|

Yiddish Since When?

By Jerry Klinger

May you get passage out of the old village safely, and when you settle, may you fall into the outhouse just as a regiment of Ukrainians is finishing a prune stew and twelve barrels of beer.1

Yiddish Curse

The way it is does not mean the way it was or the way it will be.

- William Rabinowitz

Oy ! 2

When your parent's, your extended family, your neighbors speak Yiddish, and they were all old people to me as a kid, I assumed the world spoke Yiddish; Yiddish, the language of the Yids - the Jew's language. It was the Jewish language from what I thought must have been forever. Of course that did not refer to the Hebrew we learned in the Yeshivah - that was Lashon Ha'Kadosh - the Holy Language, only to be used studying Torah. We were a modern Orthodox Yehshivah. Girls were permitted in our classrooms and studied with us but had to sit on a separate side of the room. In more traditional Yeshivahs, girls are taught separately from boys and not in Hebrew.

Not being much different from many of the kids of my generation, growing up as Americans, trying to assimilate, Yiddish was not on our minds, English and Baseball and girls were.

We really did not want to learn Yiddish. It was the language of the Ghetto, the language of the European Holocaust. If there was a language we wanted to learn, it was the language of freedom, the language they spoke in Israel, the language of the strong independent Jew, Modern Hebrew.

Adults and kids make many assumptions. My assumption did confirm the definition of assume for me. It only made an ass out of you and me. My "assume" about Yiddish was all wrong.

You should lose all your teeth except one, and that one should ache!

Zolst farlirn ale tseyner akhuts eynem, un der zol dir vey ton.

Yiddish is no longer the language spoken by the majority of world Jewry. It is no longer legitimately entitled to the term Yiddish, meaning the language of the Jews. The Holocaust saw to that. Perhaps the language of the Jewish should be..English, Spanish, Polish, Russish, Arabish, Germanish, or God forbid - Hebrew. Even at its height of popularity and usage, Yiddish, though spoken by a significant segment of world Jewry, was never the lingua franca of all Jewry.

So how did Yiddish come to be seen the language of the Jews?

There are two answers, the short answer and the long answer. Hillel, 2000 years ago, was asked by a non-Jew to tell him all about Judaism, while he stood on one foot. He must have been in impatient questioner - probably had to catch a bus or something. Hillel's answer has come to be called the Golden Rule, "Do unto your brothers as you would have them do unto you. The rest is commentary go and learn." Not really sure if Hillel invented that idea. Something similar appears in many different cultures and has pretty much the same meaning among all kinds of folks. Just the same, it still is a darn good lesson.

What can be said about the language of the Jews? There are two answers, the short one and the long one. Even the long one is short. Scholarship of a lifetime of cannot be reduced to a few paragraphs.

First, have I got a short, simple answer, special, just for you? You bet!

Hebrew was the language of the Jews as long as the Jews lived in and controlled their own land. The destruction of the First Temple by the Assyrians (586 BCE), and the beginnings of the Diaspora, brought in a new language, Aramaic. By the third century BCE, Diaspora Jewry having spread west, added Greek to their mother tongues followed shortly by Latin. For the next sixteen hundred years, Hebrew was restricted as mainly a language of religious study and expression. Aramaic was the Yiddish of commonality between widely separated Jewish communities. Jews spoke the language of the lands they resided in.

Jewish language is dynamic if not highly insular. It evolved, adapted and developed into new forms.

Local vernacular was inadequate to express Jewish life. How do you say matzah in Latin or Bulgarian? Hebrew words, Aramaic words, and local language blended over time into new Jewish dialects and even into new languages.

Around the 10th century and on, Jews migrating across Europe, usually at the "encouragement" of local Christian rulers, adopted German as a new foundation for a Hebrew, Aramaic and Slavic mix, a new Jewish language. An Ashkenazic world of a millennium years developed only to be nearly exterminated in the Holocaust. Jews were first welcomed as builders and developers of lands, such as Poland, a thousand years ago. They brought with them the rudiments of what would evolve into many variants of their Jewish-German language -written in Hebrew block letters - Yiddish.

One big problem existed. There were Jews in Poland and there were Jews in Algeria. Algerian Jews, part of the Sephardic world, spoke a Jewish-Arabic language. The Sepharadim and the Ashekenazim each had their own Yiddish. Their Yiddish could not be understood by the other's Yiddish.

In the late 19th century, Jews slowly recognized they needed to have their own land again. To have their own land, they needed to reestablish a universal, unifying, Jewish language. Eliezer Ben Yehuda3 was the very man for the job. He moved to Palestine and devoted his life to give new life to an old language - the birth of Modern Hebrew. Ben Yehuda's vision and the re-establishment of the Jewish state in their own ancient lands, Askenazim and Sepharadim, all Jews everywhere, could communicate in a common Yiddish, once again.

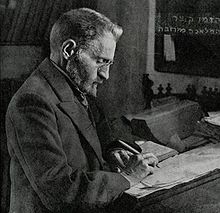

Eliezer Ben Yehuda

Ben Yehuda never envisioned that his dream would create a new problem. Modern Hebrew is not recognized by all Jews as the Jewish language. Where ever Jews live, new Yiddish is still evolving. Have you ever heard of Yidlish?

"That miserable shyster! How dare he finagle his way into Congress!"

Congressional Candidate for office - Mississippi, 2008 election

A short answer is, well, just a short answer.

There is a long answer too, for those who wish to know more, OY!

Prior to 1939, there were almost 80 Jewish languages and dialects4. Jewish languages are rich, and diverse. Jewish languages ranged, for example, from Hebrew-Spanish, to Hebrew-Arabic to Hebrew-Russian, to Hebrew-Malayalam5.

Malayalam was the Jewish language spoken by the Jews formerly of Chochin, India. Most of the Jews of Chochin immigrated to Israel in 1948. The language is gone today but the synagogue of the Chochin Jewish community has been faithfully transported and erected as a museum artifact. It is displayed in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The synagogue of the Chochin community is a curiosity for most Jews, especially Ashkenazim.

Jewish languages are written in many ways and in many forms of local script. Yiddish is written in Hebrew letters, even if the words sounds like garbleized German and should have been written in Latin Text. Jewish languages can be written in transliterated script - Hebrew with Arabic script, or Russian Cyrillic, or Hindu or English or whatever.

"A man comes from the dust and in the dust he will end"-and in the meantime it is good to drink vodka.

"Odem yesode meofe vesofe leofe," beyno-lveyno iz gut a trink bronfn.

So what is a Jewish language? Is it a language spoken only by the Jews? Generally true, but everyone has a story of a goy living amongst the Jews who wanted to do business. In order to do business you have to speak the local language. One famous story is of Hugh McDonald, a Christian volunteer who served on the Aliyah Bet ship the Hatikvah smuggling Jewish Holocaust refugees in to Palestine. He spoke Yiddish better than the American Jewish volunteers who ran the ship. McDonald had worked in a Jewish bakery in Philadelphia. He learned the language first hand. It was he who could communicate with the refugees and help them, not the Jews. McDonald spoke the language.

Bottom line: Jews had to learn to speak, read and write in the local languages wherever the Diaspora took them to survive. Jews are a very insular, separatist, almost isolationist people. We are that way for many reasons - of which simple self protection and self perpetuation are factors. But, if you wanted to buy a cow or sell a nice hand-woven table cloth, you had to be able to communicate with the locals in their language, according to their customs. You did not have to be great but you needed to be understood. Language is fluid and dynamic. Words that were efficient, effective, and had better communication characteristics than Hebrew, were "borrowed" and added to the Jewish language lexicon. Modern Hebrew chooses to "borrow" English words instead of the convoluted Hebrew equivalents for "raadio" - radio, "televizia" - television or "hambourgher" for hamburger, to mention a few. Over the centuries, Jewish languages evolved into their own unique forms. Frequently, Jews speaking their own Yiddish could not communicate with each other.

What are some of the mainline Jewish languages and dialects other than the Yiddish Ashkenazim grew up with? To be honest there are too many to focus on but let's mention a few. The scholarship of the Jewish-Language Org. will assist.

The bigger question, where, when and what did Yiddish come from will have to be continued later in the article.

A rich miser and a fat goat are of no use until they are dead!

Fyn a kargn gvir in fet bok genist men ersht nukhn toyt

Jewish Aramaic and Neo-Aramaic

"The Aramaic language has been around for over three thousand years, beginning in the 11th century B.C.E as the official language of the first Aramean states in Syria. A few centuries later it became the official language, or lingua franca, of the Assyrian and Persian empires, covering vast areas, and gradually splitting into two major (groups of) dialects, Eastern and Western.

The first attested Jewish Aramaic texts are from the Jewish military outpost in Elephantine, ca. 530 B.C.E. Other Jewish Aramaic texts are the Books of Ezra (ca. 4th cent. B.C.E.) and Daniel (165 B.C.E.). Starting around 250 C.E., Bible translations such as the Targums of Onkelos and Jonathan began to appear. The division into Eastern and Western Aramaic is most evident in the Palestinian (Yerushalmi) Talmud (Western, completed ca. 5th century C.E.; and Midrashim, ca. 5th-7th centuries C.E.) and the Babylonian Talmud (Eastern, finished ca. 8th century C.E.).

With the Islamic conquests, Aramaic was quickly superseded by Arabic. Except for some occasional bursts such as the Book of Zohar and other kabbalistic literature (ca. the 12th cent), it almost ceased as a literary language, but remained as ritual and study language. It continued its life as a spoken language until our days by the Jews and Christians of Kurdistan and three villages (mostly Christians and some Muslims) in Syria. Syriac-Aramaic is still used as a ritual language among many Near Eastern Christians.

The oldest literature in Jewish (and Christian) Neo-Aramaic is from ca. 1600 C.E. It includes mostly adaptations or translations of Jewish literature, such as Midrashim (homiletic literature), commentaries on the Bible, hymns (piyyutim), etc. Jewish Neo-Aramaic may be divided into 3-4 major groups of dialects, some mutually intelligible, and others not or hardly so. Also, in a few towns both Jews and Christians spoke Neo-Aramaic, but using distinct dialects. The Neo-Aramaic-speaking Jews immigrated to Israel in the early 1950s, and their language was superseded by Hebrew.

Aramaic is a close sister of Hebrew and is identified as a "Jewish" language, since it is the language of major Jewish texts (the Talmuds, Zohar, and many ritual recitations, such as the kaddish). Aramaic has been until our present time a language of Talmudic debate in many traditional Yeshivot, as many rabbinic texts are written in a mixture of Hebrew and Aramaic. Jewish Neo-Aramaic is both an "extension" of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic .and a Neo-Jewish language. The Jewish Neo-Aramaic texts are written in a Hebrew alphabet, like most Jewish languages, but the spelling is phonetic.. As in other Jewish languages, many Judaic and even some secular terms are borrowed from Hebrew, rather than being inherited from traditional Jewish Aramaic... Hebrew loanwords were one of the major features that distinguished Jewish Neo-Aramaic dialects from their Christian counterparts.. Yet what may be a typical grammatical or lexical feature of a Jewish dialect in one place may be known elsewhere as a Christian feature." 6

A righteous man who knows he is righteous is not righteous.

A tsadik vos vais az er iz a tsadik iz kain tsadik nit

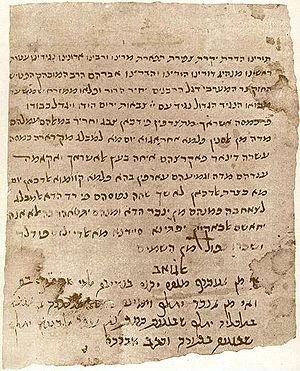

Page from the Cairo Geniza Cairo, part of which is written in the Judeo-Arabic language

"Judeo-Arabic languages are a collection of Arabic language dialects spoken by Jews living or formerly living in Arabic-speaking countries. Just as with the rest of the Arab world, Arabic-speaking Jews had different dialects representative of the different regions in which they lived. Most Judaeo-Arabic dialects were written in modified forms of the Hebrew alphabet, often including consonant dots from the Arabic alphabet to accommodate phonemes that did not exist in the Hebrew alphabet.

In retaliation for 1948 Arab-Israel War, Jews in Arab countries became subject to increasingly insufferable discrimination and violence. Pogroms occurred in many Arab countries. Virtually all of the Jews from Arab lands fled mainly to Israel. Their dialects of Arabic did not thrive in Israel, and most became extinct, replaced by the Modern Hebrew language.

In the Middle Ages, Jews in the Islamic Diaspora spoke a dialect of Arabic, which they wrote in a mildly adapted Hebrew script (rather than using Arabic scrip).

Some of the most important books of medieval Jewish though were originally written in Judeo-Arabic, as well as certain halakhic works and biblical commentary. Only later were they translated into medieval scientific Hebrew so that they could be read by the Askenazic Jews of Europe. These include:

Saadia Gaon's Emunot ve-Deot, his Tafsir (biblical commentary and translation), and his siddur (the explanatory parts, not the prayers themselves)

Solomon ibn Gabirol's Tikkun Middot ha-Nefesh

Bahya ibn Pakuda's Hovot ha-Levavot

Judah Halevi's Kuzari

Maimonides' Commentary on the Mishnah, Sefer ha-Mitzvot, Guide to the Perplexed, and many of his letters and shorter essays."7

"Judeo-Arabic is an ethnolect (a linguistic entity with its own history and used by a distinct language community) which has been spoken and written in various forms by Jews throughout the Arabic-speaking world.

Judeo-Arabic can be divided into five periods: Pre-Islamic Judeo-Arabic (pre-eighth century), Early Judeo-Arabic (eighth/ninth to tenth centuries), Classical Judeo-Arabic (tenth to fifteenth centuries), Later Judeo-Arabic (fifteenth to nineteenth centuries), and Modern Judeo-Arabic (twentieth century). Much of what we know about Classical Judeo-Arabic comes from documents found in the Cairo Geniza.

It is almost impossible to determine a precise date for the origin of Judeo-Arabic. There is some evidence that the Jews in the Arabian Peninsula used some sort of Arabic Jewish dialect even before the Islamic conquests (600s C.E.). Referred to as al-Yahudiyya, this dialect was similar to the dominant Arabic dialect but included some Hebrew and Aramaic vocabulary, especially in the religious and cultural domains. Some of these loan words passed into the speech and writings of the Arabs, thus accounting for the Hebrew and Aramaic origins of certain Koranic words. There is no evidence that Pre-Islamic Judeo-Arabic produced any literature, especially if we examine the language of the Jewish poet as-Samaw'al bnu 'Adiya', which did not differ from that of his Arab contemporaries. His poetry is part of the canon of Arabic literature - not Jewish literature. In fact, if Arab sources had not reported that he was Jewish, we never would have known. On the other hand, there may have been some al-Yahudiyya writings in Hebrew characters in the pre-Islamic period.

After the great conquests of early Islam, the Jews in the newly conquered lands adopted the language of the conquerors and began to incorporate Arabic into their writings, slowly developing, at times, their own spoken dialect. In the following centuries, Jewish varieties of Arabic came to exist all around the Arabic-speaking world, from Iraq and Yemen in the East to Spain and Morocco in the West.

In the late fifteenth century, Judeo-Arabic underwent a dramatic change, as many Jews, especially in North Africa, began to associate less with Arabs and the Arabic language and culture (this was less the case in Yemen, where strong contact persisted for some time afterward.. This cultural development was reflected both in the linguistic structure and in the literature. Written Judeo-Arabic at that time incorporated more dialectal elements, and more and more works appeared in Hebrew..

Like other Jewish languages, Judeo-Arabic has a base language..Arabic.and a large Hebrew and Aramaic component..

Like most other Jewish languages, written Judeo-Arabic consistently uses Hebrew characters. Very frequently Jews adopted the spelling conventions of Talmudic orthography, employing the final forms of Hebrew letters and sometimes adapting existing consonants and/or symbols as vowel signs. Thus, the Hebrew script symbolizes the Jewish nature of the ethnolect community. It is not uncommon to use script as a religious identification for a language.

Judeo-Arabic uses various traditions of orthography to transmit different political, cultural, and religious messages, as can be seen in other Jewish languages. For example, Late Judeo-Arabic is written in a Hebraized orthography, helping to convey Jewish identity.

Jewish speakers have usually considered their varieties to be separate from the local languages, giving them special names such as illu?a dyalna 'our language.' In Morocco, Jews call Moroccan Judeo-Arabic il'arabiyya dyalna 'our Arabic' and general Moroccan Arabic il'arabiyya dilmsilmin'Arabic of the Muslims.'

Indeed, spoken Judeo-Arabic is sometimes unintelligible to people outside the community (it is obvious that Jewish languages written in Hebrew script are unintelligible to most non-Jews)..

Judeo-Arabic has been written by Jews for Jewish readership usually on Jewish topics. However, there have also been translations of non-Jewish literature into Judeo-Arabic, often incorporating Jewish imagery. This can also be seen, for example, in Yiddish and Judeo-Spanish.

Jewish ethnolects around the world share an important literary genre: the verbatim translation of sacred and liturgical Hebrew/Aramaic texts (sar? in Judeo-Arabic, tayts in Yiddish, ladino in Judeo-Spanish, sar' in Jewish Neo-Aramaic, for example). The translations included the Bible, the Siddur(prayer book), the Passover Haggadah, Pirke Avot (Ethics of the Fathers), and more. The sar?tradition involves word-for-word translation into the Arabic lexicon, maintaining the syntax of the original Hebrew/Aramaic text."8

Twice a year the poor are badly off: summer and winter.

Tsvai mol a yor iz shlecht dem oreman: zumer un vinter.

Judeo-Persian:

"More than five hundred years after the end of the Achaemenid Empire (550-330 BCE), the Jews of the Babylonian Diaspora again came under the dominion of the Persians. For Persian Jews the Persian language held a position similar to that held by the Greek language among the Jews of the West. Persian became to a great extent the language of everyday life among the Jews of Babylonia. A hundred years after the conquest of that country by the Sassanids an amora of Pumbedita, Rab Joseph (d. 323), declared that the Babylonian Jews had no right to speak Aramaic, and should instead use either Hebrew or Persian."9

"Judeo-Persian is the common name for both the literary and spoken forms of Jewish Iranian language varieties. In addition to Judeo-Persian from Persia/Iran, it frequently includes Judeo-Tadjik / Tajik / Tadzhik (otherwise known as Bukharan, Judeo-Bukharan, Bukhari, Bukharit) and sometimes also Judeo-Tat (Cuhuri / Juhuri / Dzhuhuri, the language of the Mountain Jews in Dagestan and Northern Azerbayjan.

There has never been a variety of spoken Judeo-Persian common to all Persian Jews. The Jews spoke their local dialect, with some "Jewish" traits, just as their Muslim, Christian, or Zoroastrian neighbors spoke basically the same dialect, with their own communal, professional, or caste-based traits. These dialects varied from area to area. In some cases, they were dialects of Persian, but in other cases they were non-Persian Iranian (or other) dialects. In the pre-Mongol period such non-Persian dialects were sometimes used for writing, as is indicated by a literary document found in the Cairo Geniza. During the same period dialects of Persian were also written, as is indicated by the Tafsir of Ezekiel..

.Like many other Jewish languages, the earliest examples we have of New Persian are written in Jewish characters.

For centuries, literary Judeo-Persian co-existed alongside vernaculars, exactly as was - and to some degree, still is - the case with Common (i.e., Muslim) New Persian. ..As we can see, although written Judeo-Persian served as the main tool of literary expression, it was merely one of the linguistic layers used by Iranian Jewry..

Judeo-Persian texts can be divided into two periods: before the Mongol invasion in the mid-13th century and afterwards. Like in the Common Persian literary tradition, the Mongol onslaught was a period of serious cultural and linguistic change. Judeo-Persian texts dating from before the Mongol invasion exhibit considerable dialect variety; in the post-Mongol period all this changed.. For writing the Jews used the same language as their Muslim compatriots, with minor differences.. The spelling was sometimes phonetic, due to the lack of Muslim education..

The literature before the Mongol invasion comes mainly from geniza finds made in the 19th century and during archeological excavations. In the 14th-17th centuries Judeo-Persian literature flourished. In Bukhara the peak was in the 17th-19th centuries, with renewed activity in Jerusalem in the late 19th - early 20th century.

As a Jewish language, written Judeo-Persian belongs to the same type as written Judeo-Arabic of the Classical period...is written in Hebrew characters, and includes some Hebrew loanwords (but not as many as in Yiddish). The presence of Aramaic loanwords is significant, probably going back to the earliest stages of Judeo-Persian.. One of the most interesting facts about Judeo-Persian literature is that it includes many Muslim-Persian literary works, especially poetry, transcribed into Hebrew characters. Original Judeo-Persian poetry, especially rewriting of Biblical books and Mishnaic tractates, is another distinctive mark of medieval Judeo-Persian literary production.

Literary Judeo-Persian is now extinct; some literary activities are carried on in Israel in Judeo-Bukharan and, to a much lesser extent, in Judeo-Tat; Iranian Jews in Israel and the USA use standard New Persian (as well as Hebrew and English) for their literary production.

However, spoken varieties of Persian and other Iranian languages are still common among Jews."10

All the problems I have in my heart, should go to his head.

Ale tsores vos ikh hob oyf mayn hartsn, zoln oysgeyn tsu zayn kop

Ladino11

"Ladino, otherwise known as Judeo-Spanish, is the spoken and written Hispanic language of Jews of Spanish origin. Ladino did not become a specifically Jewish language until after the expulsion from Spain in 1492 - it was merely the language of their province. It is also known as Judezmo, Dzhudezmo, or Spaniolit.

When the Jews were expelled from Spain and Portugal they were cut off from the further development of the language, but they continued to speak it in the communities and countries to which they emigrated. Ladino therefore reflects the grammar and vocabulary of 14th and 15th century Spanish. The further away from Spain the emigrants went, the more cut off they were from developments in the language, and the more Ladino began to diverge from mainstream Castilian Spanish.

In Amsterdam, England and Italy, those Jews who continued to speak 'Ladino' were in constant contact with Spain and therefore they basically continued to speak the Castilian Spanish of the time. However, in the Sephardi communities of the Ottoman Empire, the language not only retained the older forms of Spanish, but borrowed so many words from Hebrew, Arabic, Greek, Turkish, and even French, that it became more and more distorted. Ladino was nowhere near as diverse as the various forms of Yiddish, but there were still two different dialects, which corresponded to the different origins of the speakers.

'Oriental' Ladino was spoken in Turkey and Rhodes and reflected Castilian Spanish, whereas 'Western' Ladino was spoken in Greece, Macedonia, Bosnia, Serbia and Romania, and preserved the characteristics of northern Spanish and Portuguese. The vocabulary of Ladino includes hundreds of archaic Spanish words which have disappeared from modern day Spanish, and also includes many words from different languages that have been substituted for the original Spanish word, from the various places Ladino speaking Jews settled.

Some terms were actually transferred from one community to another through commercial or cultural relations, whereas others remained peculiar to particular communities. These foreign words derive mainly from Hebrew, Arabic, Turkish, Greek, French, and to a lesser extent from Portuguese and Italian. In the Ladino spoken in Israel, several words have been borrowed from Yiddish. For most of its lifetime, Ladino was written in the Hebrew alphabet, in Rashi script, or in Solitro, a cursive method of writing letters. It was only in the 20th century that Ladino was ever written using the Latin alphabet. In fact, what is known as 'Rashi script' was originally a Ladino script which became used centuries after Rashi's death in printed books to differentiate Rashi's commentary from the text of the Torah.

At various times Ladino has been spoken in North Africa, Egypt, Greece, Turkey, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania, France, Israel, and, to a lesser extent, in the United States (the highest populations being in Seattle, Los Angeles, New York, and south Florida) and Latin America. By the beginning of this century, with the spread of compulsory education in the language of the land, Ladino began to disintegrate. Emigration to Israel from the Balkans hastened the decline of Ladino in Eastern Europe and Turkey.

The Nazis destroyed most of the communities in Europe where Ladino had been the first language among Jews. Ladino speakers who survived the Holocaust and immigrated to Latin America tended to pick up regular Spanish very quickly, whilst others adopted the language of whichever country they ended up in. Israel is now the country with the greatest number of Ladino speakers, with about 200,000 people who still speak or understand the language, but even they only know a very limited and basic Ladino."12,13

Man rides, but God holds the reins.

Der mentsh fort un Got halt di laitses

To every answer you can find a new question.

Oif itlechen terets ken men gefinen a nei'eh kasheh

Yiddish, the Mamma Loshen,

How should that be translated? How can Mamma Loshen be translated- the language of our mother, the mother language of the Jews?

Historically, most of the Yiddish speakers were of Ashkenazic European background. They were secular, and or religious Jews. Today, Yiddish speakers are heavily concentrated amongst the Haredim, the very religious communities in Israel, the U.S. and Great Britain. Even within this subgroup of Jewish life, Yiddish is not the universal language spoken or understood fluently. There are a few smatterings of Yiddish speakers elsewhere in academia and those into cultural nostalgia. Yiddish as "the" language of secular Ashkenazic Jewry is virtually no more.

Hebrew, English or Russian are the languages of choice spoken by most Jews.

Where did Yiddish come from? How did it develop and why is it called the Mamma Loshen? Is Yiddish a language or a culture? Why is the term Yiddishkeit so commonly understood, and misunderstood, in the Jewish world? We don't say Jewishkeit, or Israelikeit?14

Jewish identity is a fork in the road that any traveler gets lost taking. What is a Jew? Who is a Jew? What if a Jew does not want to be a Jew, are they still a Jews?

Jews have fought. They are still fighting amongst themselves over far less than trying to understand what they are.

Returning to the first question, Yiddish? Where did it come from, when and how?

Yiddish

"The language originated in the Ashkenazi culture that developed from about the 10th century in the Rhineland spreading to Central and Eastern Europe. In the earliest surviving references to it, the language is called ???????????? (loshn-ashknez = "language of Ashkenaz") and ????? (taytsh, a variant of tiutsch, the contemporary name for the language otherwise spoken in the region of origin, now called (Middle High German). In common usage, the language is called ?????????? (mame-loshn, literally "mother tongue"), distinguishing it from Biblical Hebrew and Aramaic, which are collectively termed ????????? (loshn-koydesh, "holy tongue"). The term "Yiddish" did not become the most frequently used designation in the literature of the language until the 18th century.

For a significant portion of its history, Yiddish was the primary spoken language of the Ashkenazi Jews spanning a broad dialect continuum from Western Yiddish to three major groups within Eastern Yiddish, namely Litvish, Poylish and Ukrainish. Eastern and Western Yiddish are most markedly distinguished by the extensive inclusion of words of Slavic origin in the Eastern dialects. While Western Yiddish has few remaining speakers, Eastern dialects remain in use.

Nothing is known about the vernacular of the earliest Jews in Germany, but several theories have been put forward. It is generally accepted that it was likely to have contained elements from other languages of the Near East and Europe, absorbed through dispersion. Since many settlers came via France and Italy, it is also likely that the Romance-based Jewish languages of those regions were represented.

Members of the 10th century Ashkenazi community would have encountered the myriad dialects from which standard German was destined to emerge many centuries later. They would soon have been speaking their own versions of these German dialects, mixed with linguistic elements that they themselves brought into the region. These dialects would have adapted to the needs of the burgeoning Ashkenazi culture and may, as characterizes many such developments, have included the deliberate cultivation of linguistic differences to assert cultural autonomy. The Ashkenazi community also had its own geography, with a pattern of relationships among settlements that was somewhat independent of its non-Jewish neighbors. This led to the consolidation of Yiddish dialects, the borders of which did not coincide with the borders of German dialects.

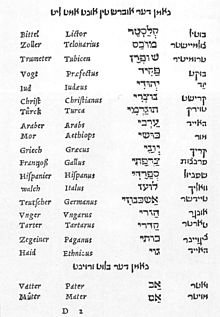

A page from the Shemot Devarim (literally Names of Things), a Yiddish-Hebrew-Latin-German dictionary and thesaurus, published by Elia Levita in 1542

Apart from the obvious use of Hebrew words for specifically Jewish artifacts, it is very difficult to determine the extent to which the Yiddish spoken in any earlier period differed from the contemporary German. There is a rough consensus that by the 15th century Yiddish would have sounded distinctive to the average German ear, even when restricted to the Germanic component of its vocabulary.

The oldest surviving literary document in Yiddish is a blessing in the 1272 Worms

gut tak im betage se vaer dis makhazor in beis hakneses trage

May a good day come to him who carries this prayer book into the synagogue.

Over the course of the 14th and 15th centuries, songs and poems in Yiddish, and also macaronic pieces in Hebrew and German, began to appear. These were collected in the late 15th century by Menahem ben Naphtali Oldendorf. During the same period, a tradition seems to have emerged of the Jewish community's adapting its own versions of German secular literature. The earliest Yiddish epic poem of this sort is the Dukus Horant, which survives in the famous Cambridge Codex T.-S.10.K.22. This 14th-century manuscript was discovered in the geniza of a Cairo synagogue in 1896, and also contains a collection of narrative poems on themes from The Hebrew Bible and the Haggadah.

The development of the printing press resulted in an increase in the amount of material produced and surviving from the 16th century and onwards. One particularly popular work was Elia Levita's Bovo-Bukh, composed around 1507-08 and printed in at least forty editions, beginning in 1541. Levita, the earliest named Yiddish author, may also have written Paris and Vienna. Another Yiddish retelling of a chivalric romance, Vidvilt (often referred to as "Widuwilt" by Germanizing scholars), presumably also dates from the 15th century, although the manuscripts are from the 16th. It is also known as Kinig Artus Hof, an adaptation of the Middle High German romance Wigalois by Wirnt von Gravenberg. Another significant writer is Avroham ben Schemuel Pikartei, who published a paraphrase on the Book of Job Book in 1557.

Women in the Ashkenazi community were traditionally not literate in Hebrew, but did read and write Yiddish. A body of literature therefore developed for which women were a primary audience. This included secular works, such as the Bovo-Bukh, and religious writing specifically for women, such as the Tseno Ureno and the Tkhines. One of the best-known early woman authors was Gluckel of Hameln, whose memoirs are still in print.

The Western Yiddish dialect - sometimes pejoratively labeled Mauscheldeutsch (from Moischele-Deutsch or "Moses German") - began to decline in the 18th century, as the Enlightenment and the Haskalah led to the view of Yiddish as a corrupt dialect. Assimilation and the incipient creation of Modern Hebrew were significant factors in the decline.

In Eastern Europe, the response to assimilation took the opposite direction. Yiddish became a cohesive force in a secular Jewish culture.

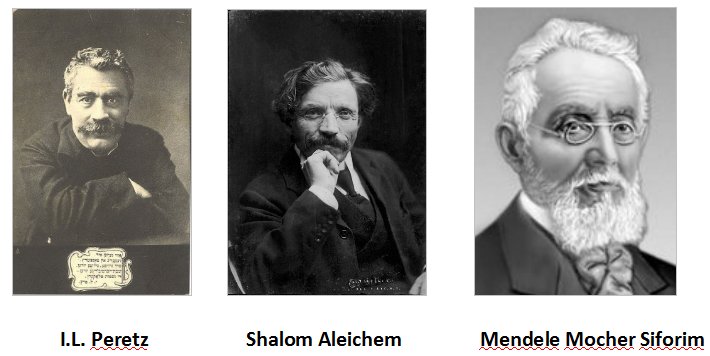

Many consider late 19th and early 20th century the Golden Age of secular Yiddish literature. It coincided with the development of Modern Hebrew as a spoken and literary language, from which some words were also absorbed into Yiddish. Three 19th century popular culture Yiddish authors are considered the popularizers of the modern Yiddish literary genre. The first was Sholem Yankev Abramovitch, writing as Mendele Mocher Sforim. The second was Sholem Rabinovitsh, widely known as Sholem Aleichem, whose stories about ????? ??? ???????? (tevye der milkhiker = Tevye the Dairyman) inspired the Broadway musical and film Fiddler on the Roof. The third was Isaac Leib Peretz.

In the early 20th century, especially after Socialist October Revolution in Russia, Yiddish was emerging as a major Eastern European language. Its rich literature was more widely published than ever, Yiddish, Yiddish theatre and Yiddish film were booming, and it even achieved status as one of the official languages in Belorussia, Sweden and the short-lived Galician SSR. Educational autonomy for Jews in several countries (notably Poland) after World War I led to an increase in formal Yiddish-language education, more uniform orthography, and to the 1925 founding of the Yiddish Scientific Institute, YIVO15 . "

"Founded in 1925 in Vilna, Poland (Wilno, Poland, now Vilnius, Lithuania), as the Yiddish Scientific Institute, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research is dedicated to the history and culture of Ashkenazi Jewry and to its influence in the Americas. Headquartered in New York City since 1940, today YIVO is the world's preeminent resource center for East European Jewish Studies; Yiddish language, literature and folklore; and the American Jewish immigrant experience. The YIVO Library holds over 385,000 volumes in 12 major languages, and the Archives contains more than 24,000,000 pieces, including manuscripts, documents, photographs, sound recordings, art works, films, posters, sheet music, and other artifacts. YIVO also offers a series of cultural events and films, adult education and Yiddish language classes (including the pioneering Uriel Weinreich Program in Yiddish Language, Literature and Culture six-week intensive summer program begun in 1968), various scholarly publications, research opportunities and fellowships."16

"Yiddish emerged as the national language of a large Jewish community in Eastern Europe that rejected Zionism and sought Jewish cultural autonomy in Europe. It also contended with Modern Hebrew as a literary language among Zionists.

On the eve of World War II, there were 11 to 13 million Yiddish speakers. The Holocaust, however, led to a dramatic, sudden decline in the use of Yiddish, as the extensive Jewish communities, both secular and religious, that used Yiddish in their day-to-day life were largely destroyed. Around 85 percent of the Jews that died in the Holocaust - five million people - were speakers of Yiddish. Although millions of Yiddish speakers survived the war (including nearly all Yiddish speakers in the Americas), further assimilation in countries United States and the Soviet Union, along with the strictly monolingual stance of the Zionist movement, led to a decline in the use of Eastern Yiddish.

Opposing views exist among secular Jews worldwide, one side seeing Hebrew (and Zionism) and the other Yiddish (and Internationalism) as the means of defining emerging Jewish nationalism. The opposing views have severely exacerbated conflicts between Jews and their identity.

In the 1920s and 1930s, gdud meginéy hasafá, "the language defendants regiment", whose motto was ivrí, dabér ivrít "Hebrew [i.e. Jew], speak Hebrew!" used to tear down signs written in "foreign" languages and disturb Yiddish theatre gatherings. However, according to linguist Ghil'ad Zuckermann, the members of this group in particular, and the Hebrew revival in general, did not succeed in uprooting Yiddish patterns (as well as the patterns of other European languages Jewish immigrants spoke) within what he calls "Israeli", i.e. Modern Hebrew. Zuckermann believes that "Israeli does include numerous Hebrew elements resulting from a conscious revival but also numerous pervasive linguistic features deriving from a subconscious survival of the revivalists' mother tongues, e.g. Yiddish." 17

"There is a growing revival of interest in Yiddish culture among secular Israelis, with the flourishing of new proactive cultural organizations like YUNG YiDiSH, as well as Yiddish theater (usually with simultaneous translation to Hebrew and Russian) and young people are taking university courses in Yiddish, some achieving considerable fluency."18

To learn the whole Talmud is a great accomplishment; to learn one good virtue is even greater.

Durchlernen gants shas iz a groisseh zach: durch lernen ain mideh iz a gressereh zach.

The first Jewish immigrants to the Americas and the United States were of Sephardic origins. They did not speak Yiddish. The second wave of Jewish immigration to the United States (1820-1860) were German, non Yiddish, speaking Jews. It was not until the mid to late 19th century, with the massive arrival of Eastern European Jews, that Yiddish became dominant within the immigrant community. Yiddish language commonality helped to bond Jews together in the United States as they transitioned and eventually assimilated into American culture.

Yiddish newspapers, such as the Forward19(Forverts - Yiddish) edited by Abraham Cahan20, served as forums for Jews of different European backgrounds. The Forward was one of seven Yiddish daily newspapers in New York City alone. The Yiddish Forward is published weekly. It is available in an online edition. The Forward is published in English. Its Yiddish audience and market is largely gone. Surviving Yiddish newspapers are limited market papers aimed at the Haredi communities such as the Lubavitch21 and Satmar22 communities.

Yiddish life, for that matter European Jewish life, has been a contradiction in America. Jewish immigrants came to the "Goldene Medina23" with their Yiddish and Old World identity. It was quickly shed. It was replaced by a new, desired and still undefined American Jewish identity.

Abraham Cahan, besides being the editor of the Jewish Daily Forward, was also a prolific story writer revealing the Jewish immigrant world of the Lower East Side of New York. One of his most famous stories was Yekl24. Yekl was about a Jewish man, Jacob who came over to America seeking opportunity for himself and his family back in Europe. He quickly found it by rejecting his Old World ways. When he finally brought his wife and son over from Europe he was horrified at the "Greene", their Old Jewish ways, language, customs, even their dress. He was repulsed by them. He divorced Yekl for a flashy, assimilated Jewess. Within a few years, Yekl had also assimilated. She became American in every way. She even lost the proverbial head scarf she wore when she arrived, so denigratingly referred to, even today, as a schmatta. Jacob yearned for her again. But, he was married to his new shrewish American assimilated Jewish wife. He could not go back to what he had lost.

Large scale Eastern European Jewish immigration to the United States ended in the early 1920's. The fresh infusion of Yiddish culture25 and Yiddish speaking Jews ended. In the course of time the generations passed. The promise of America remained if one was one willing to become American and reject being European. Many of the children, most of the grandchildren and almost all of the great-grandchildren of the huge Eastern European/Russian Jewish immigrations left Yiddish as their primary language.

From 1929-1956, a popular radio and television program in the United States was The Goldbergs26. Written and starred in by Gertrude Berg. Ostensibly, the program was about life in the Jewish/Yiddish immigrant ghetto of the Bronx and later the suburbs. It was very successful because it was not too Jewish. It was human and it was American addressing the common concerns of a still blending, universal American immigrant culture. For most Americans, it was the first introduction to American Jewish life, complete with Yiddish European accents, expressions, terms, grammar and inverted sentence structure.

"In 1976, the Canadian-born American author Saul Bellow received the Nobel Prize in literature. He was fluent in Yiddish, and translated several Yiddish poems and stories into English, including Isaac Bashevis Singer's "Gimpel the Fool".

In 1978, the Polish-born Yiddish author Isaac Bashevis Singer, a resident of the United States, received the Nobel Prize in Literature."27

In recent years, academia and small Yiddish centered secular ethnic groups has revitalized moribund interests in the very rich Yiddish past. A small revitalization of Yiddish theatre and the much larger energetic interest in the exciting sounds of Klezmer Yiddish music keep Yiddish alive in America.

Today, Yiddish, for most American Jews, is purely a cultural artifact. A few Yiddish words are sprinkled here and there, some having leached into the general non-Jewish American culture. American "Jewish" delicatessens serve the ever popular specialty, the Reuben Sandwich. The Reuben Sandwich recipe is a kosher style meat -your choice of pastrami, corned beef, etc. - with Swiss cheese, sour kraut, dressing on the side to save calories and piled between two slices of the Yiddish world's favorite bread, Jewish rye. For color, a half done, heavily salted pickle, like grandma used to get from the pickle lady who stood outside on the street corner over her pickle barrels, in rain, snow and heat, on Hester Street, working to put her son through medical school, is the mandatory garnish. The delicacy is ubiquitously offered to eager Jewish and non-Jewish patrons alike. It is a heart attack in waiting.

So how did Yiddish come to be seen as the language of the Jews? The simple answer will irritate many - shear Askenazic arrogance, ignorance, narcissism. The definition is driven by the force of numbers and the fogginess of history.

The Yiddish language is a part of the wonderful, long and rich tapestry of who is and what is a Jew? It is a part of Jewish life but it is not Jewish life by itself. It is not what makes a Jew a Jew.

Jewish life, Jewish language, is adaptive, evolving and wonderfully, always changing. There's a whole new world out there waiting to be discovered.

So, let's enjoy!

What will be the "Yiddish" of the future - God only knows.

May you be a hard-working Jewish writer, and may you be studious, conscientious, and passionate in your work, and may you have wonderful readers who appreciate your humor, your research, and your dedication - and may every ethnic humor book publisher say, "too Jewish!"

Jerry Klinger is president of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation

http://www.jewish-american-society-for-historic-preservation.org

Jashp1@msn.com

1http://www.aish.com/j/fs/Yiddish_Curses_for_the_New_Millennium.html

2The Wife's opinion

3 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eliezer_Ben-Yehuda

4 27 Jewish languages and or dialects are extinct or near extinct

5 http://www.jewish-languages.org/jewish-malayalam.html

6 http://www.jewish-languages.org/jewish-aramaic.html

7 http://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judeo-Arabic languages

8 http://www.jewish-languages.org/judeo-arabic.html

9 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jud%C3%A6o-Persian

10 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jud%C3%A6o-Persian

11http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1tLwuFFMIgg&feature=related

12http://www.sephardicstudies.org/quickladino.html

13http://www.sephardicstudies.org/ladino/ladino-sample.mp3

14 Comment from a non-Jewish friend who read the article. "And I add not only in the Jewish world. I often heard non tribal folk speak of Yiddish saying it is what we dummies call pig Latin..at least in the Wild West where I once called home. Yup, they did and that is what they thought Yiddish was. Interesting or amazing???? I could never figure out that elusive pig Latin thing anyway. My brother called me stupid!"

15http://www.yivoinstitute.org/

16http://www.yivoinstitute.org/

17http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yiddish language

18http://www.jewish-languages.org/yiddish.html

19http://www.forward.com/

20http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraham Cahan

21http://lubavitch.com

22http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Satmar (Hasidic dynasty)

23 The Golden Country - a Yiddish description of America

24http://www.ibiblio.org/eldritch/cahan/yekl.htm

25http://www.laits.utexas.edu/gottesman/

26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The Goldbergs

27http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yiddish language

~~~~~~~

from the January 2012 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

Material and Opinions in all Jewish Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish Magazine accepts no liability for material used.

|