Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

“What

a thunderous voice!”

Remembering

Pesach Kaplan

Heidi

M. Szpek, Ph.D.

“In

the year 1915, in the midst of the German Occupation, I just finished

translating all of Krylov’s fables. … At that time,

although Bialystok was the most open-minded city in the entire world,

there were no functioning publishers. Yet in Bialystok a cultural

revolution was still underway, which allowed my translation of

Krylov’s fables to be published.”

So wrote Pesach Kaplan in the Preface to his Yiddish translation of

the fables of Ivan Krylov, entitled Krylov’s

Moshelim.

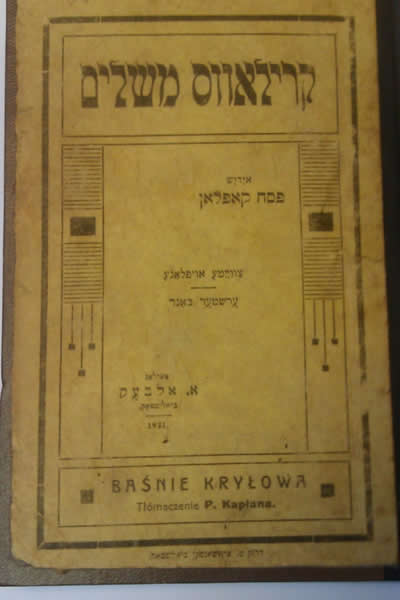

Image

2 Krylov’s

Moshelim

Pesach

Kaplan was a prominent figure in the history of Jewish Bialystok.

Born in 1870 in the shtetl

of Stavisk, west of Bialystok, Kaplan’s father served as a

cantor and ritual slaughterer. From age 13 until 19, Kaplan moved

with his father from town to town, studying in yeshivas until his

family finally arrived in Warsaw. In Warsaw, Kaplan was introduced

to the Haskalah,

engendering his love of Hebrew language, literature and the Jewish

enlightenment. Coupled with his Talmudic training, these interests

found an outlet in writing and his initial advocacy of Zionism. In

1888, Kaplan moved to Bialystok where writing became a daily

endeavor. In Pinkos

Bialystok

(Chronicle of Bialystok), author Abraham Samuel Herszberg emphasized

Kaplan’s literary and community contributions to Bialystok.

Kaplan was a teacher, a journalist, a writer and much more. He

served on the Relief Committee of the Teachers’ Union after the

1906 Pogrom, as a member of Bialystok’s kehillah

from 1918-1928, and in 1919, Kaplan founded the daily Yiddish

newspaper Dos

Naje Lebn

(later renamed Unzer

Lebn),

serving as its editor-in-chief until 1939. For his extensive

literary contributions perhaps Kaplan is best known. Indeed,

Herszberg expresses his indebtedness to Kaplan’s extensive

publications as a source for his own writing of Pinkos

Bialystok.

Yet

there is another role for which Kaplan is also remembered. During

World War II and the Holocaust, when the Bialystok Ghetto was

created, Kaplan became a member of the Judenrat.

As a teacher he became the head of the Bialystok Ghetto’s

Education Department. Within the forced confines of the ghetto,

Kaplan believed education and cultural activities were essential,

serving both as a sign of resistance amidst oppression and preserving

the future of Jewish tradition. In response to the Aktion

of July 1941 in Bialystok, Kaplan is also well-known for his moving

poem Rivkele

the Sabbath Widow,

which allowed him to express both the pain and hope of the wives and

children whose husbands and fathers had been taken away, never to

return. In March 1943, Pesach Kaplan died in the Bialystok Ghetto,

having witnessed the beginning of Ghetto’s liquidation in

February. During his years in the Bialystok Ghetto, Kaplan continued

his writing in the form of two diaries, today preserved in the

archives of Yad Vashem.

A

chance discovery on Ebay of a book by Pesach Kaplan revealed to me

yet another side of Pesach Kaplan. His name had captured my

attention before the title of the book. Only several weeks later,

when the book arrived, did I – with initial disappointment,

learn that this volume was a translation project by Kaplan and not

poetry of his own writing. Disappointment gave way to intrigue when

I realized the import of this work – Krylov’s

Moshelim

“The Fables of Krylov”. Ivan Andreyevich Krylov rose to

be become a prominent Russian writer and intellectual of the late

18th

and early 19th

centuries. His fables, following in the tradition of Aesop and La

Fontaine, brought him to literary prominence. The animals in his

fables provided legendary insight into caricatures of Russian

society; the stories and their morals served as satire to disguise

Krylov’s disdain for Russian repression.

Yet

why did Pesach Kaplan devote such energy to this translation project,

especially amidst the turmoil of World War I? Bialystok was then

part of Russia; Russian language, culture and politics clearly

impacted this city’s inhabitants regardless of their

inclinations. In the Preface to Krylov’s

Moshelim,

Kaplan offers his explanation: “In the year 1914, the idea was

borne, to create for Jewish children, likewise for the general adult

reader, a new translation of Krylov’s Fables.”

Apparently, an older Yiddish translation by Zvi Hirsh Reichson,

containing only a small portion of the hundreds of Krylov’s

fables was insufficient. Kaplan, advocate of the Haskalah,

found value in the secular literature of Russia for Jewish youth and

community alike. Encouraged by his friend in the Bialystok Literary

Circle – perhaps the same friend, Aharon Albek, who wrote the

Forward to this volume, Kaplan undertook this project at what would

seem a most unpropitious moment – amidst the First World War.

At a time “when there were no active publishers”, Kaplan

found a publishing house – A. Albek’s, and a printing

shop – Pruzszanski’s on Lipowa Street in Bialystok.

Kaplan initially planned to publish a five volume set of all of

Krylov’s fables translated by himself into Yiddish, “except”

– as Kaplan wrote, “for a few fables, which were not

translatable in his opinion.” Kaplan’s five volume

project was revised (as he noted) into a three volume set. The book

I had procured was the first volume, containing 67 fables. There are

familiar fables in this volume, found likewise in many translations

to this day – The Crow and the Fox, The Wolf and the Little

Sheep, Two Doves, The Rooster and the Pearl, The Stone and the Snake,

and The Elephant and the Mouse. This type of fable predominates in my

collection. Such fables offer classic caricatures of Russian

individuals of Krylov’s day through the guise of animals.

There are other fables in this collection, such as The Musicians, The

Voyage, The Imperialist, The Three Lady Killers, The Heretics, The

Funeral, The Householder and the Speculative Thinker, which also

offer insight into Russian society and life without engaging

characters from the animal kingdom!

When

Kaplan translated these fables from Russian into Yiddish he set in

place two particular rules: 1.) that the naiveté, folksy and

concise style of Krylov be maintained; and 2.) that individual

phrases and larger “pictorials”, as well as general

features of the fable, must not appear strange to the Yiddish reader.

Kaplan was undertaking an energetic translation project, desiring

to maintain the integrity of the Russian literary style yet demanding

that the Yiddish translation would appropriately “feel

Yiddish”! To this end, Kaplan wrote in his Preface, he would

permit himself to “work-over” a fable to maintain its

substance as well as its moral. In the end, Kaplan believed he

offered “a pure translation, which reverberates with the

classical veracity of the [original] poet.”

My

eye was not drawn to the popular animal fables in this volume, nor to

those without animal characters, nor even to three tempting poems,

entitled “Abraham’s Soup”, “Elijah the

Prophet and the Beggar” and “Samson”. I was

immediately draw to the fable entitled “Der

Magid”

– The Preacher:

There

stands a magid

on the bimah

And

he delivers a spirited sermon (droshe),

He

equates the artistry of men with dust-rubble (rimah),

And

he chastises and flays the wicked (roshe).

Sparks

spritz forth from his mouth (moyl)

Every

word a more zealous bullet (koyl).

Because

of his speech a shiver goes through each body (lajber),

So

that not only cry out the God-fearing women (wajber).

Indeed,

for a long time the magid

does not struggle (kemfn)

in

resolving the disputes for deeper meaning (kremfn).

Then

a lament suddenly breaks out (oijs)

in

the synagogue, the magid’s

sermon is so grand (grojs).

But

after the sermon everyone stands still (shtajn)

Astonished

because of the magid’s

Godly-gifts (Elokim).

What

a thunderous voice (shtim)!

Each

example like a little pearl or a beam of light (shajn)!

Even

a stone is able to feel! (vern)

Like

magic, tears burst forth (trern).

Only

one person stands in the corner (winkl)

But

– no spark is in his eye (finkl).

A

neighbor says to him: What’s wrong with you? (mayr)

I

see not even one eye has yet a single tear! (trayr)

Was

the interpretation too difficult for your mind? (shvayr)

But

why do I not cry as you all do? I’m just not from the

kehillah!

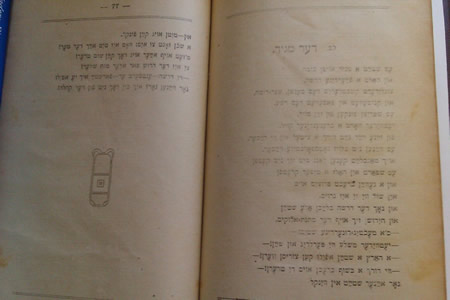

Image

3 Kaplan’s translation of Der

Magid

In

this rough translation (that bears no claim to the brilliance of

Kaplan’s translation from the Russian and acknowledges the

difficulties of several older Yiddish variants in spelling!), I was

first struck by specific words. Magid,

bimah,

droshe,

Elokim,

and kehillah

clearly were directed at Kaplan’s early 20th

century Yiddish audience. The pattern of rhyme is equally

intriguing: bimah,

droshe

//

rimah,

roshe;

moyl//koyl;

layber//wayber

… ababccddeeff. The pattern is repeated until all but the

last five lines: a’b’a’b’c’c’d’d’e’e’f’f’f’g’

– a.

The rhyme of mayr/trayr/shvayr

slows the reader as the questioning of the tearless man begins. The

tearless man begins to offer his response, slowed again by the

unrhymed Yiddish line (apyilu),

to be followed by the punch line: “I’m just not from the

kehillah!” With this final line, ending in kehillah,

rhyme is restored back to the opening words bimah

and rimah.

Krylov was known for his rhyme; Kaplan clearly captured the rhyme

for his Yiddish audience, preserving the classical integrity of

Krylov as he had promised.

I’ve

chanced upon an English translation of this fable by C. Coxwell

(1920). Intriguing, however, is its title – “The

Parishioner”. The focus, as the title suggests, is on the

‘parishioner’; though the eloquence of the pastor is

noted as in the Yiddish translation:

Once,

in a church, a pastor,

Who looked on Plato as of eloquence a

master.

Discoursed, before his flock, concerning worthy

deeds.

A speech mellifluous, of perfect form, proceeds

To treat of

purest truths with art appearing artless.

As by a golden chain.

To heaven are lifted thoughts of hearers even heartless,

And

all perceive the world is full of projects vain.

The orator has

finished preaching.

And yet his listeners stay, being to glorious

skies

Borne by the magic power of wondrous, lofty

teaching,

While pearly drops, escaping, flood their eyes.

And now the

congregation leaves the temple holy,

"How I his gifts

admire!"

Says one man to the next, in modest tone and

lowly,

"What sweetness, touched with fire!

Such richness

every heart to virtue has deflected;

But, neighbour, you by it

but little seem

affected.

Your cheek displays, methinks, no single

tear,

Have you not understood ?" "Yes, entertain no

fear!

But, with this parish, and folk here,

I, Sir, in no way am

connected."

In

yet another English translation by I. Henry Harrison (1883), this

fable once again entitled “The Parishioner”, affirms the

Russian title. Harrison also offers a chronology and classification

of Krylov’s fables. “The Parishioner”, written in

1825, is situated among the later years of Krylov’s composition

of fables (1806-1836). It is classified as a personal fable intended

to depict the cliques among writers and, in particular, how Krylov

felt excluded from such groups. Harrison translates an opening

stanza to this fable, rendered by neither Kaplan nor Coxwell, which

depicts Krylov’s feeling of exclusion:

“Many

there are, be only once their friend,

And

thou the first of writers art, a genius without end;

But

let another come,

However

sweetly he may sing, they’re dumb;

Not

only can he not the slightest praise expect,

They

fear to feel the beauties they detect,

And,

though I may annoy them by the act,

I

here shall tell no fable, but a fact.”

Krylov,

it would seem, was the first of writers, the genius –

represented in the fable’s eloquent “pastor”, to

whom presumably a writer from another clique (“the neighbor”)

would offer no praise nor shed a tear. This opening stanza offers

much insight into the intended meaning of this fable – so why

would Kaplan (and Coxwell) exclude it from translation?

No

translation is a perfect transference of an original composition.

Kaplan wrote in his Preface that he would permit himself to

“work-over” a fable to maintain its substance as well as

its moral without detriment to the classical integrity of the author

or the relevance of the fable’s new Yiddish audience.

Kaplan’s translation does preserve the general substance of

Krylov’s poem and indeed matches Krylov’s attention to

rhyme. However, Kaplan also “worked-over” this fable to

bring more emphasis to the magid,

the depth of the magid’s

droshe

(sermon), with which the magid

engaged the text and audience – perhaps a reminder of Kaplan’s

years in the yeshivas throughout northeastern Poland, and the impact

of this teaching on the congregation – again perhaps a reminder

of the impact Kaplan’s teachers had upon him. Omitting the

opening stanza was thus essential to redirect this fable to a Jewish

audience (and apparently also for Coxwell’s audience). Neither

Kaplan nor Coxwell wished to ponder a writer’s exclusion from

literary guilds, rather they saw in this fable another meaning –

perhaps that the eloquence of a magid

or pastor is dependent on his connection to a particular community.

Perhaps the master-student relationship is essential for truly

appreciating the droshe

(sermon). For this reason omission of the opening stanza was

essential.

The

first time I read Kaplan’s translation, however, my thoughts

were immediately drawn to a detail by which, at least for me, Kaplan

transformed this fable for the Yiddish world – by delivery of

the punch line! Krylov’s neighbor delivers his line with a

haughty air as suggested by Coxwell’s translation (“But,

with this parish, and folk here, I, Sir, in no way am connected.")

and even in Harrison’s earlier translation (“But then,

what cause for me to cry? I am not of this parish, I!”). I

imagine Krylov’s ‘tearless man’ in these

translations abruptly walking away. Such a punch line accords well

with the master fabulist Krylov’s personal intention for this

fable. But for Kaplan’s ‘tearless man’, I

envision him offering a whimsical shrug, tilting his head with a nod

as he responds – “I’m just not from the kehillah!”

… and off he goes. Kaplan is indeed renowned for his literary

and community contributions and the sad fate that stole his life in

the ghetto. Yet discovery of this volume, with attention to just one

poem, suggests that there is even more to be learned about the voice

of this extraordinary man. Beneath Kaplan’s silvery coiffure

and stern countenance, there lurks a man who could also deliver a

good dose of Yiddish humor!

Photo

Credits: Image

1 David Sohn, Bialystok

Photo Album;

Image 2, 3 Heidi M. Szpek.

Sources:

Pesach

Kaplan, trans., Krylovs

Moshelim. Bialystok:

A. Albek, 1921.

David,

Sohn, ed., Byalistok

bilder album fun a barimter shtot un yire yiden yiber der welt.

[Białystok Photo Album of a Renowned City and its Jews the World

Over.] New York, 1951.

“Stawiski

Yizkor Book.”

http://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/stawiski/sta043.html

“Bialystok

Yizkor Book.” http://www.zchor.org/bialystok/yizkor7.htm#death

Sara

Bender, Jewish

Białystok during World War II and the Holocaust.

Waltham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2008.

Herszberg,

Abraham Samuel, Pinkes

Byalistok [Pinkos

(The Chronicle of) Białystok.]

Volumes I and II. New York: Białystok Jewish Historical

Association, 1949-1950.

C.

Fillingham Coxwell, trans., Kriloff’s

Fables. London: Kegan

Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd, 1920.

I.

Henry Harrison, trans., Kriloff’s

Original Fables.

London: Remington & Co., 1883.

Heidi

M. Szpek, Ph.D. is Chair and Associate Professor in the Department of

Philosophy & Religious Studies at Central Washington University

(Ellensburg, Washington), currently writing a book on the Jewish

epitaphs from Bialystok, Poland. Her most recent journal articles on

Jewish epitaphs include “Jewish Epitaphs from Bialystok,

1905-6: Mending the Torn Thread of Memory.” East European

Jewish Affairs. Vol. 41, Nos. 1–2, April–August 2011,

1–23, and “Filial Piety in Jewish Epitaphs.” The

International Journal of the Humanities.

Volume 8.4 (2010): 183-202. She has also contributed a variety of

articles on Jewish epitaphs and Jewish material culture in

northeastern Poland to The Jewish Magazine online. Her website is

www.cwu.edu/~szpekh

~~~~~~~

from the August 2011 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|