Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

Goebbels, Culture and Propaganda

By Peter Bjel

Joseph Goebbels was the first to see the potential

of fusing art, culture and the Nazi state. Hitler so wished this

merging, and so came to pass the transmission of Nazi ideology

through art and culture. This is the second of three articles.

Given his

own intellectual and academic background, cultural and artistic

things intrigued the Third Reich’s Propaganda Minister, Joseph

Goebbels. It was almost certainly by this that he seized on the

dissemination-potential that cultural outlets could serve in

propagating Nazi ideology – but also on the potency of culture

in fomenting dissent. “Goebbels was an impresario of genius,

the first man to realize the full potentialities of mass media for

political purposes in a dynamic totalitarian state.”1

Not everyone within the Nazi hierarchy agreed with the prospect of

fusing art, culture and the Nazi state together, notably Alfred

Rosenberg, with whom Goebbels would have a lengthy rivalry that would

emerge between and within their respective ministries.

Goebbels

won out, in the end, because Hitler so wished this convergence. “Yet

this was exactly what Hitler wanted: a fusion of politics,

propaganda, and art. He considered politics to be the greatest of

all arts, and propaganda the most important arm of politics. And

Goebbels was in full agreement with Hitler…”2

At the end

of November 1933, a Reich Chamber of Culture was unleashed, and

Goebbels allied himself with Robert Ley, who had been the Nazi

Economics Minister, in creating an organization known as ‘Strength

through Joy,’ which served to undermine the likes of

Rosenberg’s cultural opinions while channelling and branching

out more power to Goebbels. With so much power centred on Goebbels,

there were reasons for satisfaction. “With this power, he could

‘mobilize the spirit’ in the people for Hitler’s

policy of foreign expansion.”3

Once war broke out in September 1939, these cultural conduits would

be contoured to fit the ideological and circumstantial needs of the

time. By way of cultural spheres, Nazi influence was all

encompassing, covering film and theatre, literature, visual art and

the presses, as well as radio programming and music. These spheres

shall all be considered in turn.

* * *

On film

(and, perhaps, to a lesser extent, the theatre), Goebbels advised

against making any overtly propagandistic feature, out of concern

that its abruptness would simply turn people away, closed-minded.

“More than all other forms of art, the film must be popular in

the best sense of the word,” he declared. “Nor must it

lose its strong inner connection with the people. Films should be

strictly contemporary in spirit even when dealing with subjects set

in the past; once they achieve this quality they will bridge the

nations and become the ‘spokesmen for our age.’”4

To achieve this, Goebbels stood poised to provide state-backed

incentives and capacities for filmmakers to hold a degree of creative

independence.

A few

films were concerned with overtly propagandist themes, though

Goebbels took care to not carry this on excessively; all of these

things notwithstanding, the German film industry under Hitler and

Goebbels wound up suffering from a creative ‘brain-drain,’

whereby many of the country’s most talented filmmakers and

directors – Fritz Lang is a great example – were forced

into temporary or permanent exile abroad.5

Akin to one of his propaganda principles, Goebbels spent much time

observing foreign-made films, even after 1939. American films he was

especially keen on studying, and he went to great lengths to acquire

copies of them. “The press attaches in German embassies in

Sweden, Switzerland and Portugal were under orders to get hold of

prints of American films and have them illicitly copied for him.”6

Under Hitler and Goebbels, many of

Germany’s most talented filmmakers, like Fritz

Lang, were forced into temporary or permanent exile

abroad.

Reflecting

on the subtlety that was the working rule for most Nazi-era films,

Eric Rentschler writes that the Third Reich’s film industry was

a product of “more than anything, a Ministry of Illusion,”

and that “The customary tropes of the uncanny and horrendous do

not accurately characterize the vast majority of the epoch’s

films, light and frothy entertainments set in urbane surroundings and

cozy circles, places where one never sees a swastika or hears a ‘Sieg

Heil.’”7

Yet there remained a sinister motive behind film, and it was that

“Goebbels endeavoured to maximize film’s seductive

potential, to cloak Party priorities in alluring cinematic shapes, to

aestheticize politics in order to anaesthetize the populace,”

and “German films were to become a crucial means of dominating

people from within, a vehicle to occupy psychic space, a medium of

emotional remote control.”8

By

Rentschler’s count, 86 percent of films churned out during the

Nazi era were of the so-called “unpolitical” variety,

which extolled the banal features of life without signs of the Third

Reich.9

The German revue film, which “shows the civilian troops on

parade, often garbed in uniforms and usually choreographed as a

costumed cadence march,” with its mechanized columns of bodies,

often scantily-clad, had “psychic emotion” prevalent.10

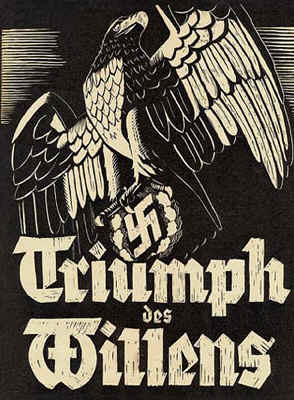

Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph des Willens, released in

1935, and probably one of the most famous films to come out of the

Nazi era, falls into this category. “The masses are allowed to

enter the picture, but only their leaders are allowed to speak.

Hitler himself is the main actor, here celebrating his wedding

fantasies with the masses.”11

It too bears such subtleties, as when it opens with shots from the

high skies, amid clouds, out of which it becomes clear that, from

these ‘high heavens,’ Hitler is descending to Earth (in

his airplane) and to a nation waiting for him with perfect adulation,

as if he were a god.12

Triumph of the Will is probably one of the most famous films to come out of the Nazi era.

The

remaining fourteen percent of films, however, were the exact

opposite; the ways in which they were drawn on real-life and set

ideological themes demonstrated Goebbels’ system of mythmaking

at work. Thus, Hitlerjugend Quex, directed by Hans Steinhoff

and set in the chaotic Weimar period, drew on the murder and

subsequent martyrdom of a certain fifteen year-old Herbert Norkus

who, in January 1932, was stabbed to death by Communists in revenge

for the death of one of their own. Norkus had been out distributing

Nazi pamphlets in a working-class district of Moabit.13

Goebbels

went on a harangue in Der Angriff, detailing the wickedness of

Communist “child-murderers” and the death of Norkus: “The

delicate head is trampled to a bloody pulp. Long, deep wounds go

into the slender body, and a mortal gash penetrates heart and

lungs….Wearily, black night descends. From two glassy eyes

stares the emptiness of death.”14

According

to Jay W. Baird, “The life and death of Herbert Norkus had lent

new credence to the ethos of the Hitler Youth.”15

A novel by Karl Aloys Schenziner, and then a film soon followed his

elaborate state funeral, and Norkus became the character Heini

Voelcker: “It was at once a propaganda and aesthetic success,

an ornament to Goebbels’ dream of utilizing the best of modern

technique in the service of the mythical National Socialist ideal.

Above all, it appealed to youth in a remarkable way. Through both

Party and Ufa [the official Nazi film distribution company]

commercial channels, its audience numbered well over 20,000,000

viewers….As late as 1942 it was being shown in the

Jugendfilmstunden of the Hitler Youth, an important propaganda

activity of the organization.”16

So it was,

in this example, that film, myth, and history were put together and

moulded into one type of Nazi-era film that emanated from Goebbels’

ministry.17

Herbert Norkus (above) and his death in January 1932

was propagated by Goebbels, and became the premise for the film

Hitlerjugend Quex.

When war

broke out in September 1939, the Nazi film ministry began to produce

films that sometimes reflected and ideologically shaded this reality

via films. Thus, for example, the film Ohm Krueger, though it

was set in South Africa during the Boer War, meshed this past setting

with the present war with Britain. The dying and defeated character

Krueger declares that, “Thus England subdued our small nation

by the cruelest means. But the day of judgement will come at last.

I don’t know when, but so much blood cannot have been spilled

in vain. So many tears will not have been shed for nothing. We were

a small and weak nation. But big and powerful nations will stand up

to British tyranny. They will strike against England’s soil.

God will be with them. And then the path will be free for a better

world.”18

The film,

at one point, according to Marcia Klotz, subtly demonizes the British

for having placed Boers in concentration camps, which they had

(indeed) been the first to invent – though it is not, of

course, pointed out that the Germans had quite clearly outdone the

British in this regard at the time Ohm Krueger was released.

Klotz quotes David Hull: “The unbelievable gall of blaming the

invention of concentration camps on the British – whether true

or not – showed Goebbels at the height of his cynicism.”19

In light

of concentration camps, as well as the system at work behind them,

Hitler conducted two parallel wars at the same time: one against what

would become the Allies, and the other on the Jews of Europe, the war

on the latter of which he intensified when he began losing the

former.20

Though evidence of the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question”

never made its way into popular films sanctioned by Goebbels’

ministries, the vicious anti-Semitism which began the evolution of

Nazi-Jewish policy in such a direction, and which was a staple of

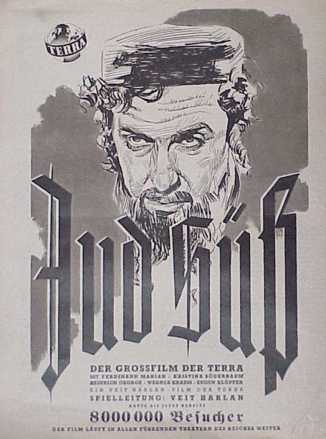

Nazi ideology, did come out. Two of the most infamous films in this

regard were both released in 1940: Franz Hippler’s Der Ewige

Jude, and Veit Harlan’s Jud Suess.

The

former, the title of which means “The Eternal Jew,”

included not-so-subtle depictions of Jews as rats scurrying from a

sewer-grating and infesting all surroundings. At one point, the film

centres on a group of (degenerate-looking) Hasidic Jews, apparently

meant to collectively represent East European Jews as they ‘normally’

are, but then fades to this same group without their beards and

discernible clothes. “The hair, beard, skullcap and kaftan

make the Eastern Jew recognizable to everyone,” the narrator

warns. “Should he remove them, only sharp-eyed people can spot

his racial origins. An essential characteristic of the Jew is that

he always tries to hide his origins when among non-Jews.”21

A similar

cinematic technique is employed in Harlan’s Jud Suess, where

the film’s antagonist Suess-Oppenheimer is introduced in such

appearance, and is last seen at his execution the same way. During

the rest of the film, however, he appears the way the rest of the

German villagers are dressed, further lending credence to the

depictions of his deceit and cunning deviousness.22

The story revolves around the character of Suess-Oppenheimer coming

to the German village of Wuerttemberg, whereby he loans a lot of

money to Duke Karl Alexander; the entire village is in pandemonium

when the Duke, who cannot repay Suess-Oppenheimer, allows other Jews

to move in. A sub-plot also ensues, whereby Suess-Oppenheimer winds

up making advances on the Duke’s daughter, Dorothea and,

supposedly alluding to vampire-like connotations, rapes her while her

husband is being tortured.23

A poster for Veit Harlan’s 1940 film Jew

Suess.

Goebbels’

objective with Harlan’s film was at least partially successful;

more than 20 million viewers saw it, and “It was often screened

in areas where deportations of Jews to concentration camps were

planned, and was shown to SS soldiers before they were ordered to

move against Jews. According to some reports, theatre-goers often

attacked Jews in the streets after viewing the film.”24

According to David Stewart Hull, the other, substantially polished

anti-Semitic film churned out by Goebbels’ ministry was Die

Rothschilds Aktien auf Waterloo, which also came out in 1940; he

described it as “one of the most viciously polished pieces of

propaganda-fiction of the Nazi period.”25

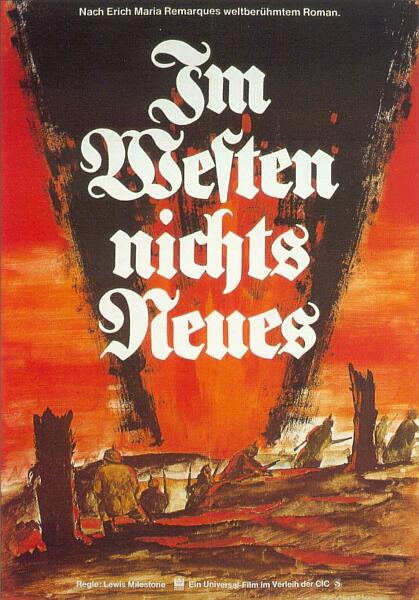

Other

films, as with literature and any other nonstandard manifestations of

culture, were purged or, in some cases, pushed underground. Even as

early as 5 December 1930, this happened when the film adaptation of

Erich Maria Remarque’s 1929 anti-war novel Im Westen nichts

Neues (that is, All Quiet on the Western Front) was shown

at the Mozart cinema. Goebbels subverted it by buying a block of

tickets and distributed them to SA men, whereupon they released mice

and stink bombs in the theatre itself in which it was screened. Six

days later, the Weimar chief film censor banned the film, to which

Goebbels commented: “The film of shame has been banned. With

that action the National Socialist movement has won its fight against

the dirty machinations of the Jews all along the line.”26

Remarque was, in fact, Roman Catholic, but his book, as well

as its sequel Der Weg Zuruck (that is, The Road Back),

published in 1931, was among the many examples of pacifistic

‘un-German’ literature that was incinerated during the

book burnings.27

Erich Maria Remarque (photo) and his famous 1929

book All Quiet on the Western Front which was made into a film (poster) one

year later, were all attacked by the Nazis.

The

German theatre bore a similar fate of forced ideological

Nazification, as when Max Reinhardt’s Deutsches Theater Berlin

was gradually incorporated into the Reich Theatre Chamber, another

offshoot of the Cultural Ministry, and became an outlet for the

types of theatrical performances Goebbels permitted. “During

the fourteen months that had elapsed since the exile of Max

Reinhardt, the theatre had lost not only its owner, but also its

repertoire, its regular audience, and many members of its famed

ensemble.”28

In 1935,

after the death of Theatre Chamber President Otto Laubinger,

Goebbels succeeded in reining in the theatres to his Ministry, first

by purging its officials of Jews and (alleged) Communists, then by

setting out ideologically fit productions to be performed, and

instituting rigorous personnel filtration schemes, such as entrance

examinations and background checks for those wishing to become

involved in the theatre.29

Goebbels’ tactics on the theatres were successful in large

part because of theatre personnel: “It was their own

susceptibility to various forms of seduction that allowed German

theatre people to play an important supporting role in the Third

Reich,” especially through the “multifaceted patronage

of the theatre establishment.”30

In the

fields of visual art, literature and the press, the same techniques

of creativity interspersed with ideological enforcement were

undertaken. Visual artists, like their filmmaker counterparts, were

forced to flee abroad or cease their activities, while the industry

and the art itself that had been crafted pre-1933 underwent purges.

“The purge of modern art was not, however, limited to the art

produced by Jewish, foreign, or Communist artists. Whatever the

Nazis claimed undermined ‘desirable’ aesthetic, social,

cultural, or political values, or physical or racial ideals, was to

be eliminated from German society; this included all the modern

movements, such as Expressionism, Cubism, Futurism, Constructivism,

and Dada.”31

Hitler’s

pronouncements on permissible and impermissible art effectively

decimated this creativity in Germany. It can also be read as a

microcosm of fascism itself. “Firmly believing that culture

is the cornerstone of any enduring society, Hitler recognized that

art must play a major role in the building of his ideal German

nation. He articulated the goals of what he considered true German

art: it must develop from the collective soul of the people and

express its identity; it must be national, not international; it

must be comprehensive to the people; it must not be a passing fad,

but strive to be eternal; it must be positive, not critical of

society; it must be elevating, and represent the good, the

beautiful, and the healthy.”32

Literature

and literary control was one of the few fields in which Goebbels’

rival, Rosenberg, won out over jurisdiction and authority via the

‘Amt Shrifttumspflege,’ an office endowed with the

mandate to, once again, propagate National Socialism. “The

Amt’s activities were, therefore, focused on three

objectives: the evaluation of current German literature, the

promotion of these books found to be ideologically compatible with

National Socialist doctrines, and the control and supervision of

literature with the Party at the Gau and Kreis levels.”33

Akin to

what was happening elsewhere in cultural matters under Nazi control

and supervision, the obvious quality and output declined

drastically, as Herbert P. Rothfeder points out: “Books which

received positive evaluations were generally those which correctly

extolled National Socialist doctrine, glorified Germanic virtue, or

demonstrated the inherent superiority of the Nordic race over the

remainder of Europe. Technical and scholarly works [!] were judged

primarily on their proper interpretation of National Socialist

ideology rather than on their factual content.”34

A system of literary façade joined the ranks of Nazi

culture, whereby one German evaluator of literature quipped, “The

typical Nazi author always tried to cover up his lack of ideas…by

a spate of words which sounded impressive and meant nothing.”35

Rothfeder

notes, revealingly, that out of fear of provoking a powerful

institution as the Roman Catholic Church (the influence of which

still resonated widely among the German population), this was the

only zone in which literary control and censorship had “absolutely

no effect.” Banned books written by taboo authors as Heinrich

Heine, Theodor Herzl, Emil Ludwig and Karl Marx, could still be

found and read in Nazi Germany.36

This was

a fate that befell the Nazi campaign against jazz music. Its fault

was because it “quintessentially represented the principle of

improvisation, equalling musical freedom,” the music’s

“originators and disseminators…were degenerate blacks

and Jews, and, to a lesser extent and in Europe, libidinous

Gypsies.” The “syncopated rhythm of jazz” was not

conducive to militarism and the easy transmission of propaganda

messages, and finally, jazz was “so individualistic as to be

trivial, compared to the racial-communal, lofty objectives of the

Nazi rulers.”37

The demand for jazz, remarkably, never waned, and radio, long held

by Goebbels to be a revolutionary means of further disseminating his

messages (as when he declared, “We make no bones about it: the

radio belongs to us, to no one else! And we will place the radio at

the service of our idea, and no other idea shall be expressed

through it!”) was, until early 1943, forced to play jazz on

the air for the sake of cheering up the returning frontline

soldiers, for “the needs of the combat troops always came

first.”38

A page from the paper Der

Stuermer. Note the solely

anti-Jewish tone of it. According to Cedric Larson, Goebbels

believed that the “press of Germany should be a piano upon

which the government might play.”

Similarly,

the press, several of which had been important organs and outlets

for Nazi propaganda and promotion during the so-called Kampfzeit

(the “time of struggle,” which is how the Nazis

called the period prior to their power seizure), were

incorporated into the State concept of Gleichshaltung, “which

is, so to say, the foundation-stone of policy of the Third Reich,

and calls for the complete coordination and harmonizing of all

internal and external national activity.”39

Cedric Larson, writing in 1937, reported, “Upon the subject

of press control, Dr. Goebbels declared that he did not see in

censorship either a normal or ideal condition. The press should aid

the government and not criticize in such manner as would shake the

faith of the people in the government. The mission of the press

should be not merely to inform, but also to instruct. The press of

Germany should be a piano upon which the government might play.”40

* * *

Viktor

Reimann, one of Goebbels’ biographers, writes that this attack

on the press, and even on independent thought, came from the fears

of Hitler himself. “He saw in it [the press] essentially a

product of liberalism and the individualist concept –

sufficient reason to despise it from the bottom of his heart. A

press without freedom of opinion was bound to be a caricature. But

freedom of opinion was something Hitler feared and rejected.”41

Goebbels, at this stage, did Hitler’s bidding and swallowed

it up into his Ministry, which then went about creatively and subtly

disseminating the Nazi ethos via these many cultural routes.

Eric

Rentschler concludes his analysis of the German cinema thusly: “If

the Nazis were movie-mad, then the Third Reich was movie-made, a

fantasy order that in equal measure was dream machine and a death

factory.”42

He could easily have been talking about all cultural endeavours and

fields that fell afoul of Goebbels’ obsession with subtlety

and the transmission of Third Reich ideology.

* * * * *

Peter Bjel is a freelance writer and teacher candidate, and holds

degrees in Politics and History from the University of Toronto. He

can be reached at peterbjel@hotmail.com.

This is the second of three articles about Goebbels,

propaganda and the Third Reich.

NOTES:

1

H. R. Trevor-Roper, “Hitler’s Impresario,” New

York Review of Books 25, 9 (1 June 1978), HTML.

2

Viktor Reimann, Goebbels: The Man Who Created Hitler (Garden

City, NY: Doubleday, 1976), p. 166.

3

Ralf Georg Reuth, Goebbels: A Biography (New York: Harcourt

Brace & Company, 1993), p. 192. For the Reich Chamber of

Culture’s formation, see pp. 191-192. Additionally, on the

structure of the Propaganda Ministry and the satellite Chamber of

Culture, see pp. 135-137.

4

Quoted in Roger Manvell and Heinrich Fraenkel, Dr. Goebbels: His

Life and Death (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1960), p.

140.

5

Ibid., p. 141; the point about Lang is my own. This is also the

conclusion of David Stewart Hull, “Forbidden Fruit: The

Harvest of the German Cinema, 1939-1945.” Film Quarterly

14, 4 (Summer 1961): pp. 16-30, at p. 30, who argues that this

problematic legacy carried on into the post-war period.

6

Manvell and Fraenkel, Dr. Goebbels, p. 228.

7

Eric Rentschler, “Ministry of Illusion: German Film,

1933-1945.” Film Comment 30, 6 (November 1994): pp.

34-42, at p. 36.

10

Karsten Witte, “Visual Pleasure Inhibited: Aspects of the

German Revue Film.” New German Critique 24/25 (Autumn

1981/Winter 1982): pp. 238-263, at pp. 238, 243.

12

For a further discussion of Triumph des Willens, see David B.

Hinton, “’Triumph of the Will’: Document or

Artifice?” Cinema Journal 15, 1 (Autumn 1975): pp.

48-57. The opening scene descriptions are from my own observations

and take of the film.

13

Reuth, Goebbels, p. 141.

14

Quoted in Ibid. For a long excerpt from this portion of Der

Angriff, see Jay W. Baird, “From Berlin to Neubabelsberg:

Nazi Film Propaganda and Hitler Youth Quex.” Journal of

Contemporary History 18, 3 (July 1983): pp. 495-515, at p. 500.

15

Baird, “From Berlin to Neubabelsberg,” p. 501.

17

Ibid., p. 495 (for the three points).

18

Quoted in Marcia Klotz, “Epistemological Ambiguity and the

Fascist Text: Jew Suess, Carl Peters, and Ohm Krueger.”

New German Critique 74 (Spring/Summer 1998): pp. 91-124, at

p. 112.

19

Quoted in Ibid., p. 120.

21

As quoted in Klotz, “Epistemological Ambiguity and the Fascist

Text,” p. 119, n. 47. The rest of the descriptions are from

my own observations and take of the film.

22

From my own observations and take of the film.

23

Hull, “Forbidden Fruit,” pp. 19-20, for the story; and

from my own observations and take of the film. On the point about

vampirism, see Klotz, “Epistemological Ambiguity and the

Fascist Text,” pp. 100, 122. The film concludes with the

ominous and cryptic warning: “May the citizens of other states

never forget this lesson.”

24

Klotz, “Epistemological Ambiguity and the Fascist Text,”

p. 97. On Goebbels and these anti-Semitic films, see Reuth,

Goebbels, pp. 261-262, 277-278.

25

Hull, “Forbidden Fruit,” p. 28.

26

Quoted in Reimann, Goebbels, p. 127. The whole episode with

Remarque’s film is described in pp. 126-127; and in William G.

Chrystal, “Nazi Party Election Films, 1927-1938.” Cinema

Journal 15, 1 (Autumn 1975): pp. 29-47, at p. 34.

27

Remarque’s biographer pays much attention to Remarque’s

clashes with the Nazis, and the subsequent banning of his books.

See Hilton Tims, Erich Maria Remarque: The Last Romantic (New

York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003). Tims argues that

post-1945 Germany was painfully (and disgracefully) slow to

reinstate Remarque as part of the country’s literary and

cultural canon. That process is still underway.

28

Wayne Kvam, “The Nazification of Max Reinhardt’s

Deutsches Theater Berlin.” Theatre Journal 40, 3

(October 1988): pp. 357-374, at p. 373.

29

See Alan E. Steinweis, “The Professional, Social, and Economic

Dimensions of Nazi Cultural Policy: The Case of the Reich Theatre

Chamber.” German Studies Review 13, 3 (October 1990):

pp. 441-459, at pp. 444, 447-448.

31

Mary-Margaret Goggin, “’Decent’ vs. ‘Degenerate’

Art: The National Socialist Case.” Art Journal 50, 4

(Winter 1991): pp. 84-92, at p. 86. See p. 89 of her article, on

the fates of the many German artists that had to flee the country

amid the artistic purges.

33

Herbert P. Rothfeder, “’Amt Schrifttumspflege’: A

Study in Literary Control.” German Studies Review 4, 1

(February 1981): pp. 63-78, at p. 65.

35

Quoted in Ibid., p. 72.

36

Ibid., pp. 76-77, for details on this exception. Gerwin Strobl,

“The Bard of Eugenics: Shakespeare and Racial Activism in the

Third Reich.” Journal of Contemporary History 34, 3

(July 1999): pp. 323-336, is a fascinating and shocking piece about

the ways in which Nazi racial ideology was seeped into the German

Shakespeare Society, thereby granting a degree of historical and

artistic legitimacy and prestige to Nazi racial ideas. There can be

no finer example of the corrupting effects Nazi cultural policies

had on all facets of culture in Germany – and beyond.

37

For these four points, see Michael H. Kater, “Forbidden Fruit?

Jazz in the Third Reich.” The American Historical Review

94, 1 (February 1989): pp. 11-43, at p. 13.

38

Ibid., p. 30. The earlier quote by Goebbels on radio is quoted in

Craig, “The True Believer.”

39

Cedric Larson, “The German Press Chamber.” The

Public Opinion Quarterly 1, 4 (October

1937): pp. 53-70, at p. 56.

40

Ibid., p. 57. A fascinating article, based almost exclusively on

the Reich press decree of 4 October 1933 and Nazi Party organs, like

the Voelkischer Beobachter, written on the eve of war.

41

Reimann, Goebbels, p. 206.

42

Rentschler, “Ministry of Illusion,” p. 42.

~~~~~~~

from the November 2011 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|