|

|

November 2004 |

|

Search our » History » Holidays » Humor » Places » Thought » Opinion & Society » Writings » Customs » Misc.

|

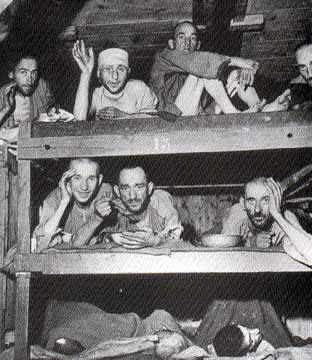

The Walking Corpses of Madjanek: a Birthright Tradition by David Young

I waited for my eyes to adjust in the darkness. I walked slowly down the freezing hall, toward the cages, toward It. A distinct part of me wanted to savor this moment. Shoes with no feet, locked in chicken-wire prisons. Some were made of wood, like the shoes of large puppets. I looked for cloth shoes. I found them. They were green. I touched them. But my gloves, I shed them as quickly as I could—I had to feel their textures, their stories — I had to know them — so I jammed my fingers through the cage wiring, drooling for a taste—then my fingertips grazed them. And suddenly, there was nothing, only silence. I wasn’t breathing. The barracks were filled with hundreds of thousands of shoes belonging to dead Jews, and when I touched them I felt nothing. No flashbacks, no collective unconscious, no swollen throat, not even a tear. All I really wanted was a tear—maybe some indication that I was alive. But there was only my breath warming the icy shoes in front of me. It wasn’t enough. It would never be enough. Then I was abruptly enveloped in a cloud of fury, and I had no idea why.

On a Birthright Israel trip this past December I visited a number of concentration camps in Poland, the first of which was Madjanek. When we returned to the hotel after visiting the freezing camp, the whole group was exhausted but still fuming with rage. After carefully pulling aside a close friend, Svetlana, I told her that my anger felt somehow contrived, that I was not as depressed as I thought I should be and definitely not as angry as everyone else seemed. I confided that I felt furious but honestly couldn’t say why, so I was worried that it meant I was a bad Jew if I didn’t feel personally invested in the atrocities of the Holocaust. Upon hearing my confession, Svetlana remained silent as her eyes swelled with tears and her lips began to tremble. She felt the same way I did, she soon told me, and she was equally terrified of what it might mean. We spent the rest of the night together like two hell-bound miscreants desperately trying to understand the precise moment we decided to sell our souls and snuff out our own salvation. Yet embedded in our self-scrutiny was some undeniable voice shouting that ‘normal’ Jews lost all composure at the camps. But this voice had not simply begun on this trip; it began long ago when we were children, members of the greatest story-telling audience. As adult visitors to Poland, however, we forced ourselves to feel sad and angry to honor the storytellers of our youth, our survivor grandparents. So there we were, Svetlana and I, depressed in a Polish hotel, fighting a fight that our ancestors had already won, for the end of the Holocaust was a great victory that somehow got the best of every Jew on the planet. As if we hadn’t already sensed this, we returned to Europe to resist a long-gone Reich simply because—on some level—fighting makes people feel alive. And it certainly did at these camps both now and then. In October 1942, after many women smuggled gunpowder piecemeal into Birkeneau by hiding it in their vaginas, a group of Jews obliterated a gas chamber and crematorium. When we saw the remnants of this building in person, I tried to imagine the incredible sense of purpose that those men and women experienced that year and especially on that day. Svetlana and I wanted to experience what our grandparents endured and triumphed over; we wanted to sample the sweet taste of freedom fighting, but we never anticipated the possibility that we would feel nothing. So until we flushed out our feelings, we had been brewing in a cauldron of contrived rage that was pointing the wrong way. We slowly came to realize that we were emptying angry rhetoric on dead Nazis as a ploy to deny the fact that we were not lost in a sea of torturous agony at the camps. After considering the possibility that only Svetlana and I felt this way, I privately asked many others on the trip how they felt walking through the camp, and most of them felt just as I did, and had reacted with the same distant anger. Initially it might sound absurd, but this misplaced rage is a new mutation of Jewish guilt infecting the Holocaust’s third generation. My grandparents were miserable because they genuinely felt “survivor’s guilt”. Accordingly, my baby-boomer parents inherited a good portion of this Jewish guilt because they grew up with parents who were constantly plagued by it. In recent years, however, as the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors have become adults, there has been a new development in the tradition of Jewish guilt. Whereas our grandparents felt guilty for escaping the Holocaust, we (their grandchildren) now feel so distanced from the Holocaust that—strange as it may sound—we feel guilty for not feeling guilty. The generational gap between Holocaust survivors and their grandchildren is so great that we (the grandchildren, born in the 1970’s and 80’s) do not feel connected to the cause the way our grandparents and even our parents always have. It was just too long ago, part of a different world. Yet despite this vast distance, we grandchildren still yearn to renew this bond, this passion, and for this reason was I crushed when I traveled to Poland, eager to ignite this subconscious union with my past, only to find that I felt absolutely nothing when I came face to face with the demons from “over there”. When I touched the shoes covered in my spiritual and familial blood, I eagerly anticipated feeling pain; I wanted to cry, in fact, but I was hardly even fazed. If my grandmother had touched the same shoes, she would have lost all composure and broken down instantly. The Holocaust is a hypersensitive chord for our grandparents, but not so much for us youngsters. Nonetheless, in the fight against ourselves we try to pluck this same chord by visiting the concentration camps, only to discover the terrifying possibility that (unlike our grandparents) our sensitive ‘push-here-to-cry’ button more closely resembles the occasional busted piano chord that simply will not utter a sound, no matter how often or hard it is struck. I have come to find that we do not belong to this war, nor is it in our own possession to manipulate. But regardless, we could hardly ignore our beloved storytellers. The seeds of our mutated guilt are inevitably planted when every young Jew hears his/her first story about the Holocaust, and more specifically, about how a visit to the camps will ‘change our lives and identities forever’. In fact, I hear more transformation stories about visits to Poland than about Israel. Tacitly communicated through these stories is the implication that our Jewishness is most accurately assessed by how easily tears stream from our eyes when we see the camps firsthand. After all, only an autistic Jew could withstand such devastation and not cry, right? So given that any socialized human being—to say nothing of every Jew—would feel desperately heartless after not crying at Auschwitz, it could only be considered normal to refocus our own shame on a less terrifying prospect: that the real enemy has always been and will always be the Nazi. This way, we can rest assured that evil does not treacherously reside in our own souls but rather outside our consciousness. Nor is it an accident that in the course of refocusing our rage at the Nazis do we obtain our original goal—namely, to feel reunited with our survivor grandparents. And it works. We visited the camps, and repeated the emotional process that our grandparents experienced, despite not needing to repeat it. Only after this visit could we could rightfully hate the Nazis too; we felt that we had now paid our dues, and without questioning the absurdity of such a feeling, we reactively defined ourselves in opposition to Germany just so we could feel as alive and guiltless as our ancestors must have felt on that explosive October day. We all long to fight in the name of justice, but more often do we ignore the possibility that the enemy might be buried deep inside their own souls. I am not arguing that the enemy is, in fact, buried inside us. I am merely illustrating how quickly and irrationally we reject the potential for such a possibility. I was terrified what my dry eyes meant about me as a Jew, so I covered it up with anger at the Nazis, just as many of my friends did. But we were repressing this powerful sense of guilt as though it were legitimate and deserved, as though not crying at the camps were actually a threat to our Jewishness. Yet as Svetlana and I came to see, we don’t need to feel guilty for being happy and distanced from the Holocaust; it’s what our ancestors died for. With a different lens, this disciplined inclination is equivalent to young women becoming professionals simply because they feel they owe it to their grandmothers who did not have the opportunity, and in the process vilifying men for their sexual tyranny; when the truth is that our grandmothers struggled to have the choice to be professionals. But what do Jews return to Poland for? Each of us on the trip has the freedom to live without persecution, and yet we eagerly immerse ourselves in a fight that just isn’t there anymore. I can even hear my grandparents scoffing at my desire to struggle passionately: If you are fighting something, it means that you hate where you are—it means that you immediately want to come right back home if you could, where you’re safe and healthy, where you can have kids and not worry if they’ll be ripped out of your arms tomorrow. And these voices are absolutely right. It’s all about contrast. In Poland in 2003 Svetlana and I asked, “What good is freedom if we don’t feel impassioned?” Yet in Poland sixty years ago our grandparents asked, “What good are passions if we are not free to seek them out?” But regardless of contrast, both questions ignore the reality that passion is invariably borne from struggle, from an all-consuming sense of mission. We love fighting for our goals, especially when we feel that our cosmic sense of good and evil is in great peril. Svetlana and I wanted to taste the experiences of our grandparents, but—and here’s the catch—only because we had the luxury of knowing we would not be executed. Of course we would not want to feel our grandparents’ passion if it meant we had to worry about death; but this is precisely the point. The passion was there sixty years ago because they worried about death. Quite irrationally, then, our repressed guilt has inspired us to yearn for a pleasure that can’t be defined (much less obtained) without a corresponding sense of pain, which is absurd to seek out actively. Imagine yearning for a life brimming with heartbreak but not love. Not only is it is logically impossible (because heartbreak could only be the effect of love), but even if it were possible, such a desire would seem downright masochistic. After all, pain is not the only indication that we are alive and kicking. Furthermore, it is insulting to our ancestors to yearn for their plight or take on the burdens that consumed them. They died trying to get out of Poland, and too many of us are desperately trying to return in a pathetic attempt at self-realization. Yearning for passion in this way is a childish fantasy that many people, not just Jews, have to outgrow. While Judaism is my guilt, many people seem to have something just like it—something pushing them (at best) toward self-inflicted misery and (at worse) toward the kind of displaced hatred that inspired Hitler. And yet more Jews make pilgrimages to Poland every year to renew the battle cries of a guilty generation, as though it were a healthy rite of passage akin to a bar/bat mitzvah. While I would be the first to emphasize the importance of remembering the Holocaust, there is a difference between not forgetting (which is the ostensible reason for these pilgrimages) and allowing oneself to drown in a nebulous and reactionary existence. The definition of a Jew must not be nor ever become the hatred of Nazism; short of extermination, nothing would kill the Jewish spirit with greater ease or derision. For this reason do many young Jews today feel quite lost; we join the fight against dead Nazis to assuage the spiritual solitude of living without spiritual crisis. We have no emergency by which (or against which) to define ourselves. There is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but for better or worse this does not qualify in most young Jewish minds as worthy of personal crisis-status. So we are either sustained by our continuing hatred of the Nazis, or completely lost because there is no fight we can passionately get in on. And while it is true that pleasure cannot be felt without some pain, it is a good thing that currently Jews are not feeling that pain. I feel certain in proclaiming that six million dead Jews would be pleased to hear the news. I can only hope that at some point we realize that pain is not the path that leads to happiness, much less a healthy reminder of Jewish survival. Suffering merely provides a frame of reference—or contrast—with happiness, but we mistake this for its cause. In the end, guilt is never a healthy motivation to do anything, nor should it be surreptitiously utilized to spawn hatred, invigorating though it may be. Even if founded on oceans of love, hatred is a tool for tyrants. And this planet—to say nothing of Jews—has had its fill of tyranny. I would never ask that anyone forgive the perpetrators of the Holocaust, if only because forgiving the Nazis is not necessary to live a healthy spiritual life sixty years after the fact. I am simply suggesting that we will have lost far more than six million brothers and sisters if we continue to believe that fighting is living, and living is fighting, especially when the foundation of this belief is the mutation of our happiness into guilt. Why must we hate being happy? There is nothing wrong with feeling a buffer between one’s personal sense of identity and the events that are said (by others, no less) to define that identity. The Holocaust is important and always should be, but being able to control its influence over our collective sense of self is indicative of our emotional maturity, not our heartlessness. There are a great many things in equal need of recognition, one of which is that the dead will always have unreasonable demands. And strangely, our first reaction is to love them for it. from the November 2004 Edition of the Jewish Magazine Material and Opinions in all Jewish Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish Magazine accepts no liability for material used. |

|

PAGE | | | US | | | DONATION | | | ARTICLE | | | US | | | SUBSCRIPTION | | | ARCHIVES |