kept throughout every generation, in every family, province, and city; and these days of Purim

should never fall into disuse among the Jews, nor should the days of commemoration of these days cease among their descendants"

(9:28). In the subtle yet poignant words of Esther Golda's inscription, this Esther of Bialystok is likened to the Biblical Esther

in her similar devotion to maintaining Jewish ritual traditions and in transmitting this heritage to the next generations.

Twentieth Century scholarship questioned whether Jewish epitaphs held words that directly related to the deceased or to Jewish

tradition through the ages.10 As I translate the inscriptions of the

Esthers of Bialystok, in the back of my mind are the words of these 20th century scholars. Yet as I consider the epitaphs

of the Esthers of Bialystok in light of the historical, social and religious milieu of Jewish Bialystok, I beg to differ with past

scholarship. I see the Esthers of Bialystok united with the other Jewish women of Bialystok through the virtues they share, virtues

that are not only representative of late 19th to early-20th century Jewish women, but also part of a continuum

of virtues Jewish women strive to emulate, originating with such foremothers as Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel, Leah … and Esther. And

I see in the subtle yet creative crafting of acrostic poems and a mosaic of biblical language an intentional desire to connect

Bialystok's Esthers with the biblical Esther who sought to preserve Jewish tradition through her silent and subtle acts of

righteousness.

Heidi M. Szpek, Ph.D. is a Professor of Religious Studies and Philosophy at Central Washington University (Ellensburg,

Washington), currently writing a book on the Jewish epitaphs from Bialystok, Poland. Her most recent journal articles on Jewish

epitaphs include: "In the Bloodshed of Their Days" in the Jewish Magazine (January 2010); "Wooden Matzevoth" (with Tomasz Wisniewski)

in The Jewish Magazine (October 2008); "He Walked Upon a Wooden Leg: Epitaphs and Acrostic Poems on Jewish Tombstones" Legacy of the

Holocaust Conference 2007 Conference Proceedings. Jagiellionian University Press. Krakow, Poland (May 24-26, 2007), 2008; "'And in

Their Death They Were Not Separated': Aesthetics of Jewish Tombstones." The International Journal of the Humanities. Vol. 5 (2007):

165-178; and "Oh Earth, Do Not Cover My Blood!": Eastern European Jewish Identity and the Material Culture." The International

Journal of the Humanities. Volume 4.4 (2006): 7-18.

Photographs copyright permission: Tomasz Wisniewski. Special thanks to Sara Mages for her "second set of eyes" in

translating the epigraphs of the final three Esthers.

1

This cemetery, also called Bagnowka Jewish cemetery after the district of Bialystok in which it is located,

was established in c. 1890. It lies adjacent to a Catholic cemetery which in turns rests beside an Orthodox cemetery. Bagnowka

Jewish cemetery once covered nearly 45 acres and was divided into 100 sections, which cradled the remains of nearly 45,000 Jews from

Bialystok and surrounding smaller towns. Today, due to the ravages of Jewish material culture during the Holocaust and further

devastation under Communism, the cemetery has been reduced to about 30 acres. Approximately 2100 matzevoth (tombstones)

remain, in various states of disarray. The tombstones were photographed by Polish historian and journalist Tomasz Wisniewski

beginning in 2006 until just recently and translated by Heidi M. Szpek. Wisniewski's study of this Jewish cemetery in Bialystok

began in the late 1980s, documented in numerous journal and magazine articles, a site survey, a book Jewish Bialystok and

Surroundings in Eastern Poland and an extensive photographic record. Today, all images and translations of Bialystok-Bagnowka

Jewish cemetery can be found at www.bagnowka.com, along with thousands of images and translations

from other Jewish cemeteries, predominately in present day Poland. In addition, www.bagnowka.com

contains thousands of old images, postcards, maps and documents related to the now lost world of Eastern European Jewry, especially

in northeastern Poland.

2

See Bernard Grossfeld, First Targum to Esther. Sepher-Hermon Press, 1983; The Targum Sheni to the

Book of Esther: A Critical Edition Based on Ms. Sassoon 282 with Critical Apparatus. Sepher-Hermon Press, 1994; The Two

Targums of Esther. The Liturgical Press, 1991. (I was fortunate to have studied with and served as a research assistant to this

esteemed Targumic scholar in my college years.) A synthesis of rabbinic literature related to Esther can be found in Louis Ginzberg's

Legends of the Jews. Vol. IV, Vol. VI. Jewish Publication Society, 1913, 1928, now available online at http://www.sacred-texts.com/jud/loj/index.htm .

3

The 2000 extant inscriptions from the years 1892 to 1941 record the death of more than a dozen young girls.

4

An Inscription of an Esther who is described as having reached old age has not been preserved in the extant

Bagnowka inscriptions; however, nearly 25 inscriptions of other women (and nearly the same for men) record the blessing of old age.

5

See my, "In the Bloodshed of Their Days." Jewish Magazine. January 2010. http://www.jewishmag.co.il/. Images in the Bialystoker Photo Album (David Sohn, editor [New

York, 1951]) reveal women's participation in the organizations noted here and more.

6

In his documentation on the Jewish epitaphs from the former Soviet Union, Michael Nosonovsky noted the use of

two specific verses from the book of Esther in the inscriptions of women named Esther. Esther 2:8 "And Esther was taken to the king's

house" in the inscription of an Esther in the Satanov cemetery in the Khmelitski region, who died in 1788. In this same cemetery an

Esther who passed away in 1634 is connected with the biblical Esther by verse 2:15 "and Esther acquired benevolence". An Esther who

passed away in 1754 is connected with the biblical Esther by the earlier words in Esther 2:15 "And Esther's turn came" in the Buchach

cemetery in the Ternopol Region. Michael Nosonovsky, Hebrew Inscriptions from Ukraine and Former Soviet Union. (Washington,

DC, 2006): 78-79, 89.

7

Following the Rabbinic interpretation of Esther's name rather than its possible Persian meaning of "star".

8

Esther Golda Rozenthal's inscription suggests that she may have been a teacher beyond her home. The first

Jewish-Russian elementary school system was established in Bialystok in 1867, followed by four more elementary schools in 1888, in

which woman may have been allowed to teach. See Sara Bender, Jews of Bialystok During World War II and the Holocaust (Brandeis

University Press, 2008): 12-13.

9

See the Second Targum to Esther 2:7, 9.

10

Early Polish historians of the 1930's described Jewish tombstone epitaphs as 'exaggerated clichés that

have nothing to do with the dead person', 'a Baroque ornament composed from a wreath of words and phrases', 'pompous', and

'overloaded thus hard to understand'. Their reflections may be subjectively harsh for these epitaphs may reflect the hoped for

attributes of the deceased and "the system of values accepted by the Jewish community" in Pre-War Poland. See M. Ba³aban,

Dzielnica ?ydowska. Jei dzieje i zabytki (Lvov, 1909), and Przewodnik po ?ydowskich zabytkach Krakowa

(Cracow, 1935); C. Dawidson, "Epitafia." In Stary cmentarz ?ydowski w £odzi. Dzieje i zabytki. (£odzi,

1938); I. Schiper, Cementarze ?ydowskie w Warszawie. (Warsaw, 1938); and Monika Krajewska, Tribe of Stones:

Jewish Cemeteries in Poland (Warsaw: Polish Scientific Publishers Ltd., 1993), 38.

~~~~~~~

from the January 2010 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|