Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

American Jews and the Congressional Medal of Honor

By Jerry Klinger

Credit falsely given or denied, which is worse… I don’t know.

William Rabinowitz

June 25 and 26, 1876, 263 men of the U.S. Army’s famed 7th Cavalry were led by General George Armstrong Custer to the Little Big Horn River in Montana. In a battle, that has become part of American Wild West legend, Custer faced several thousand Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne Indians. Custer and his immediate command were wiped out, to the last man. The only survivor was a horse named Commanche. Commanche had been wounded, repeatedly. He stood his ground next to the body of his fallen rider, Captain Keogh, who still gripped the horse’s reigns in death. The Indians considered it bad medicine to take a horse that was so closely linked to the dead. The Battle of the Little Big Horn was the American Indian’s last major armed fight for their old way of life. They won the battle but they had lost the war.

Like many young Americans raised in the ethos of the American West, the Battle of the Little Big Horn was a story that excited the blood. It stirred the imagination. What stirred more than the imagination was when I read on the internet about Sergeant George Geiger from Cincinnati, Ohio. He fought at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. He received the Congressional Medal of Honor. Web site after web site told the same fascinating tale. George Geiger was Jewish. My mind raced with excitement at the thought; a Jew had fought at the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

The Battle of the Little Big Horn was actually two battles. Custer, with his bravado and disregard for life and the lives of his men that he had nurtured in the American Civil War, felt confident that his display of American might would cower the Indians into submission with his first assault. He divided his already comparatively modest force into a large unit and a much smaller flanking unit under Major Reno. The two forces were as much as five miles apart when Custer led his men in an assault on the vast assemblage of Indians encamped below him. Quickly, it became apparent the Indians were not going to run in fear or surrender. Custer was pushed back to a nearby hill, aptly named Last Stand Hill. They were overwhelmed. Major Reno did not order his men to come to Custer’s aide. They formed a defensive perimeter and waited for the Indians.

The weather was hot and dry that day. Water was in short supply. The nearest water for the men under Reno’s command was a small stream below them, dangerously exposed to the Indians. They needed water desperately. Eleven men volunteered to run the gauntlet of death to get water for the others. Four men, the best marksmen that Reno had, volunteered to offer covering fire. As the eleven men raced to get water, the four marksmen stood, fully exposed to the Indian assaults. They provided deadly covering fire for the water carriers. For twenty minutes they stood, amidst arrows and bullets, protecting the water carriers, constantly firing at the Indians. The sharpshooters kept the Indians at bay. The water carriers returned safely, not one was injured. The four sharpshooters on the hill who had risked their lives so brazenly to save the rest, they too, were unhurt. Reno’s unit escaped the deadly grasp of the Indians.

One of the four men who stood so bravely on the hill was Sergeant George Geiger. He and the others were awarded the American Congressional Medal of Honor (CMOH), the highest recognition of heroism that the U.S. Government had to offer.

Everyone recognizes George Geiger as a Jewish American for his heroism that day except for the National Museum of American Jewish Military History in Washington. Located in the basement of the Jewish War Veterans of America’s building on R Street, is a museum to America’s Jewish fighting men and women. In the Museum is a Hall of Heroes. The Hall proudly exhibits a short biography and a copy of the citation to the 14 American Jews awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

http://www.nmajmh.org/exhibitions/catalog-hallOfHeroes/cat9.php

Benjamin Levy was the first American Jew to be awarded the newly created CMOH during the Civil War. He was a drummer boy who stood firm holding the battle flag of his regiment in the terrible fighting outside of Richmond in the 1862 failed Peninsula Campaign. He had picked up the fallen regimental flag, exposing himself to enemy fire. His effort permitted his unit to form a new battle line. His heroism saved his regiment from destruction.

http://www.jewishmag.com/111mag/benjlevy/benjlevy.htm

The most recent Jewish American to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor was a Hungarian Holocaust refugee and immigrant, Corporal Tibor Ruben, for action during the Korean War. His citation read:

Citation: For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty: Corporal Tibor Rubin distinguished himself by extraordinary heroism during the period from July 23, 1950, to April 20, 1953, while serving as a rifleman with Company I, 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division in the Republic of Korea. While his unit was retreating to the Pusan Perimeter, Corporal Rubin was assigned to stay behind to keep open the vital Taegu-Pusan Road link used by his withdrawing unit. During the ensuing battle, overwhelming numbers of North Korean troops assaulted a hill defended solely by Corporal Rubin. He inflicted a staggering number of casualties on the attacking force during his personal 24-hour battle, single-handedly slowing the enemy advance and allowing the 8th Cavalry Regiment to complete its withdrawal successfully. Following the breakout from the Pusan Perimeter, the 8th Cavalry Regiment proceeded northward and advanced into North Korea. During the advance, he helped capture several hundred North Korean soldiers.

On October 30, 1950, Chinese forces attacked his unit at Unsan, North Korea, during a massive nighttime assault. That night and throughout the next day, he manned a .30 caliber machine gun at the south end of the unit's line after three previous gunners became casualties. He continued to man his machine gun until his ammunition was exhausted. His determined stand slowed the pace of the enemy advance in his sector, permitting the remnants of his unit to retreat southward. As the battle raged, Corporal Rubin was severely wounded and captured by the Chinese. Choosing to remain in the prison camp despite offers from the Chinese to return him to his native Hungary, Corporal Rubin disregarded his own personal safety and immediately began sneaking out of the camp at night in search of food for his comrades. Breaking into enemy food storehouses and gardens, he risked certain torture or death if caught. Corporal Rubin provided not only food to the starving soldiers, but also desperately needed medical care and moral support for the sick and wounded of the P O W camp. His brave, selfless efforts were directly attributed to saving the lives of as many as forty of his fellow prisoners. Corporal Rubin's gallant actions in close contact with the enemy and unyielding courage and bravery while a prisoner of war are in the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself and the United States Army.

More than fifty years later, President George Bush presented Rubin with the Congressional Medal of Honor, September 23, 2005. The U.S. Army’s refusal to admit to anti-Semitism in its ranks had denied Rubin his recognition for all those years. Two of his commanding officers had recommended Rubin for the CMOH but were killed in action. They began the process that was deliberately impeded by Rubin’s sergeant, Atice V. Watson. Some of Rubin’s fellow GIs were present when Watson was ordered to submit the paperwork for the medal. They were all convinced that Watson deliberately ignored the orders. "I really believe, in my heart, that First Sergeant Watson would have jeopardized his own safety rather than assist in any way whatsoever in the awarding of the medal to a person of Jewish descent," wrote Corporal Harold Speakman in a notarized affidavit.”

The awarding of the CMOH has a time period within which the paperwork is to be processed. As has happened with other American ethnic groups in the U.S. Military, Black, Hispanic and Japanese, special legislation had to be passed by the U.S. Congress ordering the Department of Defense to reopen and re-examine its Medal award process for deliberate anti-Semitism. The legislation sponsored by Congressmen Benjamin Gilman (R-N.Y.) and Robert Wexler (D-Florida) became ironically known as the Lenard Kravitz Jewish War Veterans Act. Lenard Kravitz was the Uncle of Lenny Kravitz, the American comedian and entertainer. Lenard had given his life in defense of America during World War II. One hundred and thirty seven Jewish American soldiers’ acts of heroism were ordered to be reconsidered.

Four times, Rubin had been recommended for the Medal of Honor by commanding officers and comrades. He was recommended twice for the Distinguished Service Cross and twice for the Silver Star. Until the Lenard Kravitz Act reopened the issue of discrimination in the U.S. Army medal process, Rubin had been only received two Purple Hearts for being wounded in action and a 100% military disability rating.

Rubin was not alone in the long struggle to be recognized as a Jewish American recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor. It was not always anti-Semitism that blocked recognition. Sometimes it was much simpler, military bureaucracy and regulations.

During World War II, Captain Benjamin Salomon was assigned to the 2nd Battalion, 105th Regiment, 27th Infantry Division during the invasion of Japanese held Saipan. He was a Dentist. His medical unit was located less than 100 yards behind the American lines when the Japanese attacked. The medical doctor was wounded. Salomon, though trained as a Dentist, became the medical doctor in the crisis. His citation for the Congressional Medal of Honor read:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty:

Captain Ben L. Salomon was serving at Saipan, in the Marianas Islands on July 7, 1944, as the Surgeon for the 2d Battalion, 105th Infantry Regiment, 27th Infantry Division. The Regiment's 1st and 2d Battalions were attacked by an overwhelming force estimated between 3,000 and 5,000 Japanese soldiers. It was one of the largest attacks attempted in the Pacific Theater during World War II. Although both units fought furiously, the enemy soon penetrated the Battalions' combined perimeter and inflicted overwhelming casualties. In the first minutes of the attack, approximately 30 wounded soldiers walked, crawled, or were carried into Captain Salomon's aid station, and the small tent soon filled with wounded men. As the perimeter began to be overrun, it became increasingly difficult for Captain Salomon to work on the wounded. He then saw a Japanese soldier bayoneting one of the wounded soldiers lying near the tent.

Firing from a squatting position, Captain Salomon quickly killed the enemy soldier. Then, as he turned his attention back to the wounded, two more Japanese soldiers appeared in the front entrance of the tent. As these enemy soldiers were killed, four more crawled under the tent walls. Rushing them, Captain Salomon kicked the knife out of the hand of one, shot another, and bayoneted a third. Captain Salomon butted the fourth enemy soldier in the stomach and a wounded comrade then shot and killed the enemy soldier. Realizing the gravity of the situation, Captain Salomon ordered the wounded to make their way as best they could back to the regimental aid station, while he attempted to hold off the enemy until they were clear. Captain Salomon then grabbed a rifle from one of the wounded and rushed out of the tent. After four men were killed while manning a machine gun, Captain Salomon took control of it. When his body was later found, 98 dead enemy soldiers were piled in front of his position. Captain Salomon's extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army.

Delays in submitting the necessary paperwork caused the recommendation for awarding Captain Salomon the CMOH to lapse in the early 1950’s. A second issue was that, technically, Captain Salomon was a medical officer and could not be recognized for his aggressive defense of his position and his patients as if he were a regular combat officer. Repeated efforts by Christian and Jewish officers to have his situation reexamined were declined by the military.

Congressman Brad Sherman of California took particular interest in the failure to honor Captain Salomon. May 1, 2002, in a White House ceremony, Captain Benjamin L. Salomon was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor by President George Bush.

Anti-Semitism was a factor in the consideration of recognition of American Jews and their military contributions. During the American Civil War, it was not uncommon for Jews to not admit to being Jewish. In some situations, if a Jewish soldier were wounded, he might be amongst the last evacuated for medical treatment. Many sources identify Henry Heller, a recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor for heroism during the battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia, as Jewish. The National Museum of American Jewish Military History in Washington does not.

The Museum does not recognize Henry Heller as Jewish because there is insufficient evidence to verify if in fact he was Jewish. Heller is buried in the Kings Creek Baptist Church Cemetery, Kingscreek, Ohio. Being buried in a Christian cemetery is seemingly good evidence that an individual was not Jewish. However, it is not conclusive. Heller could have been married to a non-Jew. He could have converted. He could have died and there were no Jewish cemeteries to bury him in. Or he simply did not care.

Sergeant John Levitow was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. He is recognized by the National Museum of American Jewish Military History as Jewish.

Sergeant Levitow’s Citation reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. Sgt. Levitow (then A1c.), U.S. Air Force, distinguished himself by exceptional heroism while assigned as a loadmaster aboard an AC-47 aircraft flying a night mission in support of Long Binh Army post. Sgt. Levitow's aircraft was struck by a hostile mortar round. The resulting explosion ripped a hole 2 feet in diameter through the wing and fragments made over 3,500 holes in the fuselage. All occupants of the cargo compartment were wounded and helplessly slammed against the floor and fuselage. The explosion tore an activated flare from the grasp of a crewmember who had been launching flares to provide illumination for Army ground troops engaged in combat. Sgt. Levitow, though stunned by the concussion of the blast and suffering from over 40 fragment wounds in the back and legs, staggered to his feet and turned to assist the man nearest to him who had been knocked down and was bleeding heavily. As he was moving his wounded comrade forward and away from the opened cargo compartment door, he saw the smoking flare ahead of him in the aisle. Realizing the danger involved and completely disregarding his own wounds, Sgt. Levitow started toward the burning flare.

The aircraft was partially out of control and the flare was rolling wildly from side to side. Sgt. Levitow struggled forward despite the loss of blood from his many wounds and the partial loss of feeling in his right leg. Unable to grasp the rolling flare with his hands, he threw himself bodily upon the burning flare. Hugging the deadly device to his body, he dragged himself back to the rear of the aircraft and hurled the flare through the open cargo door. At that instant the flare separated and ignited in the air, but clear of the aircraft. Sgt. Levitow, by his selfless and heroic actions, saved the aircraft and its entire crew from certain death and destruction. Sgt. Levitow's gallantry, his profound concern for his fellowmen, at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Air Force and reflect great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of his country.

He is buried under a Cross. Sergeant Levitow was a member of the Jewish War Veterans of America and associated his identity with them. When he died, Levitow’s wife, who was not Jewish, wanted him to be buried with a Cross on his grave.

During World War II Major General Maurice Rose served under General George Patton. Rose was one of the finest tank commanders in the American army. He is frequently credited with many of General Patton’s successes. General Rose was the highest ranking Jewish officer in the U.S. Army to die in action. During his military career, General Rose refused to be officially recognized as Jewish because of his concern that his Jewishness would be a problem for career advancement. When he was killed in combat, he had not designated a religious preference. Controversially, his non-Jewish wife insisted he had converted. Major General Maurice Rose, the son and grandson of Rabbis, was buried under a Cross.

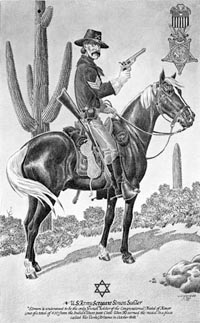

Simon Suhler, a Jewish German immigrant, served in 4th New York Heavy Artillery during the Civil War. He was honorably discharged. Suhler reenlisted under an alias Charles Gardner, keeping his Jewish identity secret because of anti-Semitism in the military. He was posted, as part of the 8th Cavalry, to Arizona as an Army Scout. Indian Wars with the Apaches were raging. Between August and October 1868, Suhler repeatedly exposed himself to extreme risk for his command and comrades. He was awarded the CMOH for his meritorious service still using the name, Charles Gardner. He died May 15, 1895 and was buried in the San Antonio Military Cemetery. Ninety three years later, a distant family member came across previously unknown records about him. The records confirmed that he was Jewish and that he had served his country under a false name. In 1988, the U.S. Army changed his tombstone to read – Simon Suhler, Medal of Honor, New York, Co 1, 4 U.S. Arty.

Sergeant George Geiger is not recognized by the Jewish War Veterans’, National Museum of American Jewish Military History, as being Jewish. They cannot verify his Jewish identity though many different web sources and a few books emphatically identify him as Jewish.

Being concerned about the disagreement, I investigated George Geiger’s records. I wanted to prove that he was Jewish. I wanted to prove that a Jew had won the Congressional Medal of Honor for meritorious service at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Researching, I located his Army Pension records and his medical records from when he admitted to the Dayton, Ohio Veteran’s Hospital in 1899. Under religion, for both his pension records and Army military history records at the hospital, his religion was clearly listed as Protestant.

He was married, but no name was given. His next of kin was a step-brother, Edward Metzger from Cincinnati. Metzger could be a Jewish name and then it might not. Geiger may be Jewish and then he may not. Geiger might have started out as a Jew and ended his life wanting to be a Protestant. The most likely situation is he was never Jewish. The sources on the net, the books that have been written are wrong. The National Museum of American Jewish Military History is correct.

Even without George Geiger as a member of the tribe, American Jewish fighting men and women have a long, distinguished history. Today, it is well known that American Jews have been and are honored members of the American Armed Forces. Anti-Semitism may still exist, but it is not tolerated or condoned.

Who is a Jew? Is a Jew still a Jew if they marry a non-Jew? Is a Jew still a Jew if they are buried in a non-Jewish cemetery under a Cross? Is a Jew still a Jew even if they never claim to be Jewish? Is a Jew a Jew is they have not renounced their Judaism or converted? What does it mean to be a Jew, or not, in the face of bigotry and risk?

The answer for a lot of brave Americans was not easy. For those of us not faced with the question, it is even more difficult.

Jerry Klinger is President of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation

www.Jashp.org

jashp1@msn.com

* * * * *

For more articles on Contemporary Jewish History, see our Contemporary Jewish History Archives

~~~~~~~

from the July 2011 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|